“Art Should Make You Uncomfortable:” A Conversation with Vu Tran

Author of the noir novel Dragonfish, Vu Tran teaches English and fiction at the University of Chicago. Also a contributor to the collection of essays The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives, Tran left Vietnam at age four and grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from the University of Tulsa then obtaining an MFA from the University of Iowa and a PhD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. While visiting Oklahoma City to speak to students in Oklahoma City University’s Red Earth MFA program, he sat down with WLT’s managing and culture editor to discuss the best teacher he ever had (spoiler alert: she was tough), his work, the role of language in dehumanizing others, and why art should make you uncomfortable.

Michelle Johnson: In the acknowledgments following your first novel, Dragonfish, you individually thank several teachers, beginning with your twelfth-grade English teacher, Pat Sherbert, who taught you “how to value literature.” That’s really important. How did she do that?

Vu Tran: Well, she was the most important teacher I think I’ve ever had—definitely the most important one through high school. I’d always loved books, but she taught me that books aren’t just about entertainment. They can be read in many different ways, according to when, where, and why you’re reading them, and they teach you a seriousness of mind that can be applied to every aspect of your life: your job, your relationships, your approach to the world. She taught me that art isn’t just about beautiful things but about ugly, uncomfortable things, and that these things often get closer to the truth. Art is a mode of living, not just something you engage with now and then for aesthetic edification. She taught me all these things, and she was a very tough teacher.

Johnson: It seems like when people look back and name their most important teachers, they’re usually tough teachers.

Tran: Yeah. And now I’m a tough teacher as well. But it’s not about being tough for the mere sake of it. It’s about being honest with your students so that they can then be honest to themselves, because without that level of truth and commitment, you can’t get better, no matter what you do. But yes, she was my first truly tough teacher. I learned so much from her.

Johnson: Had you already started thinking about being a writer before then?

Tran: Oh yeah. I knew I wanted to be a writer in the first grade. Mrs. Sherbert didn’t distract me from that, but she kind of put me on the path to being a scholar. In college, that was my plan, to be a professor of English and then write creatively on the side. When I went off for my MFA, I discarded those plans. My intention then was to be a writer and nothing else. But of course, it’s hard to be a professional writer these days without also being a teacher, so I ended up a professor after all, but I quite like being a teacher, so that worked out for the best.

I think finding your voice is basically the process of learning the craft and gradually revealing who you are to yourself. Learning to write a good sentence allows you to be more honest and more truthful in your work, and that’s when your “voice” emerges.

Johnson: Reading about you as a teacher online, my impression is that as a teacher, you emphasize helping students find their voices. Voice is something that is very mysterious to people sometimes. Who helped you find your voice, and how do you help people find their voices?

Tran: I think people sometimes mistake voice for some kind of original style, this precious, authentic thing inside you that you have to excavate somehow, and I’m not sure that that’s it, at least not entirely. I think finding your voice is basically the process of learning the craft and gradually revealing who you are to yourself. Learning to write a good sentence allows you to be more honest and more truthful in your work, and that’s when your “voice” emerges. It then becomes a matter of constantly asking yourself, “Do I really believe this?” It’s weird how we fail to do that. It wasn’t until my late twenties that I would write a sentence and then stop and ask myself, “Actually, do I really truly believe this?” It’s amazing how often the answer is no, which is when you go back and rethink the thought and rewrite the sentence until you get something that is truly true, that is actually you. Most of what we write at first is a mere regurgitation of other people’s ideas of truth. Finding your voice, then, is the process of finding your own truth: your vision of the world that is specific to you. Style is part of it. Tone is part of it. And good sentences are a big part of it. But the “voice” itself can only come out of you being brutally honest with yourself.

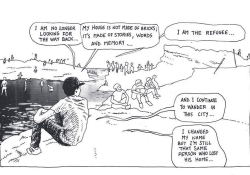

Johnson: You’re a contributor to a new collection of essays, The Displaced, just published in April. In his introduction to this collection, Viet Thanh Nguyen talks about the difference between calling himself an immigrant and a refugee. He says that an immigrant is “less controversial, less demanding, and less threatening than a refugee.” But sometimes we see people using ominous words like “flood” and “invasion” in reference to immigrants. In your essay, “A Refugee Again,” you talk about thinking of being a refugee as a past state, later becoming an immigrant. How do you view these terms and the uses of these terms now?

Tran: It’s something I didn’t think a lot about until the last five years, really. Viet Nguyen in many ways helped me think about it. That essay came out of me wondering: Do I still call myself a “refugee”? Wasn’t being a refugee a temporary thing? Once you’ve found refuge, are you still a refugee? Aren’t I an “immigrant” now? I wanted to explore these questions and what it means to call myself a refugee and how being one has affected my upbringing and my adulthood here in the States. And I realized it affected me more than I thought.

For example, coming out of that experience themselves, my parents raised me very protectively—too protectively. When you grow up in that bubble of safety, you’re ignorant to a lot of things. You’re ignorant, ironically, to your own refugee status. My parents—ironically—also raised me to be strong and proud and self-reliant, which is great, but that made me resist the notion of myself as a refugee. The word tends to suggest vulnerability: someone in need, someone who needs to be saved. I think it’s more beneficial to think of a refugee as someone defined not by their need but by their desire. The desire to protect themselves and those they love. The desire for a better life, a new life. A life open to possibilities. The reality, however, is that most people think of refugees in terms of their need and their victimhood—as someone holding up their hand and pleading with someone else to pull them up. That’s definitely part of the experience. It’s what I went through for sure. But that’s not the only or even biggest part of it.

I think it’s more beneficial to think of a refugee as someone defined not by their need but by their desire. The desire to protect themselves and those they love.

Johnson: The terms that we use are so important.

Tran: It’s important because language so affects how we think of a vast population of peoples. Just think of the label “illegal alien” and how the negativity of those terms has affected how we approach immigration in our country. Words like this end up overwhelming the identity of a people, and it also helps to dehumanize them. When you dehumanize people, it makes it much easier to not help them, to be indifferent to them, which is actually worse. So yes, the terms are crucial.

Johnson: In her essay for the collection, Meron Hadero writes about her earliest memories: “My remembered life began in that time of becoming and being a refugee.” She reached Germany from Ethiopia at two and left there for several months after her third birthday. As someone who left Vietnam at age four, do your earliest memories similarly bridge this time of leaving and arriving?

Tran: Not exactly. My first extended memory is actually of my very first morning in America. I had only met my father for the first time the night before. He had fled Vietnam before I was born. So this strange man takes me to the kitchen and makes me a bologna sandwich. He toasts the bread and microwaves the bologna. He gives me sweet-and-sour Ruffles potato chips and 7 Up. All these things were entirely new to me, and to this day I still love them all. And after breakfast, I remember going into my bedroom and riding around on this plastic duck that he had bought for me and my sister. That whole morning is a complete memory in my head. All my memories before that day are just vague fragments and images, even of those days on the boat escaping Vietnam and my time in the refugee camp, which all occurred only months before I got here. I find it so odd, you know, that my memories truly started on my first day in America. But maybe it makes complete sense that my mind would memorialize a day that must have been overwhelmingly new and strange and comforting to me.

Johnson: I’m reading Viet’s introduction to The Displaced, reading about his family’s experience as refugees living in San Jose in the 1970s and what they endured, and I’m thinking that every generation of US citizens inflicts some of the same abuses on refugees. It’s history repeating and repeating and repeating. How do we break this cycle?

Tran: I don’t know.

Johnson: That’s a big question.

Tran: We break the cycle with leadership? Not having bad leadership.

Johnson: Good leadership.

Tran: Because leadership ends up controlling things like the language we use to label people and to describe their experience. When you hear your leaders define immigrants and refugees in a certain way, and you get legislation that does that too, the culture will follow suit. I’ll put it this way, and this is just my personal philosophy—but if you approach anything with fear, that approach will be problematic. Especially when you’re dealing with other human beings. I really think that should be our number-one goal when it comes to addressing the issue of immigration: to not approach it with fear. That can be incredibly difficult, of course, especially in times of war and national tragedy. Certainly, it was tough after 9/11 not to be afraid of so many different things.

So yes, certain circumstances make it hard to keep fear out of the equation, and we should always try our best to protect ourselves and those we love. But we must also be mindful of how corrosive fear can be to the soul of anyone, let alone a people and a nation. I can’t think of much good that comes out of it. Fear degrades our relationship with everything in life: our friends and family, our romantic partners, our profession, our art.

Johnson: Aleksandar Hemon writes about literature providing “individual narrative enfranchisement”—a way to combat the “dehumanization and deindividualization” that enables bigotry. But in his introduction, Viet Thanh Nguyen cautions that “literature does not change the world until people get out of their chairs, go out in the world, and do something to transform the conditions of which the literature speaks”—the action following the change of heart and mind. How do you view the role of literature in effecting change?

Tran: That’s a really complicated question. I feel like literature does do what Aleksandar is saying: it teaches us empathy, which is not merely sympathy. Literature teaches us how to imagine ourselves in other people’s shoes whether they’re good people or bad people or something in between, and we’re all usually something in between, right? On top of that, Viet is adding a call to action. You can’t just passively engage with the world around you as you might with literature. You have to take action.

Personally, I’m very politically conscious and engaged, but I’m not an activist like Viet is. I’m simply not built that way. I have too many doubts and uncertainties about everything. But I do believe deeply in the critical role that art and literature plays in any society. The thing is, our society is constantly trying to convince us that everything is okay. I’m not necessarily anticapitalist, but capitalism is set up to tell us that. Eat this bag of Doritos, drink this can of Coke, buy this or that, and you’ll be okay in the morning. I love pop culture, but a lot of pop culture is designed primarily to entertain us, and it’s hard to entertain people when they’re not feeling okay. Our education system gives us a similar message: learn these things, get yourself a good job, make good money, and you’ll be fine. All these institutions are set up to maintain the status quo, because the status quo makes people feel safe and stable enough to buy into the things those institutions are selling.

Art, on the other hand, is set up to tell you that things are not okay, that the world is unstable and problematic. Art is hard to define, of course, and it arguably sells people on a kind of status quo as well; but the kind of art I’m referring to makes us uncomfortable and forces us to see the world in a new light. That’s not always easy to engage with. But seeing the world in a new light allows you to see all the possibilities that the world offers, and I find that a very inspiring thing.

Johnson: And perhaps change the way you think about something, ultimately.

Tran: Absolutely. People are afraid of change. Religion is another one of those institutions, and it’s set up to convince people that everything should stay the same, that change is the enemy of virtue and devoutness. Art, however, thrives on change. Science does as well. Change enables us to see things in ways we’d never seen them before, and that’s so generative and open and wonderful to me. When everything is full of possibility, that’s my personal definition of happiness.

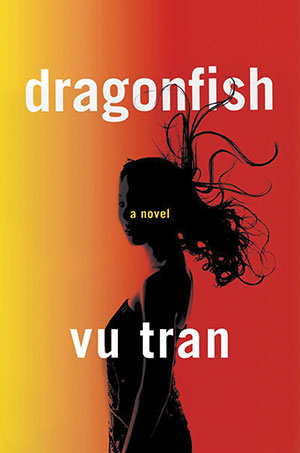

Johnson: Let’s talk about Dragonfish, your novel. Writing about Dragonfish for the Chicago Tribune, Lloyd Sachs called the book “transfixing” and said that, “like such writers as Caryl Phillips, Dinaw Mengestu, and Edwidge Danticat,” you are “devoted to capturing the immigrant experience and widening everyone’s understanding of its particular as well as universal truths.” In addition to writing a literary thriller, were you intending to widen your readers’ understanding?

Johnson: Let’s talk about Dragonfish, your novel. Writing about Dragonfish for the Chicago Tribune, Lloyd Sachs called the book “transfixing” and said that, “like such writers as Caryl Phillips, Dinaw Mengestu, and Edwidge Danticat,” you are “devoted to capturing the immigrant experience and widening everyone’s understanding of its particular as well as universal truths.” In addition to writing a literary thriller, were you intending to widen your readers’ understanding?

Tran: Yes, but I don’t put it that way because I don’t approach writing as trying to educate the reader. For me, writing is very personal and self-centered. My ideal reader is myself, and I wanted to write a book that I would find thrilling and mysterious and even sexy. Which was why I was working in the noir genre. But I also thought the genre offered me a rich space to work out things that I’d always been curious about. I’ve always been curious about motherhood and my mother’s experience fleeing Vietnam with me and my sister. I’ve always been curious about white Americans who are drawn to Vietnamese people or the world of other immigrants. I’ve always been curious about outsidership, that feeling of alienation and estrangement from others. I felt like writing a crime novel, a noir novel—where everything is in the shadows and therefore always incomplete and ambiguous—would be a great framework for me to explore these things that have always been a wonderfully intriguing mystery to me.

Johnson: Is the novel you’re working on now going to be a thriller or something else?

Tran: All I can say right now is that it’ll be something of a gothic novel. Crime fiction comes out of the gothic tradition, and I think Dragonfish is gothic in many ways. With this book, though, I want to work more specifically in the tradition of novels like Rebecca or The Magus. I like working within genres. The framework really helps me write. It gives me structure and guidance.

Johnson: Beyond writing and literature, what are your current obsessions? What distracts you and keeps you from writing your next books?

Tran: TV is a big distraction. There’s just so much great TV out there.

Johnson: I agree. What are your favorites?

Tran: I love all the usual suspects. Breaking Bad is a big one for me. I also loved The Sopranos, Mad Men, Game of Thrones. I think the best show I’ve seen since Breaking Bad is probably The Terror, which just came out on AMC this past year. It’s an incredibly weird and gorgeous and brutal show about the various ways that we confront and combat fear, the biggest fears being death and the unknown. I can’t say enough about it. It’s magnificently acted, directed, and written, and I learned a great deal from it as a writer, beyond just being very inspired by it. I get distracted from writing because of my TV watching, but I’ve also learned so much from it. I think anytime I engage with other kinds of art I’m learning a lot, whether I know it or not.

Johnson: You live in Chicago. Where do you go for inspiration?

Tran: I don’t go anywhere for inspiration. When I go looking for it, I rarely find it. The best thing you can do, I think, is to live your life and simply open yourself up to things. If you’re open, the most unexpected things will end up inspiring you. I’ve been inspired by everything from a trip to the museum to a trip to the grocery story. That said, nothing gets me going like a good book or a good movie or good music.

Johnson: What are you listening to right now?

Tran: My favorite band is probably Beach House. They’re actually quite gothic in their sound.

Johnson: It’s a good soundtrack for you while you’re writing a gothic novel.

Tran: Absolutely. But they’ve been that way for me for a good eight years. I don’t like having favorites of anything, but I can easily say they’re my favorite contemporary band.

July 2018