The First Twenty Years of the Twenty-First Century: Ten Reading Suggestions and a Farewell

IN 2004 I was thinking about the way that the very American style of hard-boiled or “noir” detective story has spread around the world, even to languages and literatures that had not previously exhibited much interest in crime fiction. I put some of those thoughts into an article I offered to World Literature Today and soon found myself a columnist in these pages, with too much to say, appearing in almost every issue. A lot of words by me and many more words by others have passed over my desk, so it seems appropriate to bring this marathon to a close by pointing out ten crime books that made the most impression on me since the year 2000. Adequate books are common, but the books that stick with us are the reason we read.

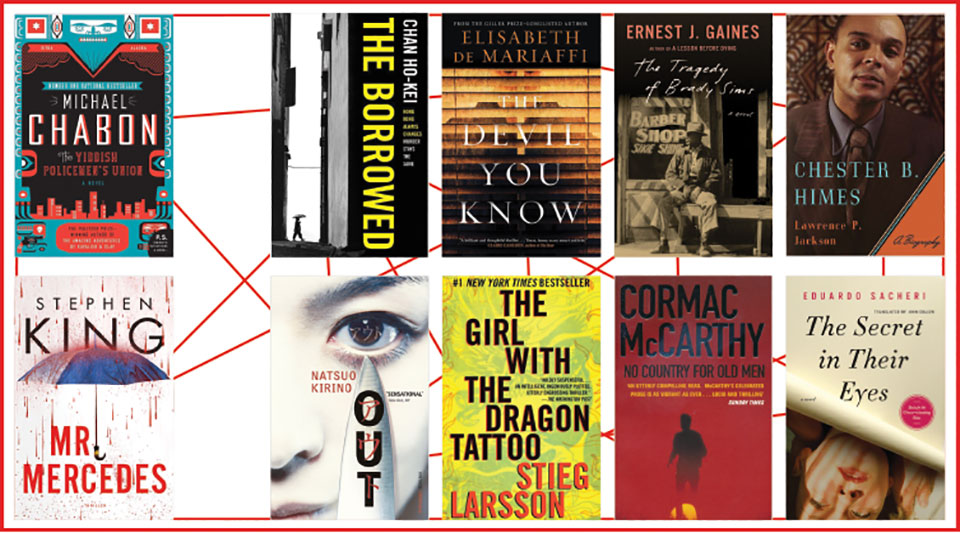

Let me start by recommending the remarkable alternative history The Yiddish Policemen’s Union (2007), by Michael Chabon. Chabon first came to literary prominence with a short-story collection, but he showed no fear in attacking contemporary literary practices, exploring the pleasures and possibilities in pop culture storytelling. He is currently a showrunner for a new television series, Star Trek: Picard, but I hope he gets back to publishing fiction soon. The Yiddish Policemen’s Union combined the tropes of the traditional hard-boiled detective novel with those of science fiction, winning him both Nebula and Hugo awards as well as top mystery award nominations. An actual suggestion made by an FDR cabinet member that the refugee Jews might be settled in Alaska caused Chabon to imagine the various settlements there and a detective trying to solve a murder. It is very unusual for a writer to pull off such a seamless union of genres, but Chabon does it.

The powerful thriller Out, by Natsuo Kirino, was published in Japan in 1997 but didn’t reach the US until 2003. A very impressive novel, it does something that I find too little of on our current bookshelves—exploring the lives of “working people.” There are too many architects, caterers, and boutique shoppers in contemporary fiction. Kirino’s main characters are women who work in a bento box factory. A bento box is rather like a TV dinner that Japanese buy in convenience stores for lunch, put together at odd hours by workers who have few social advantages. The newest employees get the worst job: spooning a blob of rice into each box for hours, until their arms ache with the repetitive motion. One of the women has an abusive husband whom she kills. Her friends, however, band together to help her dispose of the body and conceal the crime. Hitchcock, Poe, and the great story “A Jury of Her Peers,” by Susan Glaspell, all come to mind. It is a vivid portrait of the lives of the mostly forgotten people who make modern society work and of the situation of Japanese women in society.

The Secret in Their Eyes (La pregunta de sus ojos, 2005) inspired two movies: a not very good one with Julia Roberts and a Best Foreign Language Oscar one. If you have to watch the movie, watch the Argentine one, but it is better to forget them both and read the book. Written by Eduardo Sacheri, the story is of a retiring investigator who is still obsessed with a cold case he intends to write a book about: that of a young woman murdered in her bedroom. His quest for the solution is complicated by his unrequited love for an intern who has now become an eminent judge, and he soon finds himself drawn into the byzantine history of the Dirty War of the 1970s and 1980s. The military regime, backed by the US, hunted down political dissidents, “disappearing” an estimated thirty thousand victims. As you can imagine, participants in the Dirty War have no desire to have those matters revisited. A page-turner, this novel integrates the elements of a love story, mystery, and dark history in a way few novelists can manage.

I first became aware of The Tragedy of Brady Sims while reading the nominees for the 2017 Hammett Prize for Literary Excellence in Crime Writing. By the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, Ernest J. Gaines, this novella (114 pages) is powerful beyond its size, conveying most of its story through dialogue. Gaines’s novel evokes an earlier time and the culture of the men’s barbershop that has all but disappeared. While it demonstrates the racial ironies of the segregated South, the relationship between the father and the son he kills is more prominent. What makes the book truly magic, however, is the dialogue. The characters come to vivid life as they speak, and the conversation is audible in the reader’s head.

Mastery of dialogue is also a trait of writer Cormac McCarthy, and it is a rare writer who is better than he is on a bad day. No Country for Old Men (2005) should be on anyone’s top ten list for the first twenty years of this century. His characters come alive from their speech, and McCarthy needs little else to convey his story. The novel was originally written as a screenplay, which might be cited to explain why the Coen brothers made such an exceptional movie of it. As extraordinary as the film is, I find the novel even richer in creating the ambience and characters as well as presenting the dark themes of an American culture under siege much more clearly than in the film.

Toronto may be the most pleasant big city I know, but The Devil You Know (2015), by Elisabeth di Mariaffi, conjured an aura of evil in every brick. This was Mariaffi’s first novel, yet its unrelenting creepiness kept me awake. The novel is set during the time period in which serial killer Paul Bernardo and his wife, Karla Homolka, were kidnapping, raping, and murdering young girls—including Karla’s younger sister. The pall that this threw over the city of Toronto never fully lifted. Mariaffi builds her novel around a novice reporter, Evie, who is tormented by the memory of a childhood friend who disappeared in a public park. Is Evie being stalked? Did she see a man on her fire escape? Sometimes it seems she is only imagining it, that it’s some kind of survivor’s guilt for what happened to her friend. Such a disturbing psychological thriller deserves even more attention than it has received.

As an occasional reviewer, it is always a strain to be reviewing an inferior book, but to discover a talented new writer just increases the appetite for more. Hong Kong writer Chan Ho-Kei impressed me instantly with his mastery of plotting and form with The Borrowed (2017). Over four hundred pages for a crime novel loses me quickly if it doesn’t immediately prove its worth. The Borrowed is complex, weaving its storylines into a tapestry of the city and the characters’ lives. It also uses several forms of the mystery in six sections that move through significant moments in Hong Kong history and the career of master detective Kwan Chun-dok since 1967. Described this way, it may sound rather theoretical and “artsy,” but The Borrowed is as entertaining as any hefty anthology of great mystery stories and more than meaty enough for anyone wishing to confront Hong Kong’s still-evolving status from a cop’s point of view.

Many other books, of course, deserve mention, and the next two may be more familiar. Mr. Mercedes (2014), by Stephen King, showed that he has learned a lot in his prodigious output. His fifty-first novel, it was his first hard-boiled detective novel. It avoided the supernatural, used the well-worn conventions of the world-weary detective, and was nevertheless quite original. The main character is aided by several young misfits who add light humor without undermining the basic elements of the crime story. If we needed to prove that King is perhaps the master storyteller of our time, Mr. Mercedes would be on the exhibit table.

“Misfit” barely covers the psychologist’s field day called Lisbeth Salander, who assists journalist Mikael Blomkvist in perhaps the most successful thriller of the twenty-first century, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005), by Stieg Larsson. In this case, “successful” is not just commercial. I find it far superior to the sequels and better than most of its competitors. Besides the psychological dimensions of the story, I was impressed with the way Larsson employed the trope of the hermetic murder mystery, without seeming old-fashioned, confining the crime of interest to an island with a limited number of suspects. Scandinavian noir has been a tidal wave in mystery since before the turn of the century, but The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo rises above the rest.

Finally, I’d like to mention a nonfiction book, Chester B. Himes: A Biography (2017), by Lawrence P. Jackson. Himes is, to my taste, one of the great authors of crime, a writer capable of capturing the deep anger that generates most crime. Most crime novels focus on rational motivations whereas most crime, I believe, is largely spontaneous. Himes caught this—how murder can come out of a single cross word. Perhaps it was because Himes knew crime firsthand. He began writing while serving an eight-year sentence in the Ohio State Penitentiary. Like many novelists of the hard-boiled, he had to wait for serious recognition to come from Europe and lived there later in his life. No less than Walter Mosley describes Himes as “a quirky American genius.” This biography, however, makes us see the complexity of the man and reminds us to read or reread his short stories, his novel Cotton Comes to Harlem, and his other novels.

So many books, so little time! I’m nagged by the thought of so many books I haven’t included here: The Outlander, by Gil Adamson (2007), Two Days Gone, by Randall Silvis (2017). Pick one by Peter Robinson, Walter Mosley, or Margaret Atwood. Is there some way Hilary Mantel’s great Cromwell trilogy can be considered crime novels? Anne Boleyn gets beheaded, after all.

Palmyra, Virginia

Author note: I am immensely grateful that the editors and staff of World Literature Today gave me the opportunity over the past fifteen years to share my thoughts with you. I hope I’ve inspired some good reading and watching experiences. Read on! In the woods or up the alley or in the stately library, there is always another body.