Koko and Raden

If only people loved one another and learned to save money, if only the children at the orphanage could get foster parents, if only the sun shone brighter . . . All these are wishes of little Miss Koko with the gnawed fingers—biting her fingernails isn’t enough, so she actually chews her fingers. Just as she doesn’t stop at her nails, neither is she ashamed of her emotions toward dogs. Koko reached the peak of her activism when she found a hip replacement for a cocker spaniel. The donor dog had a heart defect; Raden heard for the first time that a dog could have a heart defect. Raden is an IT specialist. He has a slightly larger head and a slightly smaller ego, and everything about him is slightly different. Koko smiles and serves him scrambled eggs.

This is slightly oversalted, Raden says, and Koko posts that as her status, slightly oversalted, hmm . . . Every one of her 4,300 friends knows Koko is a master of turning eggs, mushrooms, and mortadella into a good debate—how is it possible that Raden not appreciate her efforts in the kitchen; on the other hand, Raden just burped (that was the elderberry syrup in mineral water) and threw himself onto the couch from where he can watch Koko clearing away the table. The chandelier started to shake again. Again, Raden tweeted. Everyone is already used to it; only their tomcat Fritz is still afraid and has gone gray with fear. Raden types on the screen using just his thumb, replying to name-calling and rude comments—the greatest compliment to a cook is when you tell her frankly how the food is. The chandelier has come to rest now. Fritz scratches at the door and tries to call Koko, who has stuck her head into the dishwasher.

What does Koko think about cremation? Koko is for. Raden is against because he likes worms, or is that just a pose? You never know with people like him.

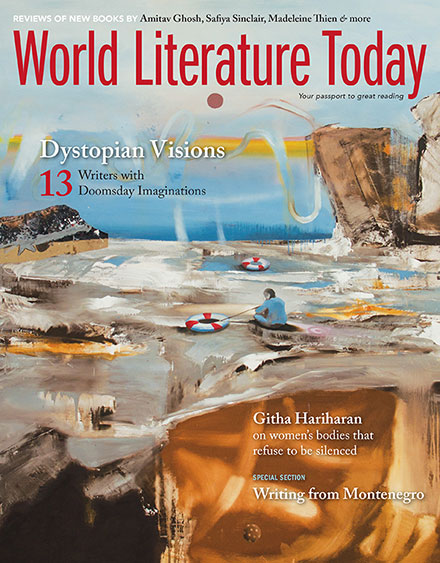

What does Koko think about cremation? Koko is for. Raden is against because he likes worms, or is that just a pose? You never know with people like him. Raden therefore has a mass of followers. He’s the god of the good tweet and his voice is heard throughout the Internet. Why is it important how long someone’s penis is, Raden asks himself. The anxiety that seizes a man dissatisfied with his body is terrible. Raden grew up in the small town of Cetinje, formerly the capital of the illustrious kingdom of Montenegro. Its houses are like boats launched by the sweet stench of history into the sleepy streets with their tired lindens. Or without the tired lindens, so as to fit in the 140-character space together with the English translation. Raden tweets bilingually. He writes poetry—he always has in secret—and now he can go on with it, except that no one recognizes its poetic worth. Everyone sees it as a joke. He got what he wasn’t looking for, but at least that’s something, so he keeps on with his verses and his audience retweets them, convinced that Raden is just messing around for fun.

Koko was born in 1973 in Vienna. All her life, she’s always said she was born in Vienna and licked her lips. She’s never uttered the name of that city without running the tip of her tongue over her upper lip. She moistens it, then her tongue returns to her mouth and captures people’s attention. Koko often has colds and Raden makes ginger cookies for her. Fritz the cat loves them. None of this is out of the ordinary, and all of it has been posted on the Web already, Koko thinks, looks at Raden, and notices that he isn’t exactly attractive. She isn’t satisfied with his appearance. Still, the pandemonium with the earthquake and the scandal of the government parroting that everything will be all right is more than Koko can stand. Raden was the only person who accepted and fully understood her idea. The puppies can wait, he said. That slightly hurt her feelings. Raden was able to offend slightly. But however much she looks down on people, Koko knows that human lives are worth more than dogs’. Koko is social-media manager at Telekom, and who else would think up a Twitter-based warning system if not her? Cut the crap. If you didn’t like dinner, fuck you. She added a smiley. Then she wrote: Three on the Richter scale, guys! Better take a plumb-line with you to bed. Another smiley. Or plum brandy, Raden added. Koko faved that, which means exactly what a normally intelligent person thinks of—there was no frantic sex, dripping wax on Raden, bondage, and beating in aromatic almond and lavender oil. None of that.

The day an earthquake hits Cetinje, as the saying goes, all cities will feel it. And did it hit! Raden went to the window and saw the sun. And the sun revealed the full scale of the cataclysm—roofs aglow, firebirds pining cozily in the rotten spectacle of fall’s first conquest. He tweeted. This is hell. Houses smoked, while children and their parents cried out for help. There wasn’t a single intact building to be seen. A large crane had fallen onto the playground of a kindergarten, where yellow-helmeted journalists were now flocking. Worms are perhaps not so pleasant after all, Raden thought. It had all just been his posturing. A column of ambulances was stranded in the Crmnica range, where the road had been cut in several places. The city administration retweeted each of Raden’s warnings, but also his poetry. No one found it funny this time. Raden opened up completely, and one portal followed the flow of his thoughts live. Koko came back from the field exhausted and breathless; she didn’t use the elevator out of fear. The danger passed. It never strikes in the same place twice. Koko would be awarded a medal because the children were saved thanks to her warning, but she wouldn’t have children of her own. She just had Fritz. And Raden, who had to make up his mind. He said he needed time to think. Koko took a dish to the trembling cat.

They flew the coop when things were hardest, but Koko was born in Vienna and had no problems with her conscience. She’d done as much as she could by saving the lives of the children.

Raden agreed that they try it in Vienna. He hadn’t planned for them to marry there. As they were taking off, he looked through the window and saw the airport tower like a wire crucifix with a red beacon on top. They flew the coop when things were hardest, but Koko was born in Vienna and had no problems with her conscience. She’d done as much as she could by saving the lives of the children. Now she was a hero and would only speak to journalists online. Koko hoped the quake might improve things; she wanted it to be a good sign. She still had a little faith that her body and Raden’s testes—oh damn it, balls—could get it together to create something. She didn’t sleep in the same room as the computer. That was no small sacrifice. But she had a digest of the tweets via her phone, and she threw all other sources of radiation out of the bedroom. Fritz stayed behind to cope as best he could out in front of their block. Everyone loves Fritz, a cute cat with a little bell around his neck. And they know Koko from television, where she told everyone: “It was Fritz who felt the quake before it hit. And I admit that I tweeted the now famous words on my own initiative, before confirmation came from Emergency Services.”

Raden didn’t like Vienna. He sat around with some Russians, drank beer at a small bar out on the sidewalk, and followed an austere shadow that he felt showed every single minute. Two beers were enough to make him drunk, and by that time the shadow had swallowed the table. A large leaden door brooded like a bunker on the other side of the street. He watched the prostitutes going in; it was the rear entrance of the Babylon, a public house of special significance in the city. Everyone had heard of the Babylon, and the ladies were excellent and refined. Koko and Raden sometimes sat together with the Russians and watched the prostitutes arriving for work. Amiable and cheerful they were, the kind of women he would like to have by his side, and the way they greeted the porter, a gentleman with a shiny forehead—all this was pleasant for Raden, but also for Koko. Everything was better than thinking of the country in ruins they would have to return to.

The year passed, and Koko and Raden have a child they named Kolin. A very large-headed boy. It had made sense that they kept at it. Now it’s a hot summer, and no one mentions the earthquake. Koko went back to her old job, she’s a fat pig and knows it herself, but now she at least has Kolin. Raden began his own business after telling his boss to fuck off. He started with rags. He really is particular. I mean, who else would come up with the idea of selling cloths for cleaning computers? Chinese junk, Raden managed to find a microfiber that you can draw on, and when you run your finger over the fabric it leaves a trail like in sand. Not just textiles but also small furniture, fancy goods, and everything the average consumer desires. Raden has become a businessman. How is that possible, Koko asks herself. But she doesn’t care about anything anymore. She’s made a glasswork window of a dog sitting and watching a cat, which is sitting and watching a rabbit, which is sitting . . . etc.—ten rows of little animals, all in primary colors—and when the sun rises Fritz goes mad from the light that floods over his naked owner. Koko likes to breast-feed naked. Raden looks at her like she’s a foreign object. The fire in him has already gone out. But they have a child, you have to admit. “At least she’s not a bleeding-heart pet rescuer anymore,” the neighbors say.

I’m one of the neighbors who hears their altercations, and I’ve called the police countless times as well as the Child Welfare Department. You can contact them over the Internet nowadays. Take Kolin from them, I wrote. I knew the child was up shit creek with parents like that—colorless, heartless people, fucked-up activists. I asked myself if Koko and Raden were biodegradable or if their souls would burn up and glow on Judgment Day like the sun above the ruined city.

Translation from the Montenegrin

By Will Firth