Polly, Nancy, and Torchy Crack the Case: Those Relentless Women Reporters

One of the most implausible failures of realism that mystery readers generally accept is one posed by the series detectives, particularly the amateur sleuths in traditional mysteries. In novel one, Lord Fotheringale goes on holiday. A guest is murdered in the hotel, and Fotheringale unmasks the killer. In two, Fotheringale takes the train to London. An acquaintance is murdered in the next compartment. In three, he attends a dinner at stately Popham Grange, and—wouldn’t you know!—the heir of the estate is found dead in his locked bedroom. In story after story, the mere presence of Lord Fotheringale brings on murder like ragweed brings the sniffles. The amateur detective is an angel of death, and, not only that, the police even more implausibly put up with his or her meddling. The characters may grumble a bit to put a patch on it, but an amateur meddling in their work? No police force or prosecutor’s office of merit would in reality tolerate it.

Nonetheless, the Sherlock Holmes template set the pattern, even to the point of justifying the illogical meddling by making the detective an adviser to the police. Holmes is called the world’s first “consulting detective.” Cases rap on his door. S. S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance is a friend of the district attorney, and James Runcie’s Sidney Chambers is a friend of a detective inspector. Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote annoy the police but still nudge them to the crime’s solution. As the traditional detective evolves into the private eye from the late 1920s on, the gumshoe exceeds almost every legal limit on private investigation, even though in the real world, murder is strictly police business and meddling has serious legal consequences. At least the fictional premise justifies their role. In the late 1940s, the authenticity of the police procedural began to assert itself more powerfully, so presently most murder stories are set in the world of police work. Despite many errors about police procedure, they avoid the credibility issue—at least for the average reader. The legal thriller also regularly offers prosecutors and defense attorneys as investigators, which is totally credible, except to actual lawyers. Even Perry Mason pays Paul Drake to do the legwork.

Almost from the beginnings of the modern mystery, fictional reporters have been used to provide a character whose occupation can put him or her in proximity to crime, offering a motivation and compulsion to dig up the hidden facts and the pretense to knock on doors and butt into other people’s business. In a sense, Watson and the unnamed narrator of Poe’s mystery stories function like reporters with exclusive access to Holmes and Dupin. Gaston Leroux, most famous for The Phantom of the Opera, was one of the French pioneers of the mystery and exploited his experience as a correspondent. Among other stories, he covered the 1905 Russian Revolution. When he turned to fiction, he created the eighteen-year-old reporter Joseph Rouletabille to solve Le mystère de la chambre jaune (1907; The Mystery of the Yellow Room) and continued with Rouletabille stories until 1922.

Almost from the beginnings of the modern mystery, fictional reporters have been used to provide a character whose occupation can put him or her in proximity to crime, offering a motivation and compulsion to dig up the hidden facts and the pretense to knock on doors and butt into other people’s business. In a sense, Watson and the unnamed narrator of Poe’s mystery stories function like reporters with exclusive access to Holmes and Dupin. Gaston Leroux, most famous for The Phantom of the Opera, was one of the French pioneers of the mystery and exploited his experience as a correspondent. Among other stories, he covered the 1905 Russian Revolution. When he turned to fiction, he created the eighteen-year-old reporter Joseph Rouletabille to solve Le mystère de la chambre jaune (1907; The Mystery of the Yellow Room) and continued with Rouletabille stories until 1922.

The device of using women reporters as detectives appeared early in the rise of the mystery as well. Journalism was relatively open to women, compared to most other professions in the late nineteenth century. The first municipal female detective in New York City (and possibly the world) wasn’t hired until 1912, but reporters, particularly the legendary Nellie Bly, became the inspiration for dozens of fictional female sleuths. The fantasy of an exciting, independent life must have been almost breathtaking to many women in the decades leading up to the Roaring Twenties. Nellie Bly first came to national fame in 1887 by feigning insanity to get the inside story on New York lunatic asylums. In 1889 she circled the globe alone in fewer than eighty days and did many other stunts that polite girls just didn’t do. The “girl reporter” had become a figure of adventure.

Almost from the beginnings of the modern mystery, fictional reporters have been used to provide a character whose occupation can put him or her in proximity to crime, offering a motivation and compulsion to dig up the hidden facts and the pretense to knock on doors and butt into other people’s business.

Baroness Orczy, most known today for having written The Scarlet Pimpernel, began a series of mystery stories in 1901 featuring an unnamed armchair detective who irascibly deduces the solutions to difficult crimes in a London tea shop. In the first story, he sits uninvited at the table of Mary “Polly” Burton, is described as “a personality” and a “member of that illustrious and world-famed organization known as the British Press,” and explains a crime that has—you guessed it—baffled the police. In the stories that follow, Polly returns to hear the solutions to more baffling crimes and serves as his “Watson” in her newspaper. These “Old Man” stories are unusual for a number of reasons. There is no action portrayed other than that described in the crime summaries. No one is ever prosecuted, and the identity of the old man is never revealed. In the last story, the reader discovers that the old man may be a master criminal himself. Nonetheless, the stories were popular, and Polly, in her small way, opens the door for a parade of “plucky girl reporters.”

Immediately one thinks how easy it was to add some romantic spice to Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s 1928 play The Front Page by casting the male character of Hildy Johnson with Rosalind Russell in the 1940 adaptation, His Girl Friday. By then, the wisecracking female reporter was old hat in crime stories. Edward Stratemeyer, who created the Hardy Boys, Tom Swift, and the Bobbsey Twins, had a nose for pleasing young readers and invented Nancy Drew in 1930. Initially, she simply stumbled into mysteries, but by 1938, Nancy Drew: Detective appeared in movie theaters. Also in 1938, the assertive Lois Lane appears in the Action Comics #1, the debut of Superman, before many of the other repeating characters. Clark Kent and Lois work at the Cleveland Evening News, later to become the Daily Star and then the Daily Planet. Popular enough to rate a comic strip of her own (Lois Lane, Girl Reporter) in the 1940s, she continues to appear to this day in books, movies, and television, with her character (like Nancy Drew’s) adjusted to changing tastes. Her creators said she was inspired by Nellie Bly and an almost-forgotten fictional character, Torchy Blane.

Torchy Blane was a creation of Hollywood but was hugely popular before World War II. Frederick Nebel (1903–67), a friend of Dashiell Hammett and a very productive pulp writer, indirectly created Torchy in a short story in Black Mask in 1928. He wrote only three novels in his career but published hundreds of stories until 1962. As a young man, Nebel took a job in Canada on a farm. The wilderness inspired him to write adventure stories, but he soon became one of the pioneers of hard-boiled noir. He created a detective, Captain Steve MacBride, with a drunkard newspaper friend, Kennedy. Warner Brothers, which had evolved into the studio of edgy crime stories, bought the rights, and, as Hollywood does, made one small change, turning Kennedy into the best reporter in the city, a sexy, wisecracking blonde in love with MacBride, Torchy Blane. Nebel didn’t care, as long as he didn’t have to write for the movies. He took the money and had nothing to do with the movie series that followed.

Torchy’s career on radio and screen began in 1937. The first film was Smart Blonde, soon followed by Adventurous Blonde, Fly Away Baby, and Blondes at Work. Torchy was now a B-movie franchise, so the producers abandoned the “blonde” theme and put Torchy’s name in the titles: Torchy Blane in Panama, Torchy Gets Her Man, Torchy Blane in Chinatown, Torchy Runs for Mayor, and Torchy Plays with Dynamite. Glenda Farrell (born in Enid, Oklahoma) starred in all but two of these, paired with the gruff Barton MacLane as MacBride. Farrell had prime credentials in crime films, having already appeared in Little Caesar and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, but grew tired of playing newspaper women and moved on to other projects to varying success. Lola Lane (whose name was the inspiration for “Lois Lane”) replaced Farrell in one film, and the series ended in 1939, starring Jane Wyman (Ronald Reagan’s first wife) as World War II erupted.

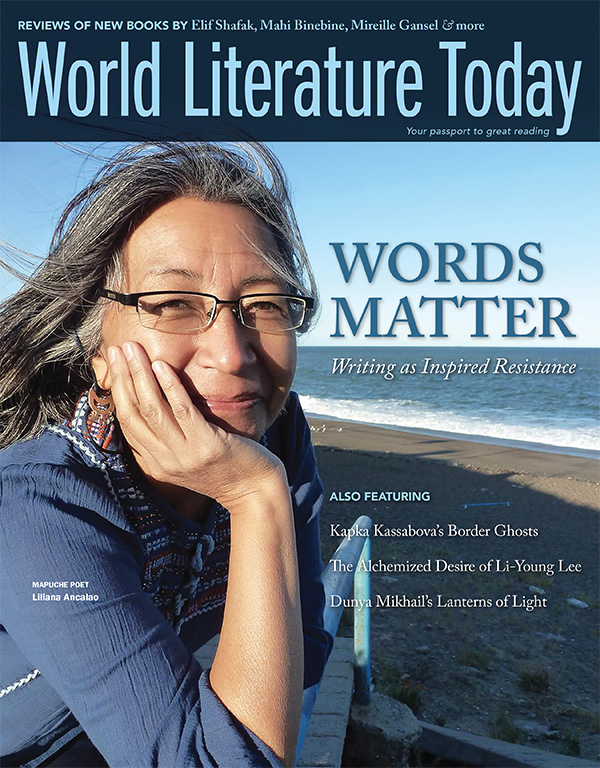

After the war, the wisecracking, plucky girl reporter might have begun to seem quaint, but the character proved as persistent as she was in the stories. There is certainly no loss of women reporters solving mysteries, right up to the present. Detecting Women 2 (1996), a directory of female detectives created by women authors, lists thirty-four newspaper reporter series and four “one-offs,” mostly of the 1980s and 1990s, not counting the radio, television, magazine, and photographic journalists. Nothing has changed in the last twenty years except the addition of a few blogging detectives. The character type has gone international, and the examples are legion. The late Alison Gordon was the first woman reporter assigned to travel with a professional sports team and covered the Toronto Blue Jays. As she often said, glamorous this testosterone-charged life on the road was not, but she melded the techniques of reporting with her insider’s knowledge of baseball into a series of mysteries with reporter Kate Henry as the detective. Eminent British author Val McDermid worked as a journalist after attending Oxford, creating lesbian journalist and activist Lindsay Gordon and winning many awards. Swedish journalist Liza Marklund became a phenomenal best-seller in all five Nordic countries with the debut of the Annika Bengtzon series. Bengtzon covers crime for a tabloid and struggles to balance her professional work with her relationships with her husband and two children. The first in the series, Sprängaren (1998; The Bomber) is considered one of the first Swedish commercial successes by a woman author, an idea that seems odd given the popularity of Scandinavian noir today. With dual English and Australian citizenship, Colin Cotterill lives in Thailand and is one of the few men to create a female crime reporter as a main character for a series. His journalist detective, Jimm Juree, has come home to a rural area of Thailand to care for her mother but, of course, stumbles into murder.

Wherever they are, whatever details differ, these relentless women push their way to the facts in story after story, often inspiring their readers to paddle harder against the societal current.

Palmyra, Virginia