Two Poems from Shadow and Light: Part of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here Project

Shadow and Light was instigated by San Francisco Bay Area poet and activist Beau Beausoleil as part of a recent ancillary project of Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here (to learn more about this project, see WLT, Sept. 2013, 72). Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here began as a response to the bombing that occurred on March 5, 2007, in the street of the booksellers in Baghdad, Iraq. He was compelled to respond to this horrific bombing; it began as a reading at the San Francisco Public Library where I first met Beau and asked to be a part of this project. Beausoleil saw the bombing as an assault on ideas, on books, on free speech, and on the very idea of culture itself; at the time, he himself was a San Francisco bookseller, and it felt close to him.

Since 2007 Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here has grown from a series of readings to an edited volume of poems, a book exhibit, a collection of broadsides, and annual readings around the world to commemorate the Al-Mutanabbi Street bombing. Shadow and Light specifically memorializes the lives of academics, teachers, and educators who were killed in targeted assassinations between 2003 and 2013, a time frame roughly paralleling the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq. Those who have contributed to Shadow and Light are writers, photographers, and poets from all over the world who select the name of an assassinated Iraqi academic from a list of 324 murdered academics compiled by a Spanish NGO, take a picture, and respond to the photo and the information about the person who was killed. Beau has specifically asked those connected to Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here to participate in this open project, but Beausoleil wants as many others, who wish to, to participate in these acts of solidarity and witnessing. “Honoring the lives of those who were killed for the simple act of teaching/educating is an impossible task—that is why we must attempt to do it again and again,” writes Beausoleil in his many emails of invitation to respond to the call.

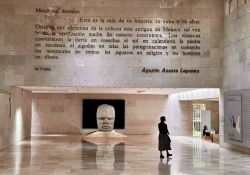

During their lifetimes, the men and women memorialized in Shadow and Light enriched diverse fields of knowledge—from history to calligraphy to the study of bees. Each assassination represented an attack on the underlying principle of education—to share knowledge—and served as a threat to scholars throughout Iraq that they were at risk. Estimates of the total number slain is about seven-hundred-plus individuals. Some of their names are still unknown, and many died with little information recorded about them. In a statement, the 2021 UC Santa Barbara online exhibition describes Shadow and Light as operating “as both a collective and artistic response but also constitut[ing] an archive, as both a testament to the lives of Iraqis and of international solidarity.” Those who respond to the accompanying photographs they submit convey stories and bits of information pieced together from news sources about each person’s life and death. To date, there are more than sixty contributors to Shadow and Light artists’ books. Readings have been held in San Francisco (2022), UC Santa Barbara (2021), and London (2021); forthcoming readings from Shadow and Light will be held at London’s P21 Gallery, the University of Iowa, University of Pennsylvania, University of Michigan, and University of Illinois in 2023.

This project is still open, and Beau Beausoleil invites others to write to him to participate and receive the guidelines. You can email him at [email protected]. One needn’t be a professional photographer to join. What follows are my contributions of photos and poems about a wife and husband, both law professors in Mosul, who were murdered on two separate occasions between 2004 and 2005.

In the Time of Cherries

by Persis Karim

This is your name, not just your death, the day

someone gunned you down at the broken

stone gates in the time of cherries.

I know you Leila, just enough to know

you live in those others who sat in rapt

attention in your classroom, the women

who believe in justice, in words and sentences

for those without a voice or any chance

of speaking. How they listened to you

extol those large truths, the way an idea starts

in the heart, then springs into the throat,

and one day becomes the law or even

just the principle of it—a flower that blooms

in the minds of 10,000 more and doesn’t

know the end of a season.

Leila, Leila, I want to say your name.

I know you were more important than this

singular caption of murder. Where do I find

your story, your hopes and dreams in the lexicon

of war? Like me, you might have liked poetry and

wanted to learn the names of trees and birds.

Like mine, your mother must have been proud.

She must have told everyone in the village,

“My daughter, she attends university

and will soon become a doctor in law.”

You came from the quiet countryside

where she and your grandmother were born

and died, but you were taken before both of them

in the big city, holding a bag of your students’

papers, and the letter you penned to your faculty

the night before warning them to be

vigilant and guard their safety

even in the lull of early summer.

Artist’s Statement

“In the Time of Cherries”

180. Leila [or Lyla] Abdu Allah al-Saad: PhD in law, dean of Mosul University’s College of Law. Assassinated June 22, 2004.

I HAVE BEEN thinking about how few women were on this list, and I wanted to connect with an Iraqi woman academic and professor. I saw Leila’s name, and I wondered what it took to become a dean of the College of Law. She must have worked hard, sacrificed things—she must have believed in the law, even when others were cynical and angry at the system, or already frustrated with the law and politics even before the US occupation. I thought of how women teachers inspire others—particularly women students. I even did a search for Leila’s name, hoping to find something about her—where she was born, what her passions were, what, if anything, she wrote about. The caption above is all I found. As we endured Covid-19, I thought about how the idea of shelter-in-place wasn’t likely possible for Leila or her colleagues or students. Iraqis worked even if they didn’t get paid; they worked for their students, despite the occupation and violence. They had to show up for them. They wanted to believe that things would get better and that something worthwhile and transformative might follow such a major historical event as an occupation by the US. I imagined her knowing her life might be in danger, but showing up for her students and her colleagues might have given her hope and a sense of purpose. And I have also been thinking about flowers and the way each tree, plant, or bush, comes into its flowering at a particular time of the year. This is a photograph of the ornamental cherry tree in my backyard. I thought of Leila today. How she was not able to fulfill her destiny and how the season of her life was cut short, but how her life, I am certain, had an impact on her students. I want to say her name, so that she will not be forgotten. So that she will continue to bloom.

– Persis Karim

I want to say her name, so that she will not be forgotten. So that she will continue to bloom.

When We Dead Awaken

by Persis Karim

She will not awaken, will not

come back to life. I thought that I could

carry on, would carry on her legacy.

I knew I would never be half the lawyer,

half the teacher she was, but I thought

I could carry on, keep her memory alive.

I would ask the same questions, meet

the same silences, get the same look

that conveyed a deadly warning.

But what was her death if I did not ask?

What was my freedom if I did not question?

I waited for the taxi to take me home.

I stood waiting in the twilight

beside the gate where she was shot. I

wept quietly in the darkness for Leila.

Her memory awakened in me that last

conversation about having children.

I stood waiting and felt her near me

as if in a dream. But neither she

nor I would awaken from this nightmare

of our country, our city, our lives. I waited

and the time passed. One minute, one hour.

I do not know how much time passed

before I clutched my chest and sucked

in the air as I fell to my knees.

It was not my heartbreak, not my weak

heart, but a bullet piercing my chest. The sky

was a violet blue and the crescent moon

hung over me, but no one knows when I,

the husband of the dean of the College of Law,

fell to his death on an unspecified date

and time on the cool cement not far

from where her blood was spilled

in the weeks or months—or was it

a whole year?—earlier.

When we dead awaken, you will know

those details. For now, I am one

of those who lives in the shadow

of the unmarked days of death when

I tried to awaken my country.

Artist’s Statement

“When We Dead Awaken”

183. Muneer al-Khiero: PhD in law and lecturer in the College of Law, Mosul University. Married to Dr. Leila Abdu Allah al-Saad, also assassinated. Date unknown.

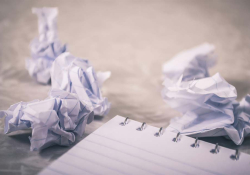

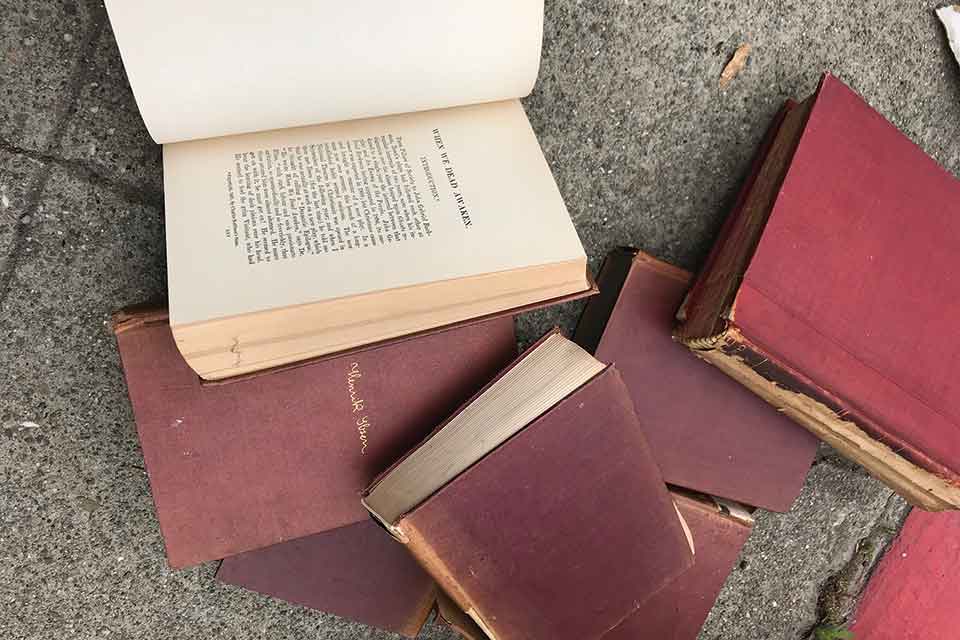

I WROTE THE first poem for Leila, “In the Time of Cherries,” and after I finished it and sent a draft to Beau Beausoleil, he asked me to consider writing a second poem for her husband (also listed) in the Mosul section. I immediately said yes. I was struck by how much less information there was about him. Not even an exact date of his assassination. I was troubled by this.

The next morning, while out walking, I encountered a stack of books that had clearly been put on the curb for any takers. They were old, slightly beat-up editions of a collection of Henrik Ibsen plays. They had been taken out of the box, and clearly someone had handled them before I found them. One of the books was open to the page that introduced the play When We Dead Awaken. It hit me, then, that this would become my picture and it would also be the inspiration for the poem I would write.

It hit me, then, that Ibsen’s book would become my picture and When We Dead Awaken would also be the inspiration for the poem I would write.

The play features a character named Professor Rubek and his wife, Maia. I knew immediately that this book opened to that page was meant to be mine, and even though I thought I should not be picking up someone’s stray books in the time of a pandemic, I took it home with me. And this is the photograph that accompanies the poem for Muneer al-Khiero, the husband of Dr. Leila Abdu Allah al-Saad. – Persis Karim

Read Beau Beausoleil’s poem “Regarding the List of 324 Iraqi Academics Assassinated.”