On the Untranslatability of Translation

Although the author still believes in translation as the most satisfying way “to inscribe himself on the indifferent surface of the earth,” the pay-to-play world of translating contemporary literature left him in the position of what Valery Larbaud once called translators: like beggars at the church door.

I was raised in a family and social environment in which the answer to the question “What do you do?” could only ever be answered with the job that paid your bills. To this day, whenever I read a lifestyle feature on a hip new photographer, cartoonist, choreographer, opera singer, clothing designer, etc., my automatic response is, “Cool, but that’s not how you pay the mortgage.” I’m not proud of my scoffing. But if there’s one thing my years in the cultural precariat taught me, it’s that, long term, the carefully curated creative life is only available to the well sinecured, those who inherit or marry well, or else the rare individual who consents to live his or her adult life as a pauper.

The above is both a confession of my working- and middle-class prejudices (some people obviously do make an acceptable living from their art or craft) and an explanation of why I’ve never been able to introduce myself with a plain, “I’m a translator.” There was a two- or three-year stretch when I probably wanted to. In that time I translated three books, all of reasonable length, from the Croatian, two of them by Dubravka Ugrešić. It was a messy period: the final stages of my PhD, the purgatory that inevitably follows, a couple of brief postdocs. My translations of Miljenko Jergović’s Mama Leone and Ugrešić’s Karaoke Culture and Europe in Sepia paid some bills, but it’s also true that, whenever I could, I cross-subsidized the very modest translation honoraria I received with only slightly less modest academic scholarships.

The world of literature in translation is like the Olympics. It’s pay-to-play, and, as a general rule, who spends most wins.

People involved in the transatlantic world of literature in translation are normally pretty articulate, yet apart from a distinguished translator from the Czech, I’ve never met or corresponded with one who didn’t do a fine impersonation of the three monkeys when money was in question. The point is this: just as there is an enormous difference between being a German or Norwegian writer and a Croatian or Slovak one, there’s an enormous difference between being a translator from the German or Norwegian and being a translator from the Croatian or Slovak. The world of literature in translation is like the Olympics. It’s pay-to-play, and, as a general rule, who spends most wins. To win, you need a state that finances fellowships and foundations, scholarships and subventions, consulates and cultural centers, not to mention author tours or—manna from heaven—“talks with the translator.” In short, literature in translation is a state-sponsored art. This is probably a good time to mention that, given her relationship with the state of Croatia, Dubravka Ugrešić is more or less a stateless writer.

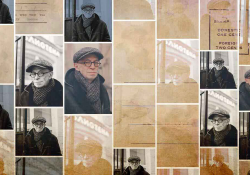

It wasn’t, however, just the money situation that inhibited me from ever introducing myself as a translator. It was equally that I just couldn’t translate to others what it meant to be a translator, let alone how I, a New Zealander with no Yugoslav roots, came to learn the language formerly known as Serbo-Croatian and translate the work of Ugrešić, one of the great living European writers. Reduced to its essence, the backstory is both fantastic and prosaic: it involves a restless young man who sought adventures on distant shores, came unstuck in a short and sad marriage, the end of which left the no-longer-so-young man searching for meaning that for a time he found in books. In New Zealand, in particular, translating all this to some dudes standing around a barbeque was pretty painful. Over time, I developed a series of useless analogies. I’d say that a translator is like the cinematographer, the author like the director. Or that the translator is like a sound engineer or producer shaping how an author “sounds.” When the dudes at the barbeque still looked puzzled, I’d just say that a translator is like a better class of wedding singer.

When the dudes at the barbeque still looked puzzled, I’d just say that a translator is like a better class of wedding singer.

As more time passed, however, it also became harder and harder to translate why I translated to those who knew me well—my parents, my partner, my siblings. Both my parents read all three of the books that I translated. Some of the stuff was hard going for them, but they took an interest and talked about the essays and stories they liked. My partner, who is Czech, was also sympathetic to the central European aesthetic in which I worked. My siblings all thanked me for the books I’d give them as Christmas presents, and I never held it against them that they never read them. At risk of coming across like an entitled brat—I deserve to live off my art!—the difficulty in translating why I translated was, in the end, inextricably linked with the financial. While the last vestiges of bourgeois decency prevent me from saying exactly how much I was paid, I can, with the benefit of recent experience, confirm that for the first couple of books it was less than what a plumber in New Zealand makes in a week, and for the third, less than what the plumber makes in a fortnight.

I forgive the reader for wondering why I’m blabbing about plumbers and why any of this matters. To me it ended up mattering because from their mid-teens until their recent retirements in their mid-sixties, my parents never had a holiday of more than a few weeks a year. My mother was a nurse and my father spent the first half of his working life as a banker (a different job then) and the second half doing physical work. Neither inherited anything. My partner is a medical secretary at a breast cancer clinic and has two children. Particularly as my siblings married, built or bought houses, prospered in their careers, no amount of nominations, awards, starred reviews, appreciations by significant literary figures, or mentions in the New Yorker could ever cut it as an adequate translation of why I translated literature. I couldn’t see it at the time, and I certainly refused to acknowledge it, but when my parents’ overeducated, thirtysomething child chooses to sell his labor well below a living wage, they can be forgiven for thinking that their blue-eyed son is engaged in a sophisticated form of self-sabotage. Likewise, a partner with a draining 9-to-5 job can, in fairness, come to think of their underemployed “artist” other half as a selfish douche.

If you can make it pay, on a good day translating literature is the most civilized of professions—up there, I imagine, with museum curator, orchestral conductor, or even ballerina, without the brutalized toes.

So why did I translate? To paraphrase a line from the first essay I ever translated for Ugrešić, it was mostly because I wanted “to inscribe myself on the indifferent surface of the earth.” (Someone somewhere is reading this and really is thinking: what a douche!) Translating Ugrešić’s work seemed my one and only shot to participate in an artistic endeavor of any significance. Most people, at least of my background, never get to sing, dance, share a studio, or make art with one of their idols, not for any sustained period of time, and not on a piece of work that matters. If you can make it pay, on a good day translating literature is the most civilized of professions—up there, I imagine, with museum curator, orchestral conductor, or even ballerina, without the brutalized toes. If I had ever ventured to describe my working day as a translator I would have liked to quote the fictional E. I. Lonoff, at whose feet Nathan Zuckerman worships in Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer: “I turn sentences around. That’s my life. I write a sentence and then I turn it around. Then I look at it and I turn it around again. Then I have lunch.” In this context, it’s not hard to understand how translating Ugrešić’s work was the best work I’ll ever do, the best “job” I’ll ever have.

It’s been just over a year now since I last translated anything for Dubravka, an essay about the refugee crisis in Europe. Before it was eventually published elsewhere online, the New York Times rejected it as not having a clear enough message for the average Times reader. That’s pretty close to the original wording. The editor might have put it differently: the essay didn’t translate. When Dubravka and I finally engaged in the dialogue confirming the end of our translation relationship, or at least our separation, it seemed as devastating as the end of a marriage. As filled with care and great tenderness as our marriage undoubtedly was, long term, it’s impossible to endure under starvation conditions.

I now earn my living as a high school English teacher. While not always a horror show, teaching is certainly a combat sport and not for the sensitive or faint-hearted. On the upside, it makes small talk around the barbeque a lot easier. Dubravka and I maintain semi-regular contact and still care deeply about what is happening in each other’s lives. I occasionally miss the days at the kitchen table turning sentences around and around. But with my working day now filled with a thousand faces (and a thousand body odors), and as I fill my little discretionary free time with less cerebral pursuits in and on water, I have the irrevocable sense that my brief life as a translator is slowly, and finally, becoming untranslatable, even to myself.

Hamilton, New Zealand