“The Ephemeral Condition of Concrete Things”: A Conversation with Sergio Chejfec

Sergio Chejfec is an Argentine writer based in New York City. Born in Buenos Aires, from 1990 to 2005 he lived in Caracas, Venezuela, where he was editor of the journal Nueva Sociedad. He is the author of eighteen books of fiction and nonfiction, a number of which have been translated into French, English, German, Hebrew, Portuguese, and Turkish. A recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, he currently teaches workshops and advises students in the graduate creative writing program in Spanish at New York University.

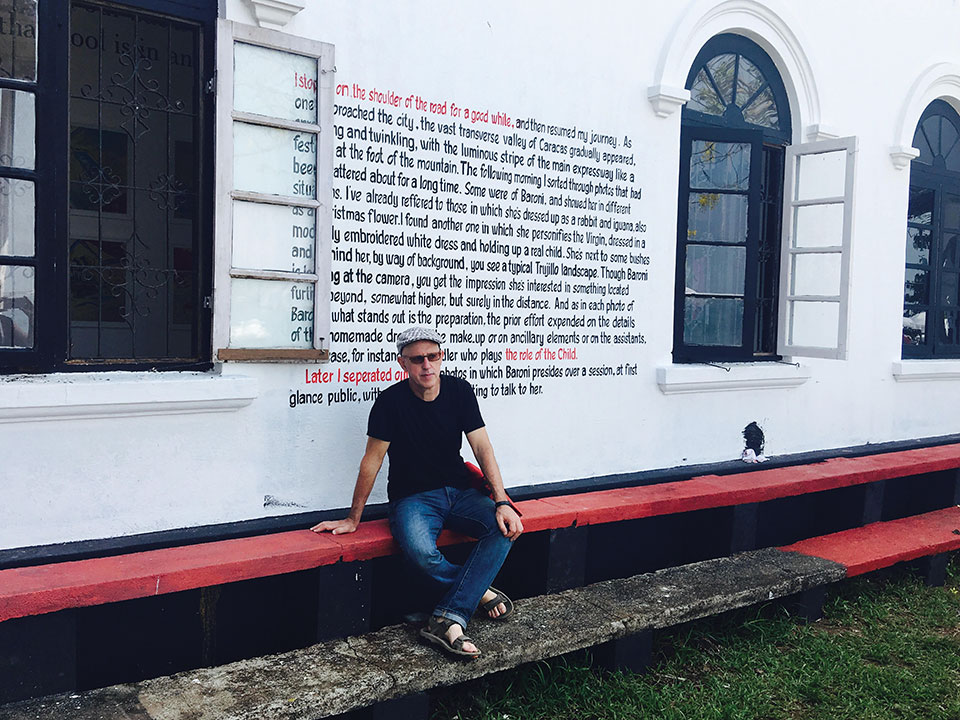

Graziano Krätli: Your latest book, Baroni: A Journey, translated by Margaret Carson, has an interesting prepublication history. It made its first public appearance, not as a bound volume, but in the form of an art installation at the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, where portions of it were pasted on the walls of Kochi, in the southern Indian state of Kerala, in no less than ninety different locations. As a matter of fact, Dissemination of a Novel is the work of a visual artist who is also the author of the book depicted, while the book itself is about a real artist, Rafaela Baroni, who is no stranger to dualistic implications. Can you talk about your experience at—and of—the biennale? How did you happen to participate as an artist (rather than, say, a creative writer or a critic)? And how, where, and when did the idea of this particular installation originate?

Sergio Chejfec: One of the things that excited me most about the biennale was its particular location, in a corner of the map of India. The opportunity to participate in an event that was taking place off the beaten path struck me as very appealing. The organizers of the 2016 edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (December 2016 through March 2017) invited several writers, with the idea of stimulating cross-pollinations between literary order and art installation. The main venue [Aspinwall House] is an immense building facing the sea, an old colonial structure where goods were stored and administrative offices located. Inside are open spaces, large buildings of different types and belonging to different periods, etc. Everything was a bit old and sturdy at the same time.

What I found most appealing in the possibility of writing the novel on the city walls was precisely the form of “deviant dissemination” of which the text would be the protagonist. Literature is disseminated in the form of a book (even if it is digital), that is, a unitary sequence of words or phrases. In the streets of Kochi there would be an “aliterary” dissemination, since nonconsecutive fragments of the novel would be written on different walls. There would be a physical dissemination, the undoing of a unity already irrecoverable in that support (the walls), and also a material dissemination, given the accelerated deterioration of façades and walls in a warm coastal city. In other words, the novel would turn into a ruin, and in the short term it would become illegible even for those willing to pay a visit to each written wall.

I liked to think of a silent text, without marks of origin, even though blocks of text belonged to the same novel. It was an ephemeral possibility of betting on material anonymity. And it was also the opportunity to adhere to the ephemeral condition of concrete things, something that for literature is unthinkable due to its imaginary condition.

I liked to think of a silent text, without marks of origin, even though blocks of text belonged to the same novel. It was an ephemeral possibility of betting on material anonymity.

Krätli: What I find particularly interesting, in Dissemination of a Novel, is the way it hints at the multiple manifestations of what we call “a book,” a word that may refer to the intellectual and creative content of a literary work, its physical (or digital) container, or the contexts of its material production, circulation, preservation, and consumption. (It would be interesting to know Rafaela Baroni’s thoughts about the installation, if she were aware of it, but we’ll leave that for another interview . . .)

By the time of Baroni’s participation at the biennale, plans for a more traditional form of dissemination were already under way. Could you tell me how this, your fourth book to be translated into English, came to be published by a small, independent press based in Mumbai?

Was the book publication an outcome of your participation at the biennale, or the other way around? And what was your experience of working with Almost Island?

Chejfec: The Almost Island initiative is particularly dynamic, showing an organic curiosity for literature that, moving from the periphery, is not seen as peripheral; proof of this ongoing interest is the online journal with the same name. Its founder and publisher, the poet and writer Sharmistha Mohanty, was among the participants of the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Somehow, she was the link between the biennale and my participation. At that point, Almost Island’s publication of Baroni had already been decided. So, my dissemination of the novel on the walls of the town was my last opportunity before the text took the shape of a book.

As for the publication itself, I suppose that this is due to the intellectual curiosity and hospitality of Almost Island. There is an implicit affinity between a novel that takes place in Venezuela, is written in Castilian, by an Argentinian living in New York, and is published in India. Or, to be more specific: Caracas (where I lived at the time), New York (where I wrote the novel), Buenos Aires (my hometown), and Mumbai (where Almost Island is based). This affinity speaks of a reality that is diffuse yet visible: what, in geopolitics, is called South–South cooperation. It is a very deliberate approach for Almost Island, which tries to articulate its presence from canons that are not so implicit.

Of course, the biennale saw the participation of dozens of visual artists and five or six writers. I found it difficult to accept the fact that my project was not linked to writing, perhaps because it was the first time.

Krätli: Prior to Baroni, three other books of yours were translated into English and published by Open Letter, the University of Rochester’s literary translation press: My Two Worlds (2011), The Planets (2012), and The Dark (2013). What led you to this particular publisher, or what led them to you?

Chejfec: Chad Post, Open Letter’s publisher, is a reader of insatiable curiosity and a wonderful promoter of literature. One time he read in a Spanish blog that Enrique Vila-Matas recommended one of my books, Mis dos mundos (My Two Worlds), and mentioned the comment in the Open Letter blog, Three Percent. At the same time, Margaret Carson was about to publish an excerpt of this same novel in BOMB magazine. When she read Chad’s entry, she contacted him to propose a translation of the entire book. So in this case, too, things happened as a result of external and casual circumstances. And in 2019, they are planning to bring out The Incomplete Ones, Heather Cleary’s translation of Los incompletos (2004). Moreover, I feel very comfortable with Open Letter, with which I have an affinity in the fact of observing literature in an open manner, without hierarchies of any kind. I like the fact that Open Letter operates as if it were a project of literary utopia. One could argue that, as a publisher dedicated exclusively to translations, everything that is not written in the United States passes through there—and that in this way the press represents an attempt to modify that landscape through negative operations.

Krätli: Between 1992 and 2012, most of your fiction books were published by Alfaguara, the house founded by the Spanish writer Camilo José Cela. In 2013 Alfaguara became part of the newly formed multinational group Penguin Random House and is now one of its “nearly 250 editorially and creatively independent publishing imprints” (to quote from the group’s website) under the new name Megustaleer. Since then, you’ve published mostly with independent presses such as Bajo la Luna, Entropía (both based in Buenos Aires), and Jekyll & Jill (based in Zaragoza, Spain). The latter has been called “a factory of small bibliographic fetishes that has conquered the most demanding readers” (una fábrica de pequeños fetiches bibliográficos que ha conquistado a los lectores más exigentes), a definition I find troublesome as it seems to underwrite, or at least to take for granted, the fetishization of literary fiction as a natural consequence of media comglomeration as exemplified by the Alfaguara story. What is your experience, and what are your thoughts, in this respect?

Chejfec: The 1990s saw a significant expansion of the Spanish publishing industry, with a few large firms turning into media corporations with major offices in all the Spanish-speaking countries. This expansion affected the educational market as well. Simultaneously, the same Spanish publishers began to consolidate and sometimes ended up as subsidiaries of global publishing corporations. I think that in Latin America the effort was aimed at occupying reading markets to optimize large catalogs. For local authors, this involved the implicit promise that their books would circulate in other hispanophone countries, since the same large publishing house was based in each one of them. This didn’t always happen. Then, as a result of technological innovations in book production, a number of small publishing houses started to operate in many countries with a concern for book proposals that were more alternative or less market-oriented. In my case, despite publishing with a large house like Alfaguara, I was never a commercial author. At a certain point I felt that the presence of my books in their catalog was a matter of routine. And because of the distribution policies of large publishers, my books did not reach the kind of outlets (independent bookstores) where they might have a better reception. That’s why I started publishing with Entropía in Argentina and with other small publishers in Chile or Peru. In Spain, I have published with Candaya (Barcelona) and, as you mentioned, with Jekyll & Jill (Zaragoza).

Krätli: Teaching is another form of dissemination, involving knowledge and skills, a particular weltanschauung, conveyed in a different way from that of a published text. For a number of years you have been teaching creative-writing workshops and advising students in fiction and nonfiction writing. What has been your experience, and what impact has it had on your own writing (if any)? I am interested in what you’ve learned more than in what you’ve been teaching, of course.

Chejfec: I am not quite sure because since I started teaching, my writing has turned progressively to a form a little more distanced and, let’s say, thinking than before. And yet it was already distanced from the beginning. It is as if the oppportunity of being in contact with young writers has made me feel my own literature as a more private discourse. Teaching is not for me to transmit a specific knowledge related to techniques or procedures; I don’t know very well what it is. If I had to define it, I would say that somehow it is to expose a sensitivity. This ongoing conversation with young authors is extremely dynamic and, if you can say so, intellectually stimulating.

Teaching is not for me to transmit a specific knowledge related to techniques or procedures; I don’t know very well what it is. If I had to define it, I would say that somehow it is to expose a sensitivity.

Krätli: To end at the beginning. What I find particularly interesting and visually intriguing in Dissemination of a Novel on the walls of Kochi is the medium employed to accomplish this particular installation. The text was manually composed on a white coat of paint, ruled and rubricated to look like a manuscript leaf. In fact, the result may be called a “mural manuscript,” or a manuscripted mural (with a nod to Kerala’s own tradition of mural painting). You have written more—and, in my opinion, more interestingly—than any other contemporary writer about the technology and practice of writing, as in Últimas noticias de la escritura (2015), a book I hope will be translated soon, in English as well as other languages. What makes your writing on this subject particularly original and fascinating, in my opinion, is the creative and speculative ease with which you explore different technologies of writing, rightly ignoring the traditional yet largely artificial divide between manual and mechanical practices (since hands are used for both handwriting and computer-writing), to concentrate instead on their potential for interaction and cross-fertilization. In this perspective, your installation at the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale adds a new dimension to a topic you have been exploring in print. Would you please elaborate on your interest for writing as a practice and a technology?

The materiality of the manuscript, abolished by the digital nature of the original, is replaced as symbolic value by the flickering of the screen, its sleeplessness (proof of physical deterioration), and the possibility of a sudden computer crash.

Chejfec: What I find most intriguing in digital writing (in this case I refer specifically to literary writing on a digital screen) is the replacement of a “symbolic value” that would have been present if that text had been written on paper. The materiality of the manuscript, abolished by the digital nature of the original, is replaced as symbolic value by the flickering of the screen, its sleeplessness (proof of physical deterioration), and the possibility of a sudden computer crash. I mean, it’s a point of view, without any theoretical prerogative. It interests me as a metaphor of the literary condition of the manuscript, which must always exist as a deep awareness of the text. Digital writing takes on the plastic rites of manual writing in a much more literal way than mechanical writing. In fact, it is the most absorbing form of writing, because its immaterial condition makes the idea of manuscript abstract, and with it projects onto literature an idea of unreality that it always had but writers strove to controvert.

The Kochi Biennale installation consisted in transferring the material fragility of every manuscript (a manuscript is always unstable and especially fragile) to a surface that may be called antipodal, since walls are examples of permanence. Paradoxically, this makes writing more provisional, since its object has inevitably a shorter and more precarious life. However, I understand that in this case the dialogue is with the book as both format and surface. If you look at some of Anselm Kiefer’s books, you can see that the idea of a book works there as a support for images that, in the artist’s conception, can only be perceived if one takes into account their impossibility as books—books that are impossible to reproduce, impossible to carry, or impossible to handle; books that obliterate the idea itself of a book. Kiefer translates such an idea into a pictorial support; but obviously they are still books, which turn the giant shelves on which they accumulate into immense bookish installations. It occurs to me that some of the distrust of the traditional book that I think I see in his work convinced me that the idea of writing Baroni on the walls of Kochi was not entirely misconceived.

June 2018