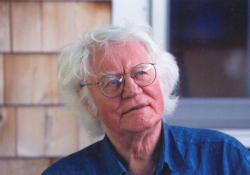

The Short-Story Physicist: A Tribute to Ignacio Padilla

Translator’s note: Mexican writer Ignacio Padilla (1968–2016) was killed in a car accident on August 20 while traveling through the Mexican state of Querétaro. He was forty-seven. The author of twenty-nine books and recipient of numerous literary prizes, Padilla was a founding member, along with Jorge Volpi, Eloy Urroz, Pedro Ángel Palou, and Ricardo Chávez, of the “Crack Movement,”1 which sought to break from the Boom, whose themes and motifs, the young writers believed, had grown stale and irrelevant to a changing Latin America.

*

To many of us Ignacio Padilla was “Nacho,” the traditional hypocoristic for Ignacio, an affectionate nickname used not only by his family and closest friends but also by his students, admirers, colleagues, and readers. Nacho Padillo was well liked: we felt close to him. His work—despite being erudite, cerebral, even strange—was deeply admired: readers who otherwise would have rejected more obliging texts written by other authors surrendered happily to those written by Nacho, where they found, without fail, the best in each of them.

This was no small achievement: writers like Nacho will always be rare, unusual in the world of writers, even more so in the Mexico of recent years. Perhaps because of the influence of the violence that surrounds us, it has become “normal” in Mexico for certain colleagues to be—or appear to be—conceited or aggressive, to display these same qualities in their public life and even attract admirers because of them. Their insults have become an escape valve for other people’s frustrations, illusions of power for those who feel helpless. Nacho, on the other hand, did not project arrogance or anger but rather intelligence, humor, and empathy. He was a great conversationalist who knew how to laugh at everything and disarm solemn people with such grace that even they ended up laughing. During his long career as a university professor, he was generous with his students, captivating them with long digressions on his favorite topics whenever one made its way onto a syllabus. He invented playful nicknames, the first of which was his own, dubbing himself the “físico cuéntico,”2 a reminder that, although he had written novels, essays, and theater and had earned prizes in each category, in Mexico and abroad, he was first and foremost a writer of cuentos, or short stories: a practitioner of that ancient and sometimes misunderstood genre.

Padilla’s interest in the author of the Quixote, in his brilliant century and in the vigor of his language, was present in all his work.

Needless to say he was a great, great writer. His passions could be found even in those texts where they were least visible: he remained faithful to those peculiar forms that he gave to his stories, to the monster as figure and symbol, to the subtle, unbowed imagination—in fact, many of his stories are the product of a fantastical imagination, although he managed to escape being read as an inhabitant of the ghetto known as “genre fiction,” where so many careers go to die—and especially to the Spanish language. He received his doctorate in Salamanca, Spain, with a dissertation on Cervantes, but his interest in the author of the Quixote, in his brilliant century and in the vigor of his language, was present in all his work. At the time of his death, he was a member of the Mexican Academy of the Spanish Language; his induction address, “In Praise of Impurity,” was a splendid essay in defense of the subversive nature of Cervantes’s work: a call to open up thought and perception of the world beyond the limits imposed by authorities (or by tyrants).

Part of his work is translated into various languages; in English, for example, there is his novel Shadow Without a Name (Amphytrion), a Borgesian thriller set during the First World War, and his short-story collection, Antipodes (Las antípodas y el siglo). Yet to be translated, however, is his adventure novel, La Gruta del Toscano (The Tuscan cave); the short-story collections El androide y las quimeras (The android and the chimeras) and Las fauces del abismo (The jaws of the abyss); or the essays, El legado de los monstruos (The legacy of monsters) and Cervantes y compañía (Cervantes and company). In these works, I believe, is encoded the journey of a reader who walks out of a library and encounters the world, with all its horror and beauty, but who never loses faith in language as a possibility of knowledge, of orientation in chaos.

Padilla’s works encode the journey of a reader who walks out of a library and encounters the world, with all its horror and beauty, but who never loses faith in language as a possibility of knowledge, of orientation in chaos.

Lastly, Nacho did not just project cordiality: he was, in fact, a great guy, generous and congenial, even to those of us who saw him infrequently and passed through his life only briefly. He was a longtime friend to many colleagues, especially with his counterparts in the so-called Crack Movement, those novelists who dared to launch a literary manifesto at the end of the twentieth century and thereafter were forever present in the country’s collective imagination. My contact with him was more recent, as professors at the same university, where we were brought together by presentations, readings, prologues, anthologies . . . so his death in a car accident last Saturday, August 20, was not only a hard blow, because it was horrendous, sudden, and profoundly unjust; it also wounded me, like it did so many others, because the man behind the books has disappeared.

Now we’re left with those texts: traces of his thought, still able to offer us the provisional truths that Nacho discovered and was able to express during the course of his life. But we are going to miss him a great deal.

Mexico City, August 25, 2016

Translation from the Spanish

By George Henson

Footnotes:

[1] When asked about the origin of the movement’s name, Palou said, “While boom meant explosion, crack represented to us the sound of fissure, of rupture.”

[2] Padilla’s wordplay is as brilliant as it is impossible to translate. Borrowing from the Spanish adjective cuántico or “quantum,” Padilla coins the adjective cuéntico from the Spanish cuento or “short story.” Hence, rather than a “quantum physicist,” Padilla sees himself as a “short-story physicist.”