Memory as Resistance and Imagination: A Tribute to Boubacar Boris Diop

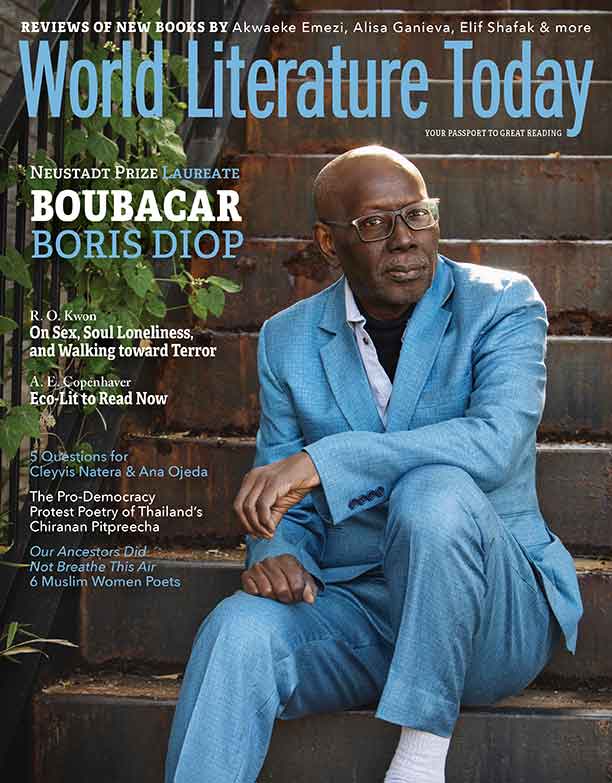

Jennifer Croft, who nominated Diop for the 2022 Neustadt Prize, delivered the following encomium at the ceremony during which he received the award at the University of Oklahoma.

In 2016 I was asked to serve as a judge for a small literary prize called the Best Translated Book Award. Each juror received around two hundred books. Not everybody read all, or even any, of these entries; I had just moved to a new city where I knew almost no one, and where I had nothing if not the time to read.

There were popular books and critical darlings, hipster underdogs with clever covers, titles that promised wisdom or adventure, books by authors I’d translated myself. Every once in a while, there was a book I couldn’t put into any category. One such book was a novel called Doomi Golo, by a man named Boubacar Boris Diop.

As soon as I started reading, I knew I had found my nomination for the prize. It was sweet and insightful, winsome and profound. It was a novel that felt like a friend, like a conversation over a glass of wine on a wobbly little table on a busy street that makes you feel like the world is filled with possibilities again, like every passerby shimmers with interest, and like the lights in the distance are a dazzling magic that might transform you into a more thoughtful, more feeling person—a person able to pay attention again.

Doomi Golo felt like a friend, like a conversation over a glass of wine on a wobbly little table on a busy street that makes you feel like the world is filled with possibilities again.

Alas, that book was not the winner of the Best Translated Book Award. Perhaps in an effort to compensate for my failure to persuade my fellow jurors, I tracked down the brilliant translator of Doomi Golo and began an interview with her over email. But over time, and at a distance, that interview fizzled and was never finished or published. I made friends in my new city and got married; I wrote my own books. Years passed, and I kept my marked-up copy of Doomi Golo on the bookshelf in the bedroom of wherever I lived as my husband (another Boris) and I moved to newer cities still. I also read some of the author’s other works, and I discovered that they were all as great as Doomi Golo, each in its own ambitious, warm way. In 2020, when I was asked to nominate an author for a big prize called the Neustadt, my selection was immediately obvious to me.

“Fiction is an act of rupture”—writes Diop in an essay entitled “Write and . . . Keep Quiet”—“in that it brings the conflicts and failures of a social group to the surface, rather than trying to conceal them. The writer is, by definition, a traitor. That also means he is a being of pure love.” Diop is not only a preeminent writer of fiction and nonfiction but a preeminent activist, too. He co-founded Senegal’s first independent daily paper and served as editor in chief of another Dakar news source. He co-owns a bookshop in Dakar that hosts events and debates; he co-founded a publishing house and launched a new imprint at another house that publishes world literature translated into Wolof.

His brilliant critiques of colonial and postcolonial violence have changed the way we think about the twentieth century as well as our own. Toni Morrison called his novel about the Rwandan genocide, Murambi: The Book of Bones, “a miracle.” Murambi was a turning point in Diop’s career; he articulated his literary project with urgency and lucidity in a subsequent essay entitled “Transforming Genocide into Art”:

While the delirious cruelty of the perpetrators of this genocide is difficult to comprehend, it is not as senseless as one might think. By humiliating these innocent people before cutting them up with a machete, the killers wanted to convince themselves and especially their victims that they were not really human and that nature had erred by putting them on this earth. That may be why the denialists are always slightly taken aback when one holds up the evidence of facts and figures for them to see. In their view, nobody died, because the people we are making such a fuss about never had the right to exist in the first place. This is why writing fiction is an excellent way of opposing the genocidaire and his machinations. It gives the victims a soul, and, even if it does not resuscitate them, it at least gives them back their humanity through the ritual of mourning.

Diop’s oeuvre foregrounds memory as resistance and imagination as a revitalizing, rehumanizing force.

Diop’s oeuvre foregrounds memory as resistance and imagination as a revitalizing, rehumanizing force. He deserves every prize. In the words of Doomi Golo’s exceptionally gifted translator, Vera Wülfing-Leckie—who would have been thrilled to be here with us today but who died tragically at the start of the pandemic—the message of Diop’s work “is certainly salient for readers in many countries right now—potentially brutal political forces are rising to the surface in many places, and many of the rights and freedoms people have fought and died for over many decades are seriously at risk.”

I am beyond honored, and deeply delighted, to present this year’s Neustadt Prize to Boubacar Boris Diop.

Tulsa, Oklahoma