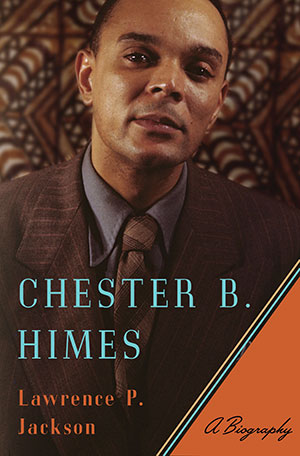

Chester B. Himes: A New Biography Reminds Us of One of the Greatest American Crime Writers

I have reservations about the value of writers’ biographies in appreciating their writings, so when a remarkable one appears, like Lawrence P. Jackson’s recent biography of crime writer Chester B. Himes, I especially hold it in high regard. Just as a book shouldn’t be judged by its cover, neither should a text be judged by the facts of its author’s life. Obscurities in a text may be illuminated by knowledge of an author’s history, but these details often make us oversimplify the underlying power in a manuscript. Peeling the layers of meaning in Hamlet would seem to be enhanced by the fact that Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, died in 1596, and the play appears to have been written about 1601. However, the more we know about an author’s life, the more we are tempted to explain the writings with reference to some historical fact rather than to an appreciation of the works themselves. This thing comes from that event, and we often think no further, though the power of writing is in its suggestions.

There are haunting resonances in an author’s pages that are always elusive. Writers write to understand what disturbs them, and they often say they don’t know what they are doing. They are listening to the Muse, they say. They are enchanted by an unfamiliar woman’s laugh but don’t know why. Something powerful is felt, and they try to capture it. If their words are successful, not even they know why the inspiring thing inspires or what all the implications are of the underlying complexities in the presentation.

There are haunting resonances in an author’s pages that are always elusive. Writers write to understand what disturbs them, and they often say they don’t know what they are doing. They are listening to the Muse, they say. They are enchanted by an unfamiliar woman’s laugh but don’t know why. Something powerful is felt, and they try to capture it. If their words are successful, not even they know why the inspiring thing inspires or what all the implications are of the underlying complexities in the presentation.

With this in mind, I find most biographies of authors oversimplify in order to support a coherent theory of the essence of its subject, as if loonies who adopt the peculiar attitude that the world is waiting for their fictions can be explained by the vicissitudes of growing up in a dysfunctional family. It can be hard for a reader to shake off the attraction of such simplifications, especially if we read the biography first and then read the works themselves through the tinted glass of a theory. I’m glad I don’t know more about Shakespeare’s personal life. I might have read him in a way that turned him into a historical artifact.

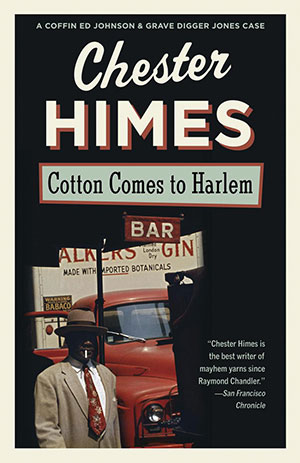

Lawrence P. Jackson’s biography of Chester Himes illuminates the life of the author and his internal struggles without grinding away the many facets. Himes is one of the most underrated crime writers of his time and ours. Despite never having lived in Harlem, he is known most for Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965). Himes was a productive novelist from his first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945), to A Case of Rape (1980). His unfinished novel, Plan B, was published in 1993, nine years after he passed away from Parkinson’s disease. If Cotton Comes to Harlem had not been made into a 1970 motion picture starring Raymond St. Jacques and Godfrey Cambridge, provoking a sequel in 1972 (Come Back, Charleston Blue), Himes might be even less known, despite a unique talent that should place him among the giants of hardboiled fiction, like Chandler and Hammett. Like Jim Thompson (and possibly even Poe), Himes was another of those powerful American authors first acclaimed as important by French readers and critics.

Writers write to understand what disturbs them, and they often say they don’t know what they are doing. They are listening to the Muse, they say.

Himes had an unusually interesting life, and Jackson’s well-written biography illuminates the complexity of the man, mostly leaving interpretation up to the reader. There’s nothing romantic about writers from the “school of hard knocks.” There’s nothing romantic about toughing through racial discrimination in all its forms, a stressful personal life, and the venal cloddishness found too frequently in the publishing industry. There was no happy ending as a stroke made him infirm in the final days of his life, and he thought of his 1976 autobiography, My Life of Absurdity, as a literary failure. He wanted to end his days in California, but a recession ruined the sale of his house in Spain. He passed away there in November 1984 without knowing that his critical and popular reputations were on the rise.

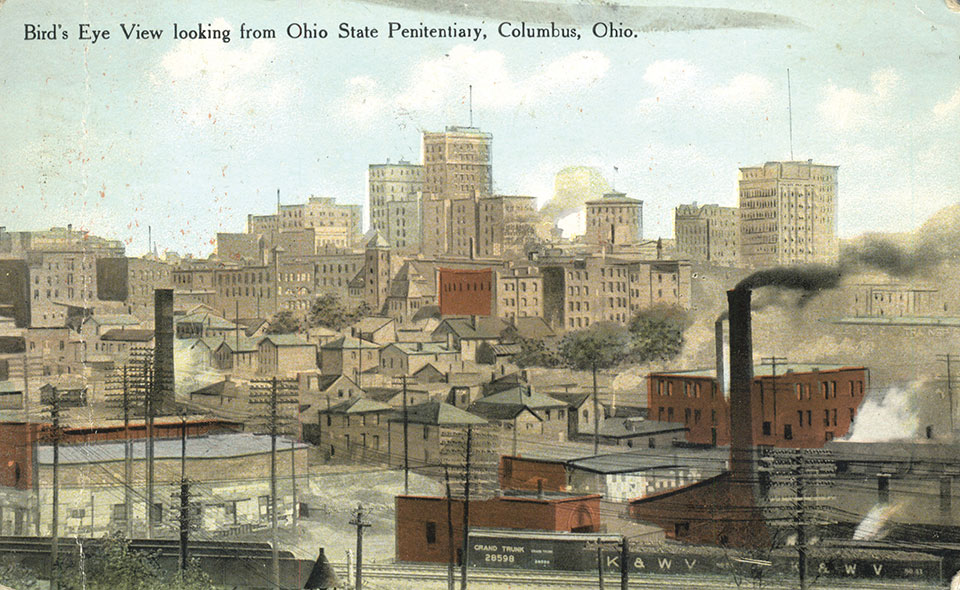

Himes began writing in prison. Born in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909, he grew up in a middle-class home. His father was a professor of industrial trades, but the marriage was a troubled one that ended in an ugly divorce. After the family moved to Cleveland, Chester mixed in Mafia circles and picked up a taste for drink, gambling, prostitution, con games, and other vices, largely financed by a worker’s compensation allowance he was granted after a two-story tumble down an elevator shaft. He entered Ohio State University but was soon expelled. In 1928 he was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to twenty to twenty-five years. There, in the same prison that once held O. Henry, he developed the strange notion of wanting to make a career as a professional writer. He read everything available, from Omar Khayyam to The Sun Also Rises, and bought a typewriter with some gambling winnings. Because of the back injury from his fall, he was allowed to write in his cell, sheltering him from much of the prison violence, though he was forever tormented by the horror of the Ohio Penitentiary fire in 1930. His short stories first appeared in 1931. By 1934 he had published prison stories with white main characters in Esquire. In 1936 he was paroled, networked with a helpful Langston Hughes, and in the 1940s worked for Warner Brothers until Jack Warner announced he didn’t want any n—s on his lot. In the 1950s Himes joined up with expatriates Richard Wright and James Baldwin in Europe, fleeing an America he could no longer stomach.

Himes began writing in prison. Born in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909, he grew up in a middle-class home. His father was a professor of industrial trades, but the marriage was a troubled one that ended in an ugly divorce. After the family moved to Cleveland, Chester mixed in Mafia circles and picked up a taste for drink, gambling, prostitution, con games, and other vices, largely financed by a worker’s compensation allowance he was granted after a two-story tumble down an elevator shaft. He entered Ohio State University but was soon expelled. In 1928 he was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to twenty to twenty-five years. There, in the same prison that once held O. Henry, he developed the strange notion of wanting to make a career as a professional writer. He read everything available, from Omar Khayyam to The Sun Also Rises, and bought a typewriter with some gambling winnings. Because of the back injury from his fall, he was allowed to write in his cell, sheltering him from much of the prison violence, though he was forever tormented by the horror of the Ohio Penitentiary fire in 1930. His short stories first appeared in 1931. By 1934 he had published prison stories with white main characters in Esquire. In 1936 he was paroled, networked with a helpful Langston Hughes, and in the 1940s worked for Warner Brothers until Jack Warner announced he didn’t want any n—s on his lot. In the 1950s Himes joined up with expatriates Richard Wright and James Baldwin in Europe, fleeing an America he could no longer stomach.

The pervasiveness of racism was never lost on Chester Himes. How could it be? An Arkansas hospital refused to treat his brother when he had been blinded by an accidental explosion. On the streets of Los Angeles, his wife was regularly propositioned by white men in cars who assumed a black woman walking down the street was a prostitute. In London, he tried to rent a flat and found the discrimination was as bad as in the Deep South. Even more galling perhaps was the patronizing of publishers and critics who congratulated themselves on their racial openness. Black writers were pressured to conform to white, albeit sympathetic, notions of them. Their fictional characters were not to be really representative of humanity but of political concepts. They were to be symbols of their race: martyrs and victims of an unjust society. It was deeply condescending, much too much for a man like Himes. The ordinary range of characterization allowed to white writers (black writers were told) was not what book buyers wanted to read in black authors. Himes was constantly urged to tone his books down in order to get them published. Readers would be upset by overtly violent black characters, especially if the anger appeared to have a sexual element. In a time when lynching was common, a sympathetic publisher would hardly wish to present angry, sexually powerful black men that racists could point to as confirming their stereotypes, yet this self-censorship cripples any writer who values verisimilitude in fiction.

No author better turns that visceral, protean anger into a graspable representation than Chester Himes. He doesn’t make it understandable—he doesn’t understand all of it himself. Yet he makes a reader feel it.

What to me makes Himes most remarkable as a writer is in that very anger which stems from all his best work. Anger is the justifiable reaction to the betrayals, torture, and killings that African Americans have endured in their history. They were slaves, they were promised freedom and social justice, and then the promises were broken. The anger is visceral, always bubbling under the surface. It erupts in larger contexts like the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. or the shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, and in smaller contexts in individual transactions in schools, restaurants, and bars. Yet no author better turns that visceral, protean anger into a graspable representation than Chester Himes. He doesn’t make it understandable—he doesn’t understand all of it himself. Yet he makes a reader feel it. He goes beyond the intellectual reaction to injustice often found in other authors and reveals the universal power of an anger that might smolder in any person disregarded as fully human. It is ferocious and frightening on his pages.

A great example is his story “Tang.” It stayed in my mind for months after I read it the first time, and I later chose it for the anthology I edited with Donald Westlake, Murderous Schemes (1996). The story is distinctive even among all the “greats” of mystery we chose, and very disturbing as the characters’ words of revolution melt into a murderous expression of pure anger. His own favorite novel, The End of a Primitive (1955), is similarly disturbing, showing a black man in an interracial relationship moving inexorably, but not consciously, toward murder. The main character in Himes’s first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go, boils with what Jackson calls the “libidinal underside of prejudice,” but Doubleday made Himes back off, so that the desire in the manuscript by the main character to punish a white woman by rape was obscured.

A great example is his story “Tang.” It stayed in my mind for months after I read it the first time, and I later chose it for the anthology I edited with Donald Westlake, Murderous Schemes (1996). The story is distinctive even among all the “greats” of mystery we chose, and very disturbing as the characters’ words of revolution melt into a murderous expression of pure anger. His own favorite novel, The End of a Primitive (1955), is similarly disturbing, showing a black man in an interracial relationship moving inexorably, but not consciously, toward murder. The main character in Himes’s first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go, boils with what Jackson calls the “libidinal underside of prejudice,” but Doubleday made Himes back off, so that the desire in the manuscript by the main character to punish a white woman by rape was obscured.Edgar Allan Poe may be vague about the reasons his mad narrators come to murder, but he is always clear that his madmen have their own mad reasons. Inheritances and revenge serve as justification in legions of stories since Poe’s. Mostly these motivations are what Alfred Hitchcock called the MacGuffin, an explanation for the struggle but not really of interest in itself—like the uranium in Notorious, or the stolen payroll in Psycho. The self-justifying rationality that is so much a part of more traditional mysteries is much less visible in Himes. Himes uses MacGuffins, like the bale of cotton in Cotton Comes to Harlem, but he stands apart in portraying the instinctive psychological and sociological motivations to crime. In this way, he is the inheritor of the determinism of Zola and Frank Norris. Brewed out of a lifetime of humiliation, of constant denigration, the rage in his protagonists catches fire and incinerates everything around them. The anger smolders and then explodes, as it does in the bars, bedrooms, and streets of our world.

Palmyra, Virginia