Hero Blues: Bob Dylan’s Philosophy Twists Popular Song

Throughout his sixty-year-plus career, Bob Dylan has combined an “incredible skill with a wildness of spirit,” as magician Penn Jillette recently put it. He towers above others—Bruce Springsteen, John Prine, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell—through volume, range, and brash unpredictability. In the past decade he has retooled Frank Sinatra crooning (Triplicate) and wrung suspicious reverie from Covid crazy (Rough and Rowdy Ways). In this latest book, he submits essays on sixty-six recordings, having his say about cherished records in a voice that favors wildness over skill.

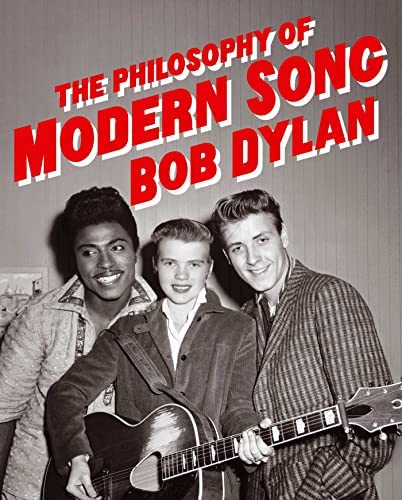

Dylan has great ears and great taste: he spotlights many performers who don’t get enough credit and rescues others from silence. But his off-the-cuff style inadvertently reveals a reactionary sensibility and undercuts his credibility. Framed by photographs chosen by Parker Fishel and David Beal, in a plush design by Coco Shinomiya, the layout seems both overliteral and didactically allusive. It’s this season’s Drunk-Uncle Coffee-Table Item, designed for display.

Dylan has great ears and great taste: he spotlights many performers who don’t get enough credit and rescues others from silence. But his off-the-cuff style inadvertently reveals a reactionary sensibility and undercuts his credibility. Framed by photographs chosen by Parker Fishel and David Beal, in a plush design by Coco Shinomiya, the layout seems both overliteral and didactically allusive. It’s this season’s Drunk-Uncle Coffee-Table Item, designed for display.

Clichés pile up and ricochet off one another, with the occasional flicker of light. In describing “Nelly Was a Lady,” by Alvin Youngblood Hart, Dylan writes: “In this song the fire’s gone out and your life is missing,” a turn that echoes his best critic, Greil Marcus. (In fact, skip this title in favor of Marcus’s Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs.) Hank Snow’s “I Don’t Hurt Anymore” will “tear your heart out”; “Feel So Good,” by Sonny Burgess, comprises “the sound that made America great.” Some platitudes explode into shrapnel (applause for “a hallucinogenic amalgamation of succubus and thaumaturge”) but not often enough to justify the logorrhea. With a rock band behind him, guessing at where he’ll land, Dylan’s lyrics can prove wildly entertaining: fencing with meaning, spinning language into twaddle at a furious rate, his performances give the ear a wild ride even in slower numbers.

As prose, most of this blurs into wobbly beatnik squawk. About Pete Townshend’s “My Generation,” Dylan writes: “People are trying to slap you around, slap you in the face, vilify you. . . . They don’t like you because you pull out all the stops and go for broke. . . . They give you frosty looks and they’ve had enough of you, and there’s a million others just like you, multiplying every day.” A little of this goes on far too long. In song, Dylan twists clichés with a snap or a snarl; here they just crowd into one another. For pages on end, his style turns mannered. What works as scattershot vocal delivery doesn’t translate into prose. What’s worse, he solved this problem in Chronicles: Volume 1, his absorbing 2004 “memoir,” which this effort somehow diminishes.

Dylan doesn’t respect the experience of reading the way he does the experience of listening.

Dylan doesn’t respect the experience of reading the way he does the experience of listening. Some sequences toss up unexpected meanings, like the way Johnnie and Jack’s “Poison Love” follows the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion,” or how Rosemary Clooney’s “Come on-a My House” provides comic relief after Jimmy Webb’s “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” (no mention of Glen Campbell, a slight). But overall, Dylan avoids building many of his ideas—he tosses them out as if they’re gold coins. He starts with Bobby Bare’s “Detroit City” and ends with Dion and the Belmonts’ version of “Where or When,” but randomize the essay order any which way and you’ll get much the same effect.

Many ideas collapse into hyperbole. “The greatest of the prayer songs is ‘The Lord’s Prayer.’ None of these [other] songs even come close,” Dylan writes. He calls Tony Williams, the euphoric vocalist from the Platters, “one of the greatest singers ever. Everybody talks about how Sam Cooke came out of gospel to go into the pop field. But there’s nobody that beats this guy.” Dylan does this repeatedly for emphasis (Jackson Browne’s “greatest song,” or Sonny Bono’s “greatest achievement”). But this Williams essay crashes into an iceberg of bad taste, “[Williams] took his spirituality with him into the pop world. You couldn’t picture this guy getting shot, bare-naked in a motel room.” Presumably, Dylan judges Sam Cooke’s records by his unseemly murder, which the rest us of call blaming the victim.

In other places, Dylan makes reductive comparisons: “Little Walter is an excellent guitar player and . . . a greater singer than anyone on Chess Records. But he also turns in what is perhaps the deepest vocal in the whole Chess catalog on the song ‘Last Night.’” Dylan can’t stop, or get out of his own way: “Out of all the artists on Chess he might have been the only one with real substance.” Any discerning editor would have counseled the writer not to undermine his own enthusiasm. Lumping these great Chess iconoclasts together (Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon . . .) reduces them all.

Predictably, since his catalog sports very few female narrators (any female narrators?), Dylan writes weakly about women. Ever since the put-downs in “Just Like a Woman” and on through “Don’t Fall Apart on Me Tonight” and “Is Your Love in Vain?”, Dylan has veiled his misogyny by “keeping things vague” (to quote Joan Baez).

Not here. In this passage on 1975’s “Witchy Woman,” a third-rate Eagles song by Don Henley and Bernie Leadon, he writes, “The progressive woman—youthful, whimsical, and grotesque. The woman from the global village of nowhere—destroyer of cultures, traditions, identities and deities.”

But even this gets overtaken by Dylan’s disdain for divorce lawyers. In his essay on Johnnie Taylor’s 1973 hit “Cheaper to Keep Her,” he blames these figures for “teen suicides and serial killers. . . . They are, by definition, in the destruction business—they destroy families.” His complaints about alimony build to a surreal passage on polygamy: “No one has fought for the only one that really counts, the polygamist marriage.”

Dylan, the Malibu rock star, rides the victim carousel. Then he grasps for a lifeline: “And . . . when did I ever posit that the polygamist marriage had to be male singular female plural? Have at it, ladies. There’s another glass ceiling for you to break.” As if that’s what liberation looks like. In a country where one in three women experience rape or sexual violence, Dylan descends from his mountaintop with the solution: what marriage needs is more men.

The many glaring omissions here count as a feature, not a bug. Joan Baez goes unmentioned. He brings up Joni Mitchell twice but only in passing: first, in relation to the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, in relation to their guitar style (“[He] has his own style, not unlike Joni Mitchell but from a different place”); second, in a surface reading of her song “The Circle Game,” not a complete essay. Other missing females, many of whom have celebrated Dylan interpretations, include Janis Joplin, Rosanne Cash, pj harvey, Sheryl Crow, Emmylou Harris, Christine Collister, Patti Smith, Bonnie Raitt, Tracy Chapman, Chrissie Hynde, Etta James, Aretha Franklin, Sally Timms, Neko Case, Jenny Lewis, Bettye Lavette, and Tina Turner. Special shout-out to Sinéad O’Connor, who got booed off his stage at the thirtieth-anniversary celebration, unmentioned by Dylan since that 1992 incident.

Many male peers also go missing. After a decades-long friendship with George Harrison, only Roy Orbison from the Traveling Wilburys gets the nod (“Blue Bayou”). He mentions a few Lennon-McCartney songs (“The Fool on the Hill,” “Give Peace a Chance,” and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)”) but doesn’t devote an essay to any, or to anything by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. He seems more generous toward the dead (like Warren Zevon) than the living (Bruce Springsteen, Brian Wilson, Stevie Wonder, Bryan Ferry, David Byrne, or Beck—nothing for Leonard Cohen, T. Bone Burnett, Richard Thompson, Tom Waits, Lou Reed, Dwight Yoakam, John Hiatt, and Neil Young). Paul Simon earns special rebuke: Dylan goes into detail about how “American Tune” borrows material from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, without mentioning Simon by name.

Perhaps because Dylan’s approach feels studiously informal, some of the lesser material gets some of the better prose. His extended riff on “Volare” overtakes the song itself: “The vocal is all about dynamics—one moment soft whispers of intimacy, the next joyous exultation, an interlude of recitation followed by wistfulness that translates without language.”

Other phrases leap out as portals into Dylan numbers:

Stories are simple. We all know them. Boy meets girl. Boy loses girl. Boy steals crust of bread. Boy gets gunned down in town square. Girl kills boy’s wife. Child grows up searching for father’s murderer. Girl marries boy. Boy burns down town.

Doesn’t that sound like the subtext to “Highway 61” or “Everything Is Broken”?

Think of this book as a lengthy footnote to the far preferable Theme-Time Radio Hour, where Dylan DJ’d an XM pay-radio network series (www.themetimeradio.com). Far from any philosophy or skill, this book captures the voice of a soul that seems to have shrunk in inverse proportion to his catalog’s reach and influence.

Boston