La Comandante Maya: Rita Valdivia on the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Death of Che Guevara

Click here to read five poems by Rita Valdivia, never before translated into English.

October 9, 2017, will mark the fiftieth anniversary of Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s death in Bolivia. I was already an adult when that event shook the world. Following Guevara’s capture in battle the day before, his execution was ordered by the CIA and quickly carried out by a Bolivian military official in a tiny mountain village. Those who murdered him thought they were obliterating the man and what he stood for, but their act, rather than demonstrate the defeat of his ideals, made him an instant emblem of those ideals for generations to come. Fifty years later, I remember the moment as if it were yesterday.

Che’s story has been represented in hundreds of books, poems, films, songs, and images displayed on posters, T-shirts, and other ephemera. Some versions demonize, most idealize him, portraying him larger than life, devoid of any human frailty. What they all have in common is a significant erasure of those women who participated in his struggle. Only a German named Tamara Bunke, or “Tania the Guerrilla Fighter,” appears in most of those books or films, her story twisted to fit the point of view of the author or filmmaker. Historians have used that lone woman as a token representative of female participation in the Latin American armed struggle movements of the era.

Although most of Che’s comrades in his final doomed endeavor were men, many women also took part: as strategists, decoders, drivers, nurses, keepers of safe houses or liaisons in the cities, or as fighters on an equal footing with their male comrades underground and in the mountains. A few held leadership positions. Here I want to honor the names of some of the female participants in Bolivia alone, and the list is inevitably partial: Tamara Bunke, Mónica Ertl, Loyola Guzmán, Amiria Murillo, Marcela Toiti, Luxer Estática del Worpo, Josefina Fargat, Marlene Ariola, Beatríz Allende, Jhenny Coler, Amalia Rada, Loila Sánchez, Graciela Rutillo, Marina Briz, Cecilia Ávila, Rita Valdivia. In 1961 Domitila Barrios de Chungara and seventy other women founded the powerful Housewives Committee at the Siglo XX tin mine. Women were involved in student strikes and union struggles. In our gender-discriminatory version of history, most of these women’s names have been lost to memory. But in today’s Bolivia, half of all government ministers are women, a woman is president of the senate, 47 percent of all senatorial seats are held by women, and women occupy 28 percent of all congressional seats. In Evo Morales’s government, many of these women are indigenous, in other words, poor women of color. Women of the 1960s paved the way for this later participation, just as Juana Azurduy and Micaela Bastides, leaders in Bolivia’s anticolonial rebellion of 1780, set an example for them.

I can think of no more fitting tribute on this fiftieth anniversary of Che’s death than to bring to the forefront one of the women who took up his mantle: Rita Valdivia. She didn’t hesitate to participate in this centuries-long resistance against injustice that unfolds generation after generation. When Venezuelan poet José Delpino mentioned her to me recently over tapas at a restaurant in Evanston, Illinois, I was stunned. I had researched and written a book about Guevara yet had never even heard her name.[1]

Rita Valdivia, or “La Comandante Maya” as she is remembered by her revolutionary comrades, was born in Cochabamba, Bolivia, on June 20, 1946.[2] Later, her father went to Venezuela to work on building a railway line in the eastern part of the country. Her mother kept her six children in Bolivia for the next two years but eventually brought the family to join him there.

In Bolivia, Rita had gone to a Catholic primary school. Frequent childhood visits to her grandparents, who lived in the countryside, put her in touch with nature and gave her an early taste of freedom. In Venezuela, she spent important years of her adolescence and young adulthood in the city of Barcelona, state of Anzoátegui. There she studied at the Armando Reverón Art School and worked with a cultural collective called Trópico Uno. It was a time of artistic effervescence: visual artists tended to write poetry, and poets made visual art. A political awakening also characterized the young people of that time and place, largely motivated by the U.S. war in Vietnam and a growing awareness of the ways in which imperialist interests were similarly manipulating and exploiting Venezuelan youth.[3]

It was a time of artistic effervescence: visual artists tended to write poetry, and poets made visual art.

It may be difficult for people today to understand why so many young people of the 1960s and ’70s, with brilliant futures before them, chose a mode of struggle that pitted them against such superior forces. The Cuban Revolution certainly played a central role, especially in Latin America. But those young people also felt a moral imperative. The same United States that was intensifying its war in Vietnam was supporting—funding, providing weaponry and training—local forces that were oppressing their own peoples throughout the so-called third world. And it was trying to seduce them through methods that ran from sophisticated to brutal. Shortly before his death, Che had called for “two, three, many Vietnams.”[4] Youth such as Rita were intent on creating scenarios they believed would disperse imperialism’s forces and allow them to establish beachheads from which they might create spaces of social justice.

Some intellectuals, artists, and political comrades still remember Rita from this period. Poet Gustavo Pereira describes her as having had “a tender nature, contemplative rather than extremely talkative.” Photographer Marina Briz weeps as she says: “I think of her as someone striking the match of her own life; the match remains upright until it burns itself out. It was the fate of so many.”[5]

When Rita was nineteen she moved from Barcelona to Caracas, probably to escape an abusive and controlling father. There she took classes in architecture at the University of Venezuela. This led her to Europe, where she spent two and a half years studying art history at the Karl Marx University in Leipzig. It was there that she became more fully radicalized, writing in a letter to one of her poet friends back home: “Europe is dying. . . . Please don’t write to me like St. John Perse; write in your own voice.” It was in Leipzig as well that Rita was recruited by the Bolivian National Liberation Army (ELN, in its Spanish acronym).[6] There is also evidence of her having visited New York and having been in Paris during the May 1968 uprising.

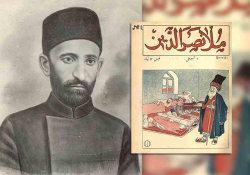

Rita was active with several vanguard Venezuelan literary groups of the 1960s, among them Tabla Redonda and La Pandilla de Lautréamont. Venezuelan poet and cultural icon Edmundo Aray says: “Rita lived in Venezuela for a few years. I knew her: a great comrade, a great combatant, a poet of immense intensity. One of the first issues of Rocinante, in the 1970s, was dedicated to Rita. It included a half-page photo, several of her poems, a poem by me, and other texts. This was more than sixty years ago; it would be difficult to find a copy today.”[7]

With some effort, Aray did find a copy of that special issue of Rocinante, filled with documents by and about Rita. One, a letter she wrote from New York City to a friend named Lucho,[8] provides clues to her early family life. It describes her father’s abuse and, more importantly, her response to that abuse. In Latin America in the mid-1960s, domestic violence wasn’t often mentioned, much less recognized as a product of a patriarchal system. From this letter, we not only get some sense of how Rita saw her father’s mistreatment of her sisters and brothers but also discover a young woman who suffered at the hands of patriarchy yet was able to extrapolate from individual behavior to show how that behavior shapes society. Here are some relevant passages from this letter:

I’m here in this city called New York. . . . I carry with me an elastic pain from what went on in my family. From here I love them all, and when I think of their hatreds, their tactics, it roils my liver. From the lips of my sisters I’ve heard the horrors my father has committed these past two years. Nevertheless, I, who belong to a violent lineage, continue to love him with a terrible compulsion. If he hadn’t tried to mess with what was intimately mine, I myself might never have discovered it. The day he tried to invade my most secret places I roared like a lion and protected them before he could consummate his dirty work. Because I care for and nourish those places, I will always be able to walk free. I imagine he attacked my siblings in the same way, but they lacked the strength to defend what was theirs. My father looks down on them, especially the boys. And he hates me—I remember his last attempt to straighten me out: I was black and blue all over but witness to the most outrageously sadistic act of a father against his rebel daughter. Later, you know, things defined themselves, and I took flight. Today he loves me and if I raise my voice he cries, gazing at me with his Altiplano eyes. I remember telling you he was like a Nazi. It’s not true, Lucho, he just wanted to impose his idea of perfection on us, wanted to make something of each of us, and that forced us to define ourselves: either we adopt that perfection that is more rational now in its assessment of life, or we escape to find our own fields.

My father is very much like Kafka’s father, and Felix—the oldest—like Kafka himself, except he doesn’t write, and therein lies his self-destruction. Chabela used to admire him, now it disconcerts me to see her passive behind a sales counter, listen to her talk about her beauty products, fashion, her marvelous boys and repugnant husband. Ana will be a fine professional: reserved, disciplined, long-suffering, but she doesn’t understand madness. Nano (Fernando, the one most like me) is strange. He loves music and revolution, but gives himself entirely to his engineering studies and to his girlfriend; what’s more he likes to walk through the streets with her on his arm, already a sign of “normalcy.” Patricia—she’s like me—I feel like screaming when I think of the terrible trials that await her. Love her without confusing her like you did me, love her please and don’t let her sleep . . .

I must keep myself as I am, inside. . . . I must think intensely of every Che and at the same time be Che. And at the same time be someone who studies a profession.[9]

Here we have the observations of a young woman acutely attuned to and understanding of human nature, eager for her siblings to free themselves from tyrannical social norms, and, above all, intent on cultivating her own deepest needs. I am curious about Rita’s relationship with her mother, unmentioned in this letter or in any other source I could find.

Like many socially conscious writers and artists of that decade, Rita was deeply moved by injustice. She was determined to fight it to the limits of her possibilities. In 1967 she traveled to Cuba, where she received intelligence and counterintelligence training. On her return to the continent—not to Venezuela, but to the country of her birth, Bolivia—she was already a pivotal figure in the ELN. This was the political organization carrying forward Che Guevara’s dream. Its leader, Inti Peredo,[10] put her in charge of the underground movement in Cochabamba. All evidence points to the fact that, despite her young age, she did an outstanding job. On the night of July 13–14, 1969, she and others were to meet at a safe house in the city; Rita herself had arranged the logistics of that gathering. When they arrived, they found themselves surrounded. Some managed to escape, but Rita and others were gunned down.

Upon learning of her daughter’s death, Rita’s mother and one of her sisters traveled to Bolivia to claim the body. Months passed. They endured a harrowing search. After a great deal of frustration, they announced in the newspaper a mass for Rita’s soul. The ELN was thus made aware of their quest. Comrades knew where the authorities had the body and helped the family recover it. Her loved ones were finally able to bury Rita.

Not surprisingly, it was difficult to come by detailed information about Rita during her time underground. But through a friend of a friend—one of those webs that seems magical, even today—I heard from a survivor who knew Rita well. He says: “Maya was her war name. She was the person responsible for us when we went to Cuba for training. I happened to be nearby the day she died. I witnessed the death of her partner and was present at her secret burial. She has a beautiful gravesite, and those of us who remember her keep it up to this day. Inti had a lot of confidence in her, and her death in combat affected him deeply.”[11]

The poems and other texts she left contain echoes of social justice themes, but their power lies in their imaginative lyricism, almost surreal at times.

Clandestine struggle tends to swallow its foot soldiers. Poetry, particularly when it rises above the ordinary, can perpetuate those who produce it. Although barely twenty-three when she died, Rita was already considered one of her adopted country’s most promising poets. It was the 1960s, and hers was a rebel voice. It was also the voice of a mature writer who, had she lived, would surely have made an even greater mark on Latin American literature. The poems and other texts she left contain echoes of social justice themes, but their power lies in their imaginative lyricism, almost surreal at times. Like the Beats in the United States, the Nadaistas in Colombia, Techo de la Ballena in Venezuela, and similar groups elsewhere, she ranted against social hypocrisy and a culture of “men in gray flannel suits.” In “Defending the Street,” she writes: “Blood escapes my hands. Humanitarian blood. Shamed blood. / Vegetable sap and the babble of hunger and boredom.”

In her personal integrity, in her social analysis, in the university studies she managed to complete, and in her position within the armed struggle organization with which she chose to act, Rita seemed larger than life, mature beyond her years. In all these arenas, she accomplished more than many who live twice or three times as long. Despite her youth, she had traveled widely, putting her in touch with other cultures and peoples. Her poetry, as I’ve said, was stunningly mature. She wasn’t the intellectual whose “political poetry” simply referenced injustice. And she wasn’t the activist who wrote an occasional poem, like Camillo Torres, Agostinho Neto, or Che himself. Considering how brief her life was, she left a body of work, reminiscent of Ho Chi Minh, Roque Dalton, Otto-René Castillo, and Javier Heraud. Her work was published in Trópico Uno, En Haa, and Rocinante—important magazines of the era—as well as in anthologies such as Bajo la refriega and 7 poemas (both 1964), En plena estación (1966), Por mi cuenta y riesgo (1967), and Mario Benedetti’s Poesia trunca (1977).

Rita’s place in struggle seems to have been no less developed. Because of her youth and gender, it would be easy to assume that the title of commander was simply a sign of respect or endearment rather than a military rank earned in battle. But we know it was, in fact, a legitimate title, bestowed on her by the ELN’s leader. Few, if any other, twenty-two- or twenty-three-year-old women could have earned it.

When following the multiple trails of a presence such as Rita’s—testimonies from those who knew her, bits and pieces of information, clues found in the work itself—I encountered in almost equal measure the life lived and the one that might have been. The first emerges as fact, the second like a sort of hologram: what might logically have come later but, because her life was cut so short, would never be. A feminist analysis long before its time indicates that, had she survived, Rita might have contributed to the understanding of patriarchy so richly explored in subsequent decades. Her brand of activism, although misguided in the opinions of many, was on the cutting edge of struggle during her last years. Seen in broader historical context, it foreshadows the important female leadership in Bolivia today and constitutes an important phase in the search for overall liberation. And Rita’s poetry, the place where she expressed her vision most concisely, remains the best testament to her commitment, brilliance, originality, and imagination.

They were students, professionals, laborers, farmers, loners, and housewives. Each committed him- or herself to a David and Goliath fight from which they knew death and anonymity were the most likely outcomes.

How many unremembered men and women took part in the social justice struggles of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s? They were students, professionals, laborers, farmers, loners, and housewives. Each committed him- or herself to a David and Goliath fight from which they knew death and anonymity were the most likely outcomes. At the very least, each sacrificed the comforts and rewards of family and everyday joys because they believed in a cause greater than themselves. Most revolutionary efforts of those years ended in failure. Hundreds, if not thousands, of martyrs have been forgotten. Remembering those times, someone who took part remarked: “If we had prevailed, streets would be named after us, statues erected. We failed, and so we are mostly forgotten.”12 The women were forgotten much more easily than the men. In today’s world of rampant violence and corruption, the ideals for which they lived and died seem impossibly utopian.

Rita Valdivia is almost unknown outside literary circles in Venezuela and Bolivia. She remains unmentioned in the books written about Guevara’s heroic gesture or its aftermath. How many other women met with a similar fate? The poems she left when she died are complex and powerful. To date they are unavailable in the United States. I have translated five of them here, in tribute to this young woman—one of many who gave their lives, the children they might have had, and poems they might have written, to a dream still begging fulfillment across the continent.

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Author note: My profound gratitude to María Gabriela Aimarete, Edmundo Aray, Rosario Barahona Michel, Elizabeth Burgos, José Delpino, Chellis Glendinning, Eduardo Jozamí, Leandro Katz, Ana Longoni, Mario Pellegrini, Roberto Tejada, Beatriz Trujillo, and an anonymous informant for information that helped me connect some of the dots in Rita’s life. And thanks to Lynne DeSilva-Johnson for always being willing to take on another challenging project and executing it as only she can.

Footnotes

[1] Che on My Mind (Duke University Press, 2013).

[2] Comandante, or commander, was the highest rank in many armed struggle movements of the 1960s and ’70s. Maya means “first” in one of the Mayan languages, but it was also the name of Rita’s best friend when she was studying in Leipzig, a young woman from Iceland.

[3] This and other observations are from the film Tributo Homenaje a Rita Valdivia: Su memoria sigue viva, by Carlos Arratia. Translations mine.

[4] From Ernesto Che Guevara’s message to the Tricontinental Conference, Havana, April 16, 1967.

[5] Tributo Homenaje a Rita Valdivia.

[6] The ELN was the armed resistance organization that took up Che’s fight after his death.

[7] Email to author, May 15, 2017. Translation mine.

[8] Luis Luksic, director of the Armando Reverón school when Rita studied there, and a longtime mentor and friend. Marina Briz believes he was the positive father figure Rita never had. Luksic gave this letter to the magazine.

[9] Translation mine.

[10] Inti Peredo assumed leadership of Che’s guerrillas after the latter’s death.

[11] Because he still lives in fear, I will not reveal the name of this witness. Translation mine.

[12] Translation mine.