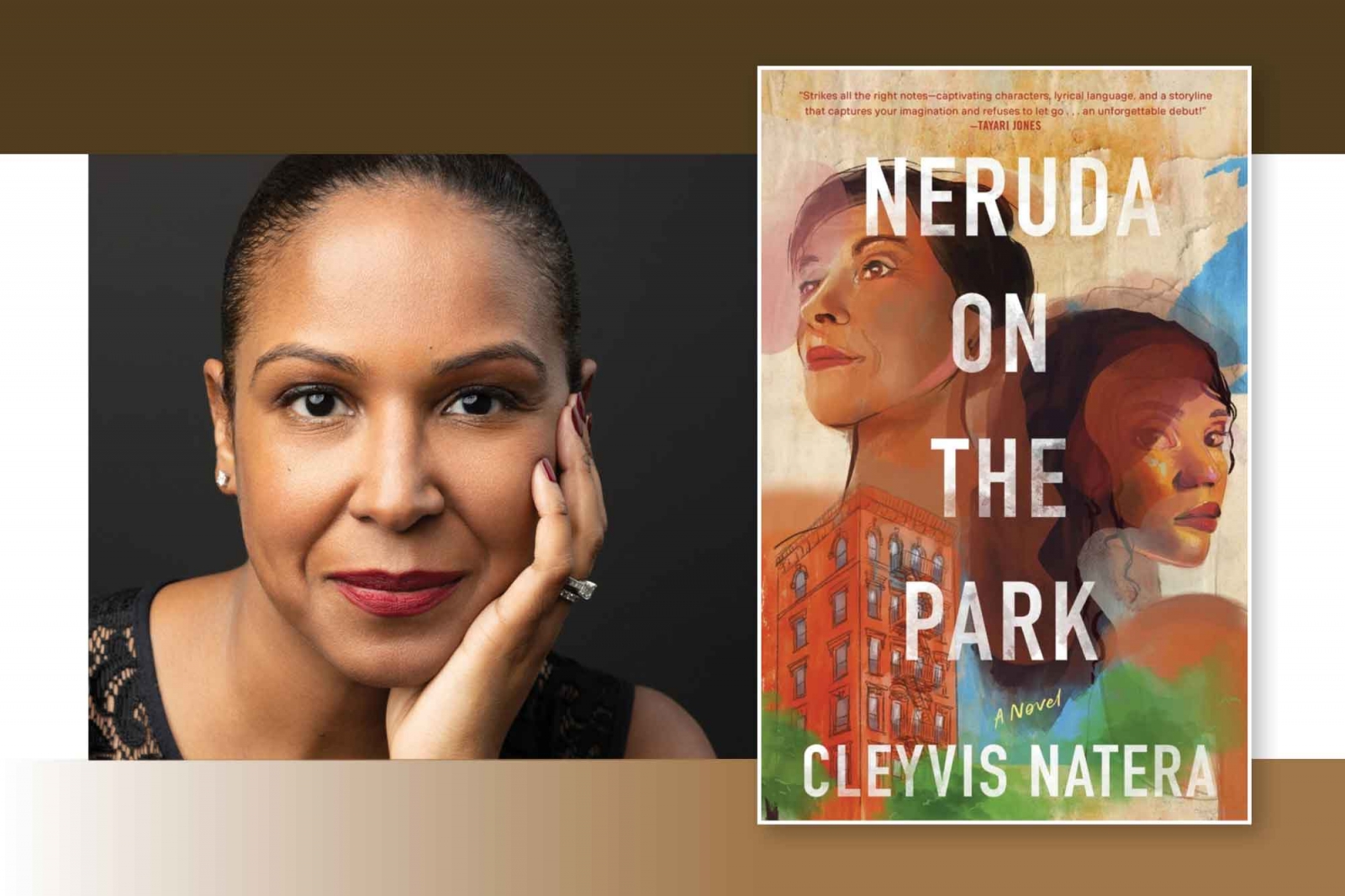

5 Questions for Cleyvis Natera

In Neruda on the Park, Cleyvis Natera’s debut novel, a young lawyer seeks a new path after being fired from a top law firm while her mother schemes to stop a development project in their predominantly Dominican neighborhood in New York City and her father makes plans for the couple to return to the Dominican Republic.

Q

A book of Neruda poems reappears throughout the story. Why Neruda?

A

Pablo Neruda is a beloved and polarizing figure in literature. I have always been fascinated by his work and the strength of his position as a cultural phenomenon. He wrote some of the most beautiful poems I’ve ever read, and the strength of his art is reflected in its resonance to this day, forty-nine years after his death. Neruda believed that art—especially poetry and literature—should be accessible to all members of society, regardless of class or education level. He was known for standing up for the rights of marginalized people against unjust governments. Yet he admitted to sexually assaulting a woman—a fact that is often dismissed or conveniently forgotten when we celebrate his achievements as an artist outside his country of birth. In Chile, there has been resistance whenever there is a movement to erect structures in his honor.

My debut novel, Neruda on the Park, introduces readers to Nothar Park, a fictional neighborhood in northern Manhattan comprised predominantly of a Dominican immigrant community on the cusp of great change. The gentrification that has altered neighborhoods all around New York City has somehow missed this community. The plot revolves around how my two main characters—mother-daughter duo Eusebia and Luz—react once the gentrification of the neighborhood arrives. While Luz, a young upwardly mobile lawyer, sees the coming change as inevitable, her mother, Eusebia, sees it as an opportunity to resist.

In Neruda on the Park, there are several characters who deeply love Neruda’s work. Luz’s parents, Eusebia and Vladimir, credit the love poems of Neruda with salvaging their struggling marriage by enabling them to articulate emotions they were unable to say aloud to each other. Likewise, Neruda’s work features prominently in a budding love affair between Luz and Hudson, the developer of the luxury condominium her mother so vehemently opposes. When Luz has an opportunity to help Hudson name the new structure he is building, she naturally proposes Neruda on the Park since the poet was responsible for saving her parents’ marriage and enabling her family to make the fictional neighborhood of Nothar Park home.

But there is also something more nuanced at play with the use of Neruda’s poetry throughout the novel—Neruda on the Park, as a construction, is the looming threat against safety for vulnerable members of this community—most notably the women who take center stage in this narrative. Central themes in my novel include womanhood and trauma, so I thought Neruda would serve as a solid departure point to allow for conversations about how we, as a society, deal with toxic figures who have contributed stunning and important works of art.

Q

This novel, with its multiple conflicts, is a page-turner. Gentrification is one central conflict. What other literature concerning gentrification would you recommend?

A

Halsey Street, by Naima Coster, is the brilliant story of Penelope Grand, a young woman who is forced to return home to Brooklyn to look after her ailing father. A struggling artist who has been unable to find firm ground, Penelope’s fraught relationship with her mother mirrors the devastation she must confront in her altered, gentrified Brooklyn neighborhood. There is a blindness, a refusal to confront the truth, that at times seems to shroud the way everyone functions in Coster’s fictional world, and it is within that space—where transformation is tied to a need to come to terms with the world and people as they truly are—that readers are granted a path to meditate on our own everyday fictions. Halsey Street is a virtuosic novel everyone should read to better understand themselves.

Survival Math, by Mitchell S. Jackson, is a spellbinding, powerful, and complex essay collection that tackles race, poverty, and violence in Jackson’s life. Documenting the ways in which he and members of his family had to navigate life-and-death decisions for survival in the streets of Portland, Oregon, Jackson delivers a true-to-life portrayal of many tragic truths in America. Paramount is this: very little adds up when it comes to a society that refuses to reckon with its own brutal calculations of who is worthy of the best chances at a good life.

Olga Dies Dreaming, by Xochitl Gonzalez, is a stunning debut about a family in crisis. Olga, an Ivy League–educated woman, has landed in an unusual profession that forever disappoints her revolutionary mother: pandering to the needs of the ultrarich as a wedding planner, while her brother, Prieto, serves the community as a congressman in a gentrifying neighborhood in Brooklyn. With tenderness and an unwavering narrative gaze, Gonzalez showcases how each of her main characters is forever compromising who they are to achieve success. Gonzalez turns the concept of the American Dream on its head. No one can achieve personal liberation when what society requires is complete surrender to fit in.

Such Big Dreams, by Reema Patel, follows Rakhi, a young woman who is coming of age in Mumbai. This ambitious debut tackles big themes like class, displacement, and the longing for home and community while rooting the narrative in a compelling, singular, and funny protagonist. Patel is a remarkable novelist who can call out issues of displacement, hypocrisy, and the white-savior complex with a steady gaze that forces deep contemplation and collapses the borders between nations grappling with similar issues of displacement and gentrification. Though we may think the issues of gentrification are singular to American cities, in this book we see how displacement is a global crisis.

Big Girl, by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, is the story of Malaya Clondon, an overweight, queer Black girl coming of age in Harlem’s gentrifying neighborhood in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Sullivan’s prose is achingly beautiful, and this book reveals the cost of a shifting landscape to its inhabitants with haunting and lyrical prose. This novel is also a love letter to a Harlem that no longer exists, and as someone who grew up in the neighborhood, it was simply stunning to see the way literature can archive, with brilliant clarity, the disappeared culture, histories, and vibrancy demolished by development.

Q

Is the work of fiction writing solely creative, or are there obligations that extend beyond the page?

A

I’m a firm believer that one of the reasons we see the dramatic increase in book banning across the United States in recent years—as tends to happen in most countries facing pointed attacks on human rights—is because literature has the potential to not only transform individuals but also alter society. It is because of our power to transform language and culture that literature is a tool for social transformation. I believe there is a clear obligation for the artist to have their work extend beyond writing for the act of creation to a responsibility toward meaningful influence over issues that plague our society: here, I speak explicitly of social justice and equality issues inclusive of the climate crisis, the ongoing attack on Black Americans and immigrants, women’s rights to autonomy, physical violence against members of the LGBTQIA community, and religious freedom.

Though some may argue it is impossible as an artist to engage our work in a meaningful way that can confront societal problems, I find that most artists impacted by social justice issues can’t help but bear witness, expose the truth, and demand change because our characters navigate worlds reflective of the real one—where those rights are constantly under attack. A good writer need not sacrifice excellence to expose the truth; I believe any work that lacks such honesty likely falters to meet the bar of greatness.

Q

You live in Montclair, New Jersey. Can you share a few favorite spots?

A

Watchung Booksellers is my favorite bookstore in Montclair. Owner Margot Sage-El and events director Kathryn Counsell have created a beautiful space that celebrates books and writers and the artists in our community with love.

For a delicious taste of outrageously good food, Samba Montclair, a Brazilian restaurant on Park Street, is the place to go. Get the acorn squash (which, even if not offered as a special, is often available!). It’s a shrimp dish in a rich coconut sauce mixed in with the most delicious spices. During the height of the pandemic, this dish helped me make it through some very difficult days.

Minia’s Montclair over on Lackawanna Plaza serves the best mangú con los tres golpes I’ve found outside of Washington Heights. It’s the place I go for Dominican comfort food when a drive to my mother’s apartment in Harlem isn’t possible.

Heather Carter recently opened an art space—Carter Fine Art Services—over on Park. It showcases exquisite visual art by both emerging and established artists as diverse as Montclair’s population. Every time I drop by Heather’s space, I am transported in the most phenomenal way!

Q

What have you been reading lately?

A

In Angie Cruz’s newest novel, How Not to Drown in a Glass of Water, we meet Cara Romero, an unemployed middle-aged Dominican woman who delivers a one-sided conversation with an unemployment counselor. Through a series of obligatory sessions meant to prepare and launch Cara back into the workforce, Cruz renders this complicated and flawed character in all her glory. It is in the precision of Cara’s struggle to earn a living, navigate complicated relationships with her queer son, manage the expectations of her friends, and juggle community demands against the need to embrace her full humanity that we see Cruz claim her own place as one our most important modern writers.

The Man Who Could Move Clouds, by Ingrid Rojas Contreras, is a memoir unlike any I have read before. In this structurally inventive book, Contreras allows readers to journey with her through the astounding history of her family’s legacy: an inherited ability to cure the ill, see the future, even—yes—move clouds. Though many may be struck by how Contreras leverages magical realism in this factual account of a family’s reckoning with the lasting effects of colonialism, what I loved most about this book is how Contreras weaves personal history in the context of historical events that showcases her gifts not only as a storyteller but an insightful cultural critic. Sentence by sentence, this is one of the most gorgeous memoirs I’ve read in years.

If I Survive You, by Jonathan Escoffery, is a blazing, astonishing feat. This collection of short stories follows an immigrant family who are forced to flee Jamaica due to violence and expect the United States to deliver as a promised land. Spoiler alert: it does not. Each story sheds light onto what it means to be part of an immigrant population often shut out of opportunities because of race and debunks the persistent myth that we live in a meritocracy. It also highlights how the forces of toxic masculinity and capitalism often mean access to progress is gained only by a willingness to stand on the carcass of what (and who) has been destroyed. Escoffery delivers such fresh, unexpected situations for his characters that I haven’t stopped thinking about them weeks after I put the book down.

The Town of Babylon, by Alejandro Varela, served so much queer badassery I had a difficult time tending to my everyday obligations. In this striking debut, Andrés, a gay Latinx professor, has returned home to care for his ailing father. This is a novel that delivers on a grand scale: Varela’s ability to defy conventions is what makes this novel sparkle. It is an ambitious, character-driven book that centers the life of a deeply principled man with deliciously flawed tendencies. Big themes like class, identity, and race are discussed head-on, and what we’re left with is a tender and haunting narrative that asks such pressing questions: Can one ever overcome the heartbreak of our first love? Is the brutal pain of immigration by our parents ever worth the outcome of upward mobility (if such mobility can ever be achieved)? I was charmed to find myself finishing this novel with a renewed sense of hope for what art can do to help us see the world.

Cleyvis Natera is the author of Neruda on the Park, a 2022 New York Times Editor’s Choice. Her short fiction, essays, and criticism have appeared in the New York Times Book Review, URSA, Alien Nation: 36 True Tales of Immigration, Brooklyn Rail, TIME, The Rumpus, Gagosian Quarterly, Washington Post, Kenyon Review, Aster(ix), and Kweli Journal, among other publications.