African Cinema’s Alternative Archives and Boubacar Boris Diop’s Doomi Golo

Boubacar Boris Diop’s novel Doomi Golo is a rich puzzle of personal and historical narratives on the dilemma of postcolonial identity and futures. The following essay traces many of the novel’s cinematic, cultural, and political filiations.

Alternative Creative Afro-Archives

Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy’s “Report on the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics” (2018) proposed a new approach to the future of the colonial past, noting that Africa should reinvent itself through a synthesis of traditional and contemporary forms of social organization and cultural expressions. Referencing his book Afrotopia: The Future Is Open (2019), Felwine Sarr defines the new epistemological paradigm of the archive:

My basic idea is that the future is open. That she remains open to all of us. And that it is the task of Africans to think and formulate their own future and to find their own metaphors for it. . . . Afrotopia wants to open new ways of thinking of the social, the economic, and the political realms, and of humanity itself. (“Afrotopia”)

While the momentum grows concerning the postcolonial afterlives of cultural objects, the need for a more general rethinking of the archive is needed—a restitution of alternative or Afro-archives. The Nairobi-based cultural critic Patrick Gathara argues that “the path to colonial reckoning is through archives, not museums”—such as through the creative archives of fiction, film, or music.

The creative archives of African cinema have played a crucial role in preserving history and imagining alternative futures.

The creative archives of African cinema have played a crucial role in preserving history and imagining alternative futures. The Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, often called the “father of African cinema,” noted the importance of visual storytelling:

I think cinema is needed throughout Africa because we are lagging behind in the knowledge of our own history. I think we need to create a culture that is our own. I think that images are very fascinating and very important to that end. But right now, cinema is only in the hands of film-makers because most of our leaders are afraid of cinema. (“Ousmane Sembène”)

Sembène used fiction and film to correct the omissions of colonial archives, as in his screenplay on Samori Touré or the French treatment of African soldiers in World War II in the film Camp de Thiaroye. His film Mandabi was the first film in an African language, its Wolof dialogue subtitled into French.

Jean-Pierre Bekolo of Cameroon is engaged in various mediums and film genres and is credited with directing the first science fiction film in Africa (Les Saignantes). He has also directed documentary films that combat colonial historical accounts. Bekolo’s films often use allegorical representations to comment on African politics. He employs the power of cinema to reimagine life on the continent:

I am a filmmaker. In thinking about the future, I wonder if cinema can redefine Africa’s future beyond the development perspectives of NGOs. Can cinema imagine our utopias and dystopias, and can it be the design lab for Africa’s reinvention? Resilience is something all Africans strive for. In achieving this, can Africa overcome death?[i]

Through his films and public advocacy, Bekolo offers alternative futures to dictatorial and neoliberal political and economic models. His films explore existential possibilities for “human” as opposed to “naked life” where the state’s role should be “to protect life”:

Africans need a Leviathan, a state where an African can give mandate to a representative to represent him in the sense that his life is not threatened, and if needs be revoke that mandate if he feels that his life is in danger. ... One may think that this utopian state doesn’t exist, but it has been named, visualized, sung and written about so many times by artists, writers and political leaders in various mediums. (“Haunted by the Future” 118–21)

Bekolo calls post-independence “the birth of dystopia” with imagined alternatives elsewhere: “All these incapacities have produced a new utopia in the mind of some Africans: the white man’s country.” For Bekolo, cinema offers “another utopia,” what he calls the “art of living,” defined by narratives of imagination that “will command us to change our lives.” For Bekolo, visual stories are transformative: “African cinema, our cinema, is capable of organizing a necessary reset, and is capable of being a leader in the reinvention of another way of living, of leading us to a utopia where we have exited capitalism.”[ii]

Didier Awadi is a Senegalese musician who uses music as well as film to create alternative historical archives. Awadi dedicates his hip-hop album African Presidents (2010) to Africa’s founding fathers and influential thinkers from the diaspora. The project is an oral archive of famous speeches sampled in song. Awadi comments on his album: “What we’re trying to do, as musicians and not historians, is rewrite the past.” He describes his songs as “the pieces of the puzzle that is African history. . . . Africa is like a plane that’s crashed and we’ve just retrieved the black box containing all the information about the flight.” The album references such figures as the assassinated president of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara; Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who advocated for a United Africa; or such diasporic figures as Frantz Fanon and Malcolm X.

Awadi also produced a documentary film about the making of the hip-hop album as a form of visual “archive.” The film United States of Africa: Beyond Hip Hop (2013) takes Awadi through forty countries in search of information on African leaders, many assassinated by political foes. Awadi calls his archival recovery project the “lion’s” as opposed to the hunter’s story. His film The Lion’s Point of View (2011) pieces together the stories of African youth’s clandestine migration to Europe. The film looks for answers why young Africans would seek their futures in Europe: “Fifty years of independence. They promised us happiness and prosperity. Nowadays young Africans climb into simple wooden boats, they cross the desert and the sea toward Eldorado.”

Boubacar Boris Diop’s Doomi Golo: The Hidden Notebooks

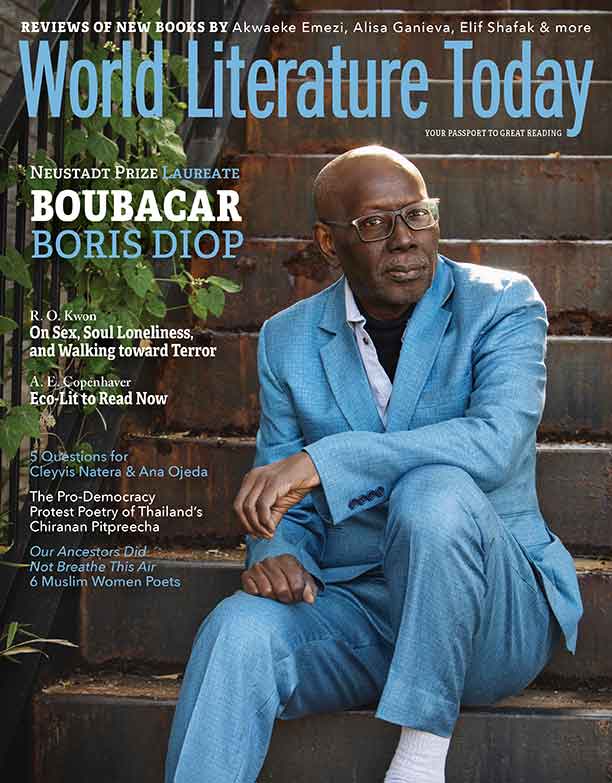

Diop’s novel—originally written in Wolof, then rewritten in French and translated into English—pays homage to African cinema, and its plot often references the films of Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambéty. As Boris Diop noted in a conversation with Bojana Coulibaly during the celebration of his awarding of the Neustadt Prize, while growing up in Dakar he spent much time in the ciné-clubs watching and discussing the films of African filmmakers, most notably the films of Ousmane Sembène (October 25, 2022, University of Oklahoma). The community discussions of literature and film allowed for an expression of moving reality. He read the books of Mongo Beti, Cheikh Anta Diop, Ousmane Sembène, Aimé Césaire, and Frantz Fanon but also of John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Gabriel García Márquez, whose writings influenced his own storytelling and the commitment to social change through the power of the arts—the duty of memory.

Doomi Golo mourns the brain-drain of Africa’s youth to Europe, a tragic wave of economic flight that leaves a generation disconnected.

Doomi Golo is the memoir of the main character Nguirane Faye Tall, written for his grandson Badou, who left Senegal—possibly for Europe, the place Nguirane calls “over there.” The story focuses on Badou’s parents: his father, Assane Faye Tall, who migrated to Marseilles to be a footballer; the wife he left behind (Bigué Samb); his new French wife, Yacine Ndiaye; and their culturally alienated children (Mbissine and Mbissane, also called Ninki-Nanka in Nguirane’s nightmare). The novel mourns the brain-drain of Africa’s youth to Europe, a tragic wave of economic flight that leaves a generation disconnected. The title of the book, Doomi Golo, translates from Wolof as the “children of the monkey,” which references both the original meaning for golo, the sly and greedy trickster figure of the monkey, but also the racist epitaph for Africans in Europe. The title refers to Assane Tall’s French African wife, Yacine Ndiaye, and their children born in Marseilles—their total cultural alienation from their home and familial roots. Their disconnection makes them unrecognizable as human to their family in Senegal, thereby flipping the epitaph for “whites” or Toubabs (Wolof for whites or foreigners) by Africans. The novel is a tale of warning about losing connections to place, family, ancestry, language, and culture.

The disjointed narrative traverses several hundred years of history from the founding of the Wolof Empire (in 1350), the secession of Cayor (in 1549), French colonization (in 1879), then independence (in 1960) through the present. Nguirane Faye’s story moves back and forth between the present, the recent and distant pasts, where time folds onto itself and generations connect. Diop punctuates the nonlinear narrative with precolonial Wolof Njaay’s proverbs, such as:

Even if you are dying of thirst, never drink water from the sewers. The day will come when rain will fall in abundance from the sky and then you won’t be proud of yourself. (94)

The novel also tells an alternative history of African revolutionaries, many assassinated by European or local foes:

Cheikh Anta Diop. Amilcar Cabral. Mongo Beti. Samory Touré. Thomas Sankara. Lumumba. You know all those names. Each one of them was a Man of Defiance in his own right, and for that reason and for that reason alone, the white colonizer killed them or at least reduced them to silence. (130)

Diop pays homage to the heroes of African political and cultural independence:

I know, I know—you are telling yourselves that all he had to do was to keep his mouth shut, Lumumba, since this is what happens to a black man who oversteps the mark.

You are spitting your venom.

He was just playing the hero, you think. Too bad for him.

That’s what happens when an egg bashes its head against an iron door!

That is how Wolof Njaay puts it. (201)

The killing of Patrice Lumumba—twice—once by bullets, then the pieces of his body “dropped into a barrel of sulfuric acid” is described in emotional detail (199). Only two of Lumumba’s teeth remained, as they were kept as souvenirs by the attending Belgian police commissioner (200). Thus memories, souvenir objects, and absent bodies stand in for the missing archive. The story of Lumumba’s assassination is retold in Didier Awadi’s film United States of Africa: Beyond Hip Hop. Diop’s fiction, Awadi’s film and music memorialize Lumumba powerfully against the material souvenirs and his absent body. These texts—fiction, film, and music—create multimodal Afro-archives to correct the colonial erasures.

These texts—fiction, film, and music—create multimodal Afro-archives to correct the colonial erasures.

The author of The African Origin of Civilization (1974), Cheikh Anta Diop, makes several appearances in the novel as a model for “Africanity”—African dignity and honesty in political leadership:

Cheikh Anta Diop, on the other hand, has always walked a path that was completely straight. His supporters found it hard at times to live with that degree of moral rectitude, and that’s when he used to say to them, “There is never a valid reason to lie to those who have put their trust in us. The truth may hurt them, or even plunge them into despair, but at the end of the day it makes us stronger.” (137)

Cheikh Anta Diop often reaches legendary proportions in the novel; his words echo Wolof Njaay’s proverbs. The mythical character of Ali Kaboye, who takes over as narrator after Nguirane Faye’s death, recalls the precolonial heroism of young men in an imagined conversation with Badou:

I am still shaken by it. I encountered a group of proud and joyful young men who had their hair braided in the traditional style and were wearing long beaded necklaces and copper bracelets. Everything about them radiated vigor. Their gait was supple and resolute, reminiscent of the ceddo of old going to war. And I, Ali Kaboye, stared at them in amazement, since the gestures and the gaze of each of them said to me. I am African, I am black, and no matter what anybody might say, that’s the most marvelous thing in the world.

Yes, it was Cheikh Anta Diop who taught us to look at ourselves in the mirror without shame. (198)

The novel ponders the tragic consequences of colonial shame: “Being ashamed of oneself can have extremely tragic consequences”—a lesson Nguirane learns when he travels to the assumed village of his ancestor Mame Ngor (65).

The chapter references Sembène’s 1976 film Ceddo (The Outsiders, i.e., non-Muslims). The film was banned in Senegal, and copies are still difficult to find. The film focuses on the conflict between traditional ways of life and the encroachments of Islam, Christianity, and European colonialism. The story addresses the question of lineage: who should succeed the king. It concludes with a dramatic scene, where the victorious imam who forcefully converted the Ceddo to Islam is killed by Dior Yacine, the king’s daughter, with a rifle traded for slaves. The final close-up freezes on Dior Yacine and ends abruptly. In an interview Sembène explains:

Often in Africa it’s only the men who speak, but one forgets the role, interest of women. I think the princess is the incarnation of modern Africa. . . . There can be no development in Africa if women are left out of the account. (Interview with Ulrich Gregor).

Diop’s novel opens with a dedication and inscription in “Part 1: Nguirane Faye”: “Shame on the nation that doesn’t listen to its little girls.” The theme of shame is often addressed throughout the novel (e.g., colonial shame in the loss of language, culture, or dignity; the shame of giving birth out of wedlock; the shame of not knowing one’s ancestry; or the lack of shame for sexual impropriety and disrespectful behavior, which characterizes Yacine Ndiaye, the “she-monkey” of the title). The inscription celebrates women and girls against the values of traditional patriarchy. Djibril Diop Mambéty’s last film, The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1999), is the story of Sili, a young disabled girl, who decides to help her grandmother by joining the street boys to sell the newspaper The Sun. Sili’s character is a triumph of daring to imagine a different world that does not judge by ability, age, gender, or social class. Mambéty dedicated his film career to the “the little people” of society, whom Sembène called God’s Bits of Wood (novel, 1960). The film is part of a trilogy, preceded by the film Le Franc—with the third segment never finished due to Mambéty’s untimely death from cancer.

Perhaps Nguirane’s grandson Badou is named after Mambéty’s second film, Badou Boy (1970). The short film is a sarcastic look at post-independence life in Dakar and follows the adventures of what the director described as a “somewhat immoral street urchin who is very much like myself.” The film is set against the backdrop of a bustling Dakar in the late 1960s where a “Cop” believes “Badou Boy” is a menace to society. Badou leads the “Cop” on a chase through the shantytowns to the center of Dakar. A similar spatial trajectory is depicted in Sembène’s Borom Sarret (Cart Driver) (1963). The films and the novel cross-reference each other, elevating the stories to the credibility of the archive.

The character of Ousmane Sow, modeled on Sembène, appears several times in the novel through encounters with Nguirane Faye. Diop retells the plot of Sembène’s Borom Sarret, which follows a cart driver through his day in Dakar. Ousmane Sow’s character appears first in “Notebook 1: The Tale of the Ashes”:

When I hear little bells jingling through the silent dawn, I know Ousmane Sow, the cart driver, is harnessing his horse Tumaini, right around the corner of our sand-blown street. . . . One day I question him about the meaning of his horse’s name. “Tumaini means ‘to hope’ in Swahili,” he replied as he fixed me with his open, intelligent gaze. “So if you hear this word in countries like Tanzania, Rwanda or Kenya, Nguirane, be aware that it means ‘to hope.’” (23)

In the retelling of the film in the novel, Diop makes Sembène a character and changes the name of the horse from “Albourah” to the Swahili word “Tumaini,” giving it a larger pan-African reach and a meaning of inspiration.

Cinema is a constant theme in Diop’s novel, from references to African cinema’s iconic films by Sembène and Mambéty to movie theaters in Dakar.

Cinema is a constant theme in the novel, from references to African cinema’s iconic films by Sembène and Mambéty to movie theaters in Dakar, such as the El Malick cinema where the French ex-pat Maurice Jacquin had his hall for the reinvented wrestling matches with punches that turned Senegalese traditional wrestling or Laamb into a commercial and brutal spectacle, as discussed in “Notebook 5: Brief Escapades” (131). Or the Palace cinema, which showed foreign films:

A giant poster with the words “Apache Fury” shows some Indians wearing brightly colored feather headdresses and fighting American soldiers at the foot of a hill, their horses are rearing and trampling on the dozens of bodies that are lying scattered on the ground. (94)

The two French children, Mbissine and Mbissane (Ninki-Nanka), watch violent French war films on TV, the volume turned up so loud that it drives their grandfather mad (119–20).

References to iconic African films that punctuate the novel counter the loud, violent, and immodest foreign films encroaching on public culture. To the she-monkey character of Yacine Ndiaye, the novel counterposes the love story of Nguirane and Faat Kiné, whom he calls “The woman I have loved” in “Notebook 3: Playing in the Dark” (181). Fatou or Faat Kiné is also the heroine of Sembène’s Faat Kiné (2000) about an independent female character who defies the stigma of unwed motherhood and becomes a successful businesswoman in a male-dominated society. Fatou’s character in the novel is an orphan who was abandoned by her mother:

Faat Kiné tended to be a very serious and thoughtful person at the best of times, but that night, she seemed more preoccupied than usual.

I am concerned. “What is the matter, Fatou?”

After a brief silence, she calmly replies, “The truth is, Nguirane, that I feel like I have never had either a father or a mother.”

After she was born, her mother took her into the bush in order to kill her. But someone surprised her while she was digging a hole near a shrub and she fled, leaving the newborn behind.

For a long time, Faat Kiné believed she was the daughter of the people who had taken her in, but they eventually thought they should tell her the truth about her own history. (183)

The story of Faat Kiné the orphan in Diop’s novel also echoes another of Sembène’s films, Niaye (1964), a short film that followed Borom Sarret. The film addresses topics such as incest, suicide, and patricide: the story takes place in a village where the chief impregnates his daughter, who intends to leave her baby in the bush; instead, she leaves the village with the baby in her arms.

The novel closes with another reference to Sembène’s film Guelwaar (1993). The story focuses on a mishap: a Catholic and a Muslim die on the same day, but due to administrative error, the relatives of the Muslim man get the body of the Christian whose family must settle for an empty casket. The film addresses issues of economic development though foreign aid and debt and interreligious tensions. In a memorable scene, Guelwaar recites a verse by Kocc Barma Fall, the seventeenth-century Senegambian philosopher and lamane. Diop’s novel often cites Kocc Barma Fall, who represents the voice of wisdom and defiance:

There is only one way to describe him: impossible to pin down. He looks at you with his small, inquisitive eyes and his mischievous smile jumbles up all your emotions, a smile that always seems to say, I see right through you, you can’t lie to me. The truth is that nobody ever really feels at ease with him. . . . Challenging the overlords is his favorite pastime. When there is an audience at the court of the Damel, Kocc Barma always waits until the last moment before getting up to speak. We all listen to him with bated breath, because even the smartest among us never know what he is going to say. In fact, his general formula seems to be: I disagree with everything I have just heard, including what came out of the Damel’s very own mouth! That is the true extent of the Kocc Barma Fall’s recklessness. He makes no distinction whatsoever between the Damel himself and me, Ali Kaboye, a simple dignitary of the Cayor. (210)

In Sembène’s film, Guelwaar’s character channels the philosopher Kocc Barma Fall but also his twentieth-century incarnation in Thomas Sankara, the charismatic president of Burkina Faso (1983–87). In the film, the character Guelwaar makes a speech about economic self-reliance in front of a USAID banner, rejecting dependence on foreign aid. Thomas Sankara’s famous last speech to the Organization of African Unity on July 29, 1987, in Addis Ababa called for a collective refusal to pay African debts to international imperialist powers. He predicted if other African nations wouldn’t join him and Burkina Faso in refusing to continue paying their foreign debts, he wouldn’t be alive to attend the next meeting—a prediction that proved to be true: he was assassinated by French, US, and local interests on October 15, 1987. In an October 4, 1984, speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations, Sankara explained:

The truth about aid, represented as the panacea for all ills and often praised beyond all rhyme or reason, has been revealed. Very few countries have been so inundated with aid of all kinds as has mine.

Aid is supposed to help development, but one can look in vain in what used to be Upper Volta to see any sign of any kind of development. The people who were in power through either naivety or class selfishness could not or else did not want to gain control over this inflow from the outside or grasp the scope of it and use it in the interests of our people.

Diop’s novel is a rich puzzle of personal and historical narratives on the dilemma of postcolonial identity and futures.

University of Oklahoma

Works Cited

Awadi, Didier. Les États-Unis d’Afrique: au-delà du hip hop. [Montréal]: National Film Board of Canada, 2013.

———. Le point de vue du lion. Senegal: AfricAvenir, 2011.

———. Présidents d’Afrique. [Montréal]: Périphéria, 2010.

Diop, Boubacar Boris. Doomi Golo: The Hidden Notebooks. Trans. Vera Wülfing-Leckie & El Hadji Moustapha Diop. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2016.

Diop, Boubacar Boris, and Bojana Coulibaly. “A Conversation about Writing Africa.” Norman, Oklahoma, October 25, 2022, YouTube.

Harrow, Kenneth W. “Monkeys from Hell, Toubabs in Africa.” In African Migration Narratives: Politics, Race, and Space, edited by Cajetan Iheka and Jack Taylor, 203–21. University of Rochester Press, 2018.

Heidendreich-Seleme, Lien, and Sean O’Toole, eds. African Futures: Thinking about the Future through Word and Image. Bielefeld, Germany: Kerber, 2016.

Sankara, Thomas. “Burkina Faso President Thomas Sankara’s ‘Against Debt’ Speech 1987 Part 1.” YouTube.

———. “Speech before the General Assembly of the United Nations.” October 4, 1984. Marxists Internet Archive, 2019.

Sarr, Felwine. Afrotopia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

———. “Afrotopia or The Future Is Open.” Interview with Deniz Utlu. Schloss-Post, April 30, 2019.

———. “Es ist an der Zeit, dass Europa zuhört.” Interview with Deniz Utlu. Der Freitag, May 2019.

Savoy, Bénédicte, and Felwine Sarr. “The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics.” Report, November 2018.

Sembène, Ousmane. Interview with Bonnie Greer. The Guardian, June 5, 2005.

———. Interview with Ulrich Gregor. Framework nos. 7/8 (Spring 1978).