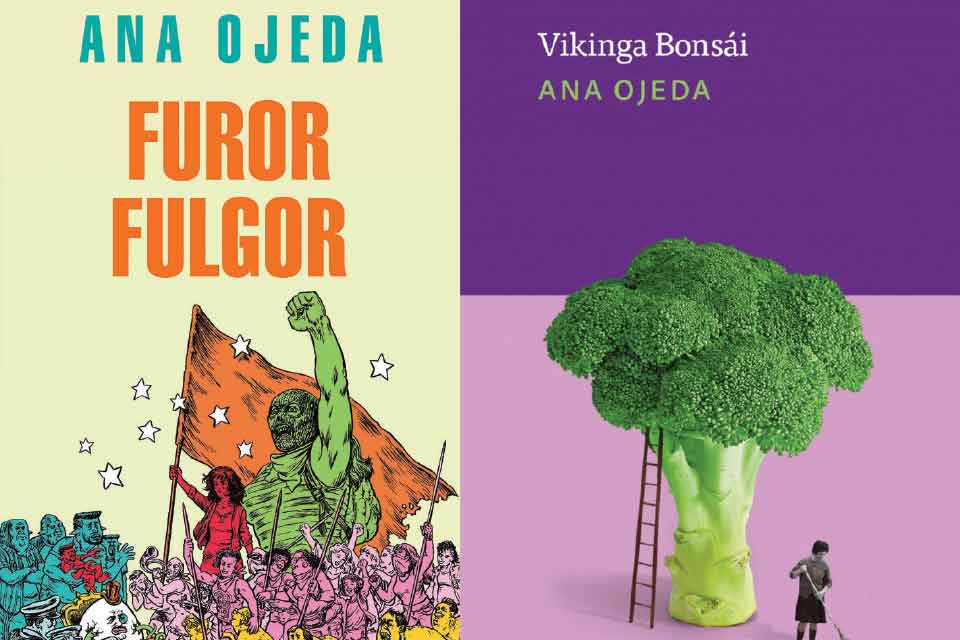

5 Questions for Ana Ojeda

Ana Ojeda’s new novel, Furor fulgor—set in a dystopian future where the government dictates that only one, hegemonic, form of language is legally acceptable—was already nearing publication when Buenos Aires banned gender-neutral language in schools. We checked in with this WLT contributor, who authored an essay, translated by Kit Maude, about using the letter e in the Spanish language to combat sexism.

Q

Did you anticipate bans on gender-neutral language in Buenos Aires?

A

Not really, but literature is often prophetic. Before Fulgor I wrote Vikinga Bonsái, in 2018. In it, I used gender-neutral language as a means into linguistic exploration but also to demonstrate that it was possible to write fiction with this morphing version of Spanish. As I was looking for the right publishing house for Vikinga (which turned out to be Eterna Cadencia, thanks to the enthusiastic generosity of their editor in chief, Leonora Djament), I began thinking about what it would be like if language were seen solely as a commodity (which is, in part, what’s happening today), which is to say that its circulation was set by law.

Literature is often prophetic.

Thus, for Fulgor, I created a government fed up with feminist demands and that, in a very gattopardesque way, gives away language to retain the means of production and the distribution of wealth as set in patriarchal society. Like the saying everything changes, so everything stays the same. As a symbolic repair of the violence and submission women had suffered throughout history, the government proceeds to rule that the legal obligation is to speak in feminine-“universal” language (in Spanish, instead of “UnO cree que . . .” or “TodOs piensan que saben . . . ,” “UnA cree que . . .” or “TodAs piensan que saben . . .”) for the population of Buenos Aires, as if feminine was indeed the universal for humankind. As though feminine were the default instead of masculine.

This upsets left- and right-wing feminist groups, and the civil war starts. In accordance with the decree, Fulgor is written in feminine-“universal” language.

Furor fulgor tells the story of Tootoo Baobab, a fed-up wife and mother of Pitón. One morning she decides she has had enough and abandons her home on the eve of the feminist revolution sparked by an attack on Google and the internet by a cyberfeminist international hacker group. This marks Year Zero of a new era. Tootoo is married to Ipiranga Trifulca, her revolutionary partner who, despite his Marxist education and understanding of the world’s capitalist oppressions, is unable to see the injustice of her having to do all the domestic chores and work side by side with him. Tootoo is indeed the servant of her lovely home until she decides that enough is enough and leaves.

I was keen to write about the left-wing blindness to women’s struggles in modern society: our exploitation as mothers and wives as well as workers.

I was keen to write about the left-wing blindness to women’s struggles in modern society: our exploitation as mothers and wives as well as workers, a blind spot that’s been there for almost two centuries. Many revolutionary men go back home to a clean house, a delicious meal, and three lovely, homework-completed, and bathed children. They think a lot about the emancipation of the proletariat without noticing that women are not part of the proletariat; we are another kind of worker: the invisible, unpaid kind.

Q

Is this ban part of a larger culture war across Latin America?

A

Throughout history, all across the world, people have struggled to emancipate themselves, both women and men. For me this ban was concocted in the hope of getting more votes from those who are against minorities getting more rights and ultimately against the redistribution of wealth. The feminist struggle is, first and foremost, a battle for equality, justice, and for a world without the exploitation of the vast majority by the few. It also stands for a society that sees the earth as a precious, complex organism, which we have to care for because we are part of it, and not just seeing it as a commodity or an opportunity to get obscenely rich at the expense of the lives of others.

Q

You live in Buenos Aires. Can you share a few favorite spots?

A

My favorite places in Buenos Aires are bookstores: El gato escaldado (@elgatoescaldadolibros on IG), the beautiful and very well-stocked bookshop of Boedo, the neighborhood in which I was born and still live and a historic breeding ground of left-wing literature: the neighborhood was home to many anarchist and socialist activists who worked to spread literacy among the working classes in the early nineteenth century; Eterna Cadencia (@eternacadencia), in Palermo, renowned for its exquisite taste in books and the incredible quantity of them on the shelves; and Céspedes Libros (@cespedeslibros), in Colegiales, a modern, witty, interesting bookstore, thanks to its owner, Cecilia Fanti, and her team of booksellers.

Q

What cultural offerings or trends have recently captured your attention?

A

In music, I follow with interest Argentine producer Bizarrap and trap music in general (WOS, Cazzu, L-Gante) because these singers/composers use rhyme in their lyrics and have a very playful linguistic spirit, which I appreciate. I’m currently writing in rhymed prose (or, as I say in Spanish, in “versosa,” verso+prosa), and I feel somewhat accompanied by them.

Q

Who are your favorite dystopian writers?

A

All writers are dystopian writers to some degree. I’m currently enjoying the literature of Argentine writer Marina Closs (Tres truenos, Monchi Mesa, Tascá Skromeda, La despoblación). She was born in Misiones, up north near Paraguay, and she uses Spanish in a very different way from what I’m used to, intertwined with Guaraní, Portuguese, German, and Dutch. She writes about rural life with characters that most of the time are isolated by nature or in small communities. Her writing enthralls me every time.

Ana Ojeda is a writer and editor. She has published numerous books in different genres for which she has won several awards and honors that particularly note her work with rioplatense language. Her novel Vikinga Bonsái (Bonsai Viking) has received widespread critical acclaim. Her Twitter and Instagram accounts are @anaojota.