Paul Celan Translating Others

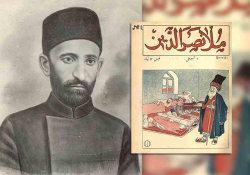

“Celan as Translator,” our huge and astonishing job here, could be taken over totally by a brilliant book sitting next to me. But Celan als Übersetzer (1997), has 623 pages of not easy German. To begin, here’s Paul Celan in middle life, with books:

Within his studies, teaching, marriage, fatherhood, readings in Germany, and writing of poetry, translations took up much of the 1950s for Celan, and again in the 1960s. Many were paid jobs, others for his own interests, sometimes for both love and money. He translated over forty poets, plus Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog documentary and other items. He translated for Geneva’s International Labour Office and set translation exercises for students at the École Normale Supérieure. During nineteen months of forced labor, he wrote poems regularly while also translating Shakespeare sonnets, Verlaine, Yeats, Housman, Éluard, Esenin, and others. From then on his favored English-language poets were Shakespeare and Dickinson.

Shakespeare

Protesting for Yiddish at thirteen, Paul asserted: “Even Shakespeare has been translated into this language!” He began learning English so as to read the Bard, tried some sonnet translations, and at eighteen went to see the plays performed in England. When the Germans invaded in 1941, he recited his Shakespeare in the Czernowitz ghetto, I’m told, and during months of forced labor he carried a notebook containing his version of sonnet 57.

In these translations, Shakespeare suffers a sea change into something rich and strange, often very strange. In sonnet 79, with genocide and eclipse in his life, the poet/lover already sounds like a zealous translator: “Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent / He robs thee of, and pays it thee again.” Then Shakespeare’s balanced phrasing,

. . . beauty doth he give,

And found it in thy cheek: he can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live,

surges with fresh emphasis in Celan’s version:

. . . Er kann dir Schönheit gehen:

sie stammt von dir — er raubte, abermals.

Er rühmt und preist: er tauchte in dein Leben.

[. . . To thee he can give beauty:

it stems from thee — he plundered, once again.

He’ll praise and prize: he plunged into thy life.]

The added thrust of “plundered, once again” and “plunged,” the doubling of “praise” and “prize,” plus Celan’s new verse breaks, all display translation’s possessive force.

Sonnet 90’s themes of betrayal and bitterness tallied with his own state of mind:

Then hate me when thou wilt, — if ever, now —

Now, while the world is bent my deeds to cross,

Mußt du mich hassen, haß mich ungesäumt,

gesell der Welt dich zu, die mir den Weg vertritt,

[Do you have to hate me, hate me without delay,

you join with the world, which replays the way for me,]

—if I have it right. In sonnet 5 a “hideous winter” drives into postwar German. Translated, it can hit and cut and break what’s happening. Where Shakespeare runs almost unbrokenly, Celan’s verse stops nine times. It’s surplus intensity. In the second stanza, when the English sonnet shifts to the present and “leads summer on / To hideous winter,” the German is already looking back: “Summer was.” Since the German for “time,” Zeit, can mean “tense” as well, the fell hand of grammar itself seems at work. Celan recasts Shakespeare’s summer in a spontaneous question and answer: Ist Sommer? Sommer war. It’s gone—with the emphatic past-tense war and Celan’s new word Schon (“Already”). As Sommer abuts Sommer, with only a question mark separating them, we hear a moment’s dialogue on time and translation: “. . . summer? Summer . . .”

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there,

Sap check’d with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnowed and bareness everywhere:

Ist Sommer? Sommer war. Schon führt die Zeit

den Wintern und Verfinsterungen entgegen.

Laub grünte, Saft stieg . . . Einstmals. Überschneit

die Schönheit. Und Entblösstes allerwegen.

[’Tis summer? Summer was. Already time

leads on to winters and to darkenings.

Leaf greened, sap rose . . . In time past. Oversnowed

is beauty. And a bareness everywhere.]

Celan drops and adds words, deflects and reshapes phrases, alters tense and number and punctuation.

Emily Dickinson

In another spirit, Celan can truly reply with close and clear translation. A century after Emily Dickinson, he shared her solitary, baffled, spiritual yearning and her sense that death dwells close and poems speak truth, if anything can. Here is a lyric whose rhythm and density Celan echoes, and then some.

Let down the bars, O Death —

The tired Flocks come in

Whose bleating ceases to repeat

Whose wandering is done —

Fort mit der Schranke, Tod!

Die Herde kommt, es kommt,

wer blökte und nun nimmer blökt,

wer nicht mehr wandert, kommt.

[Away with the bar, Death!

The Herd comes in, they come

who bleated and now never bleat,

who no more wander, come.]

Even without knowing German, we can grasp Celan’s syllables and accents: “Let down / the bars, / Oh Death — ,” Fort mit / der Schrank- / e, Tod! (Schranke has two syllables.) Then “The tire- / d Flocks / come in,” Die Her- / de kommt, / es kommt. (Herde has two syllables.) These two English and German lines have six syllables first, then a third line with eight, and the forth has six again. Perfect balance, rhythm, and sound.

A century after Emily Dickinson, Celan shared her solitary, baffled, spiritual yearning and her sense that death dwells close and poems speak truth, if anything can.

However! Look at the first line in each language. Dickinson’s “Let down the bars, O Death —” opens with that desperate wish. Celan’s line is blunt command. His Fort mit der Schranke doesn’t say “Let down . . . ” but “Off with . . .” or “Away with the bar.” And Emily’s gentle Psalm-like “O Death —” comes out in rough German: Tod! “Death!”—plus that added exclamation point. After which we hear Celan’s third kommt!

Dickinson’s second stanza opens tenderly, addressing death. This time her translator finds equivalence, pure likeness:

Thine is the stillest night

Dein ist die stillste Nacht

No need for reinventing what happens in the original. Every word is cognate, related: “Thine” = Dein, “is” = ist, “the” = die, “stillest” = stillste, “night” = Nacht. We should be so lucky. Though Dickinson’s poems are perfect, that didn’t deter Celan from translating again and again according to his axiom, “In a poem, what’s real happens!”

Thine is the stillest night,

Thine the securest fold:

Too near thou art for seeking thee,

Too tender to be told.

Dein ist die stillste Nacht,

der sichre Pferch ist dein.

Zu nah bist du, um noch gesucht,

zu sanft, genannt zu sein.

[Thine is the stillest night,

the surer fold is thine.

Too near thou art to yet be sought,

too tender, to be named.]

With every word cognate in the first line, either the English or the German could have come first. But Dickinson’s soothing parallel—“Thine . . . / Thine . . .”—is inverted by Celan, as if a translation must bear inversely on its source. Of course, the upcoming rhyme counts here, because Celan’s dein (“thine”) is moving toward sein (“to be”).

What is lost is Dickinson’s odd doubling of Death as subject and object: “Too near thou art for seeking Thee.” What is gained is the delay of sein, Celan’s final verb of being, which almost counteracts death. Just one more surprise awaits us in his closing syllables. Death for him is too tender not to be “told” but “named.” “Praise the name of the Lord,” the Psalmist says.*

Robert Frost

Celan translated over forty poets from French, Rumanian, Russian, English (both British and American), Italian, Portuguese, Hebrew. He once made a generous attempt at Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” in which his horse happens to stop on “the darkest evening of the year.” His interwoven rhyme and lucid four-beat rhythm don’t carry over, but watch.

To bring out Celan’s odd moves, we can watch its last lines. “Of easy wind and downy flake” moves easily, pleasantly through an accent or stress every two syllables: “Of ea- / sy wind / and down- / y flake.” Below is Frost’s original line, then Celan’s translation set above a strange word-for-word back translation of Celan’s version.

Of easy wind and downy flake

doch, dies noch: leichten Wind, die Flocken, erdwärts, dicht

[yet, this too: easy wind, the snowflakes, earthward, thick]

This Jewish poet-survivor, Paul Celan, whose parents perished in a 1943 Ukrainian winter, draws nine words from a six-word line. Meanwhile, he turns “downy,” which actually means “fluffy,” into “earthward,” erdwärts. Does he really think a downy flake is sweeping “down”? Perhaps. Or is he wrenching a dark German pun out of “downy” flake? That’s attempted at home. But tough translation needs radical responses.

Frost’s famous last two doubled lines:

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Und Meilen, Meilen noch vorm Schlaf.

Und Meilen Wegs noch bis zum Schlaf.

[And miles, miles yet before sleep.

And miles of road yet until sleep.]

What has become of the speaker’s “I”? Many have wondered whether Frost’s repetition embodies a death wish or its opposite, or drowsiness. Perhaps for more interest, Celan makes his own repetition, “miles, miles,” then shifts “before” to “until,” putting off sleep a shade longer.

Osip Mandelshtam

“I consider translating Mandelshtam into German to be as important a task as my own verses.” How did young Paul Antschel—later Celan—know Russian and esteem a poet destroyed under Joseph Stalin? He was born in 1920 in Czernowitz, which became part of Romania after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918. After the Hitler-Stalin pact and the outbreak of war in September 1939, Romania was ceded to the USSR, and in 1940 Russian troops occupied Czernowitz. This hobbled Paul’s studies: “Now I am a Trotskyite,” he said. Yet Soviet occupation helped his command of Russian. A teacher recited poems by the “non-person” Osip Mandelshtam, and a friend remembers Paul in 1941 already reading War and Peace in the original.

Throughout his life, Celan bought Mandelshtam’s works. In 1958 he undertook to be the “secret addressee” of his Russian predecessor and translated an elegy written in 1916 after Mandelshtam’s mother’s funeral. The Russian poem begins, then Celan translates:

[This night is not remediable,

but with you there is still light.

At the gates of Jerusalem

a black sun arose.]

Diese Nacht: nicht gutzumachen,

bei euch: Licht, trotzdem.

Sonnen, Schwarz, dir sich entfachen

vor Jerusalem.

[This night: not to be made good,

with you: Light, nonetheless.

Suns, black, that kindle

before Jerusalem.]

In these three stanzas, I offer (1) the Russian wording from various published translators; (2) Celan’s German version; (3) my translation of Celan’s.

With a colon after “This night” breaking the original verse movement, Celan takes over Mandelshtam’s elegy. Across the break in his German line is the night his own mother was taken off; nicht gutzumachen (“not to be made good”) refutes postwar Germany’s Wiedergutmachung (“making good again”), the reparations recently agreed to for Jewish survivors.

Celan could not make a move without transmuting Mandelshtam. Nonetheless, he would still respect the Russian 4/3/4/3-beat stanza: Sonnen, Schwarz, die sich entfachen / vor Jerusalem. A blunt trotzdem (“nonetheless”) rhymes with Jerusalem. Then, reversing Mandelshtam’s last two lines, Celan goes straight from “Light, nonetheless” to “Suns, black” (for the Russian “black suns”). And then Sonnen, Schwarz makes a slight shift from the original. Yet by multiplying “Suns” and giving “black” its status in the present rather than the past tense, Celan turns a symbol into a perennial presence. Or call it a creed. “May I say even here, right away, that Osip Mandelshtam lies closest to my heart?”

Did the Germans kill Mandelshtam? Celan first thought so. Later he realized that the death, a death hounded by Joseph Stalin, happened in late December 1938 in a transit camp, at the age of forty-seven.

Did the Germans kill Mandelshtam? Celan first thought so. Later he realized that the death, a death hounded by Joseph Stalin, happened in late December 1938 in a transit camp, at the age of forty-seven.

Still translating him, Celan also created a seventy-four-line German narrative, “Everything is different”:

the name Osip comes toward you, you tell him

what he already knows, he takes it, he takes it off you with hands,

you undo the arm from his shoulder, the right one, the left,

you fasten your own in their place.

At the same time Celan was teaching Rainer Maria Rilke, he was still buying new Mandelshtam editions in 1969. What’s more, since mandel itself means “almond,” Celan incorporated it into his poem Mandelnde, “Almonding one.” And just before stating his last revelation, “I have come to you in Israel because I needed to,” he clipped an article from the Paris Le Monde about Mandelshtam, this “forgotten Russian poet” who “has been very well rendered by Paul Celan.” So well rendered, Celan dedicated his Die Niemandsrose, “The No-One’s-Rose”: “In Remembrance of Osip Mandelshtam.”

It is the translator who denies their silencing and addresses his mother. Celan’s voice slows in reciting these German lines, and almost chokes on Mutter.

Inevitably, Mandelshtam’s 1916 elegy for his mother enters the charged medium of his translator’s own loss. Where the Russian poem’s closing stanza begins plainly heard,

And over my mother rang out

voices of the Israelites,

Celan’s first syllable makes the Israelites Jews, as he knows them, and then adds something new:

Judenstimmen, die nicht schwiegen,

Mutter, wie es schallt.

[Jewish voices, not gone silent,

Mother, they resound.]

It is the translator who denies their silencing and addresses his mother. Celan’s voice slows in reciting these German lines, and almost chokes on Mutter.

Celan adopted Osip Mandelshtam as a blood brother and translator. Often these versions might as well be his own verse.

In 1958, while he was bringing Mandelshtam’s Russian verse into German, Celan’s French artist wife, Gisèle Lestrange, made an etching entitled Rencontre / Begegnung (Encounter), coupling two major European tongues to signify “Encounter.” Her arrowy fragments thrust diagonally, vectors meeting and piercing each other. Also a later etching: Écho d’une terre / Echo einer Erde (Echo of an Earth).

In 1958, while he was bringing Mandelshtam’s Russian verse into German, Celan’s French artist wife, Gisèle Lestrange, made an etching entitled Rencontre / Begegnung (Encounter), coupling two major European tongues to signify “Encounter.” Her arrowy fragments thrust diagonally, vectors meeting and piercing each other. Also a later etching: Écho d’une terre / Echo einer Erde (Echo of an Earth).

When it comes wholly to Paul Celan, what he knows and says leaves us stirring. Either Shakespeare is brilliantly translated by Celan, or Celan is brilliantly creating his own unique poems.

Stanford University

* Anchor brought out a $1.45 book in 1959, Selected Poems and Letters of Emily Dickinson, which Celan bought. So I did too.