Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris

Farmington, Maine. Alice James Books. 2023. 100 pages.

Farmington, Maine. Alice James Books. 2023. 100 pages.

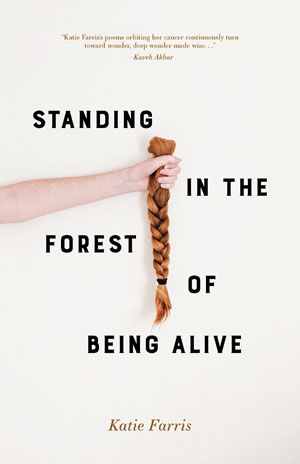

A foot of fiery red hair chopped from the poet’s head, a hand curled around the braid—this cover image is the initial offering of Katie Farris’s poetry collection, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive. Subtitled “A Memoir in Poems,” the book probes the tension between giving, taking, and theft. Holding no marvel loosely, Farris moves with defiance and dolor through the mystery of breast cancer, literary lineage, love, partnership, and poetry. Opening with an ars poetica, “Why Write Love Poetry in a Burning World,” Farris answers the titular question in the closing couplet: “To train myself, in the midst of a burning world / to offer poems of love to a burning world.”

The breast cancer diagnosis, delivered in a blunt phone message days prior to the poet’s thirty-sixth birthday, is unbelievably ordinary, as Farris conveys in “Tell It Slant,” which begins in the slant rhyme of “You float in the MRI gloam.” The spirit of Emily Dickinson stalks the stanzas in the slant, in the shorn lines, in the elliptical dashes, in the gestural work done by punctuation, in the abrupt turns and archaic diction, and in the poems that nominate her presence. Sitting in the oncology waiting room, Farris addresses Dickinson: “I meet / your sweet velocity in every / thing that flies—”

“I return to this point of wonder:” the speaker tells us in the first line of “Outside Atlanta Cancer Care,” a staggering poem punctuated with Dickinsonian dashes. The wonder of it all is that the unbelievable can happen, that we can live without realizing how life is divided by the knowledge of diagnosis. Farris asks us to witness this—to live in the space of mystery and terror sharpened by love for her husband, and love for the world. All routes include Ilya Kaminsky, Farris’s longtime partner and fellow poet. Many of these poems were initially published in Farris’s A Net to Catch My Body in Its Weaving, winner of the 2021 Chad Walsh Chapbook prize from Beloit Poetry Journal. The chapbook’s title comes from the closing lines of “In the Event of My Death,” a poem addressed to Farris’s husband as a sort of last will and testament. Midway through this moving poem, Farris turns, saying: “Promise you will find my heavy braid / and bury it—” By ending this midway stanza with an open dash, the rupture ripples throughout the poem.

Sutured with love, each poem careens toward the beloved. In “A Row of Rows,” intellectual ardor emerges in a dispute over whether Walt Whitman (his view) or Emily Dickinson (her view) is the “greatest epic poet”—an argument Farris takes up in the slant of this book, in the sharp lines and hairpin curves of line breaks, and in the Whitmanesque anaphora of her political poems. But the porch is the stage where love fights over lecture rights.

Seductress of the unspeakable, Farris approaches cancer and eros in the same breath. Stripped bare, exiled from her own flesh, confrontational in her resistance to shame, the poet is shameless. “Rachel’s Chair” uses an object to reflect on the freedom of sex in a careless body, in the before-cancer when so much remains undetermined. The poem opens with a memory (“Once, many / years ago, we made / love at a friend’s / house”) and then turns into a reflection on the chair they used as a site for sex. Farris’s defiance embraces the imperfection of bodies that offer indescribable pleasure and unfathomable pain.

Metaphor becomes a weapon, a strategy of insubordination to reduce the power of cancer over the mind. The symptoms of treatment make the poet visible to strangers who identify the patient with the disease rather than the individual life and person. Farris alludes to this sense of overexposure in “After the Mastectomy,” where the person of “Cancer Patient” becomes public. To lose one’s hair is to be stripped of protection (“how can a watchtower hide?”). Crossing the page in brisk couplets, the poem ends with “my bald head the beacon the first” before breaking the pattern to leave the final word, “alarm,” alone, abandoned to its own stanza.

In “Emiloma: A Riddle & an Answer,” Farris creates a sort of poetic form that plays on the cross between Emily Dickinson and a carcinoma. Echo emerges as the shape of fidelity, a remembered presence. The buried red braid is part of the book’s imagistic pendulum, the swing of grief’s range from rage to disbelief to hope and back. Techniques of repetition convey the brutality of this unreal ordinariness. But there are things only the poem can say of the world that is poetry.

Echoing across time and space, one thinks of Czesław Miłosz’s “A Song on the End of the World,” a poem written in the war-torn Warsaw of 1944, as the viciousness of humanity disfigured the planet. “There will be no other end of the world,” Miłosz tells us in a closing repetition. “There will be no other end of the world,” he insists; this time, this moment, this witness, is all we are given. The poet must write it. Eyes ablaze, Farris stands inside these poems, leaning her weight against the point where death and life meet, where life and death stand so close that the page would catch fire if they spoke an additional word. The poet picks up her pen. The forest may burn, but the poem will remember every minute.

Alina Stefanescu serves as poetry editor for several journals, reviewer and critic for others, and co-director of PEN America’s Birmingham chapter.

Alina Stefanescu serves as poetry editor for several journals, reviewer and critic for others, and co-director of PEN America’s Birmingham chapter.