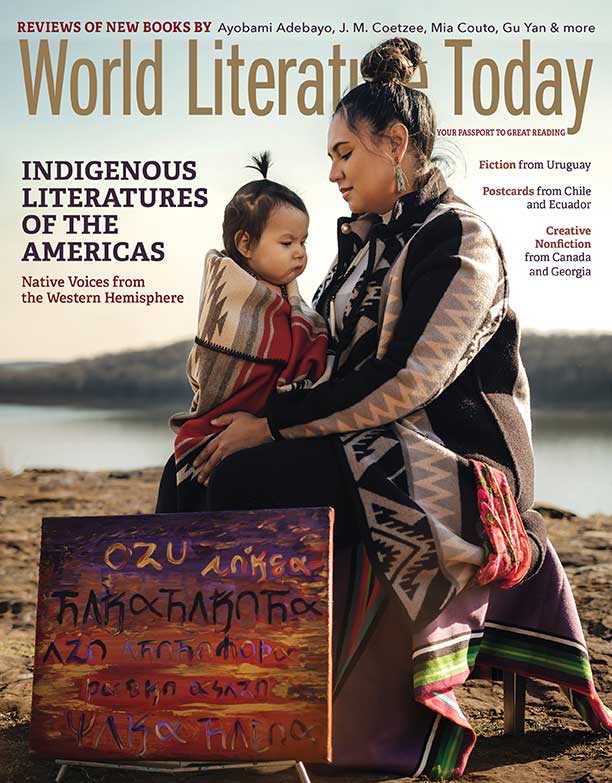

Making Things Brighter for the Next Generation: A Conversation with Oscar Hokeah

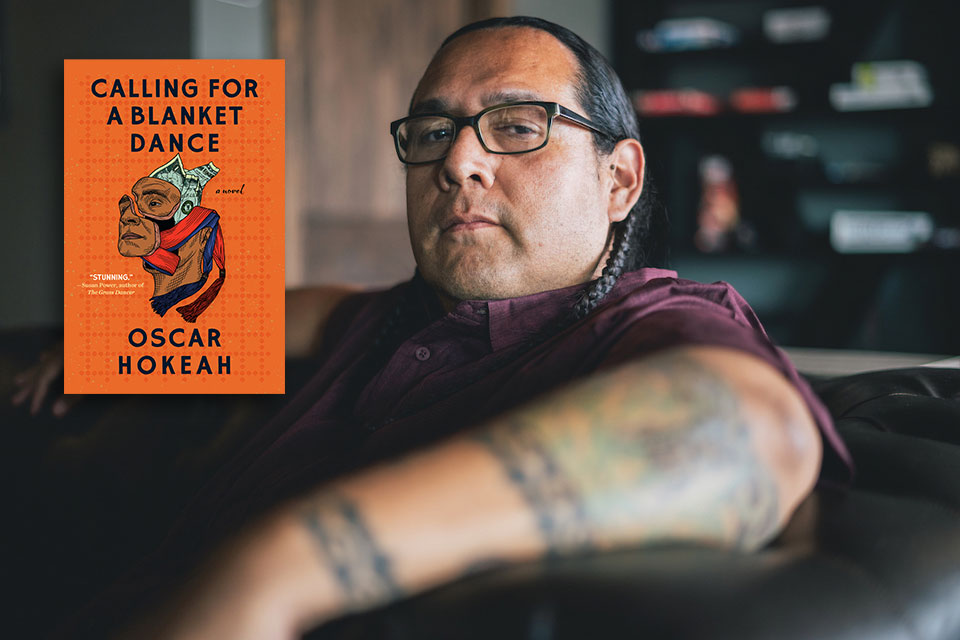

Oscar Hokeah’s Calling for a Blanket Dance, a cutting novel about challenge, resilience, and the support of one’s community, won the 2023 PEN America/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel and was named a finalist for two other awards. Hokeah, a Kiowa-Cherokee and Mexican writer living in Oklahoma, with twenty years of experience uplifting Indigenous communities, channeled his love for community into this debut novel. I sat down with him for an interview, discussing the transformation of personal experience into fiction, his passion for working with Native youth, and the importance of community and decolonization.

Oscar Hokeah’s Calling for a Blanket Dance, a cutting novel about challenge, resilience, and the support of one’s community, won the 2023 PEN America/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel and was named a finalist for two other awards. Hokeah, a Kiowa-Cherokee and Mexican writer living in Oklahoma, with twenty years of experience uplifting Indigenous communities, channeled his love for community into this debut novel. I sat down with him for an interview, discussing the transformation of personal experience into fiction, his passion for working with Native youth, and the importance of community and decolonization.

Kyrié Eleison Owen: I’d love to talk about your passion for fiction. Although you draw from personal experience, you choose autofiction over memoir—what is your guiding energy behind this choice?

Oscar Hokeah: When I was fourteen or so, I started reading fiction: Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Clive Barker. I fell in love with the genre early on, and I guess I wanted to write fiction based on my life, but, you know, I was so embedded in fiction that I didn’t think about it.

I did take a nonfiction class at the Institute of American Indian Arts. I think I was so entrenched in it because I write about some intense situations. I write about the abuse I got from my father, which shows up in the book. And just some of the trials and tribulations of negotiating relationships and losing a daughter; I lost a daughter the same way as my character Ever Geimausaddle.

Writing fiction and with peripheral narration gave me some distance. I do write for catharsis, and I am looking to find a way to emotionally heal. Even the second book is kind of loosely based on real situations I’ve encountered, but I’m gonna stick with fiction just because it’s easier to deal with indirectly. I guess you might call it shadow work and psychoanalysis, confronting some of those darker aspects that have happened.

Owen: Thinking about personal experiences informing your stories, would you say that you use the experiences of others’ lives, too, or do you take more freedom with other characters’ stories?

Hokeah: The reason I draw from my personal life, the lives of my friends and family, has to do with this emotional charge I need to have. Because if I have that energy, like a moment where I laugh with friends or family, then it transfers into the words for an emotional impact on the reader. Writing that broad spectrum of emotions, blending emotions, such as deep sadness and hope at the same time, is just as important as craft. Like Vincent Geimausaddle’s chapter: toward the end, we know that he’s passing, but there’s tremendous hope at the same time. It just makes the emotion that much more intense.

When I’m thinking about scenes, I’m always thinking of what emotional element to put into the storyline so the reader will be just as invested as I am.

It also makes more sense for me to look at these issues from the community’s perspective. I don’t know if that’s how I tend to do it in my personal life as I’m going about my day. I’m quiet because I’m always in my head. During conversations, I’m doing a cross-comparison with this other person and my characters or scenes. Stories are happening around us every day, and I’m going to find a way to connect them in my writing.

Blending emotions, such as deep sadness and hope at the same time, is just as important as craft.

Owen: Switching gears, you’ve called Calling for a Blanket Dance a “decolonization narrative,” which centers Indigenous resilience in the face of intergenerational trauma. This reclamation isn’t just the story but is within the book’s structure. Unlike Western storytelling, with a single narrator and linear structure, your novel takes on multiple narrators and multiple stories. How else do you decolonize storytelling?

Hokeah: When I think of decolonization, I immediately think of healing. I’ve worked with at-risk Native youth for the majority of my working career, almost twenty years, much like Ever working with Leander Chasenuh. Experiences that I share about Leander are from real experiences that youth have experienced. That’s one of the more important decolonization elements for me—adults who take on personal hardships, find a solid foundation, then transfer it to the next generation. This community has helped me, so now I need to pay it forward and need to help the next generation.

Then, broadening the lens, facing to the south. When we in the United States think of Native Americans, we think of United States Indigenous and Aboriginal peoples in Canada, but Mexico and Central America are filled with Indigenous communities. And the majority of the immigrants that are having the roughest time in Latin America are Indigenous people. So, we’re seeing a lot of relocation, not necessarily forced relocation, but economic relocation, transplanting and forming new communities of the same Indigenous groups here in the United States.

Challenging the dynamics of that border is also a part of decolonization.

To help shift more toward the south, it’s important where you have the main character moving back and forth across the border, that imaginary line made real by colonial powers. Ever was just trying to see his family. It’s not like if I needed to drive to see my sons in Albuquerque, New Mexico, from my home in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. It’s the same distance for me to drive from Tahlequah to Albuquerque as it is from Tahlequah to Adlama, Chihuahua, but for me to go to Chihuahua, I have to cross this border with all these obstacles that could potentially hinder me from seeing family. Challenging the dynamics of that border is also a part of decolonization, but it goes back to what you had mentioned with the structure of the novel itself being this modality for decolonization where we want to capture communal elements.

I hear people say, or try to say, Calling for a Blanket Dance is either a novel in stories or a collection of stories, but I think that does a disservice to the full narrative by calling it that because it’s a full experience based on a community. And, you know, Louise Erdrich had the same issue when Love Medicine came out. Everybody called it stories, but she did not put it into the world as stories, she put it into the world as a novel. It’s interesting that thirty years later, Natives are still dealing with the same stuff.

Owen: That communal nature is such a grounding force within the novel; I know readers will come away with that theme stuck with them. What else do you want readers to take away when they close the book?

Hokeah: Natives are diligently working toward healing and correcting historical trauma. I work with Indian Child Welfare with over a hundred people—over a hundred Cherokees all together doing different things to make the community better. Natives are doing work in the world to make things brighter for the next generation. That’s how we will survive these kinds of situations. And, you know, I hope readers walk away feeling that the community works together. This is why I titled the book Calling for a Blanket Dance; it reflects the blanket dance custom itself, like the entire community’s coming up to the blanket and offering a little piece of themselves for the betterment of Ever Geimausaddle. I hope readers ultimately walk away knowing that’s what we’re doing.

Owen: I have one more question for you. Looking toward the future in your next book, are you planning to revisit the lives of the Geimausaddle and Chavez families, or are you moving onto new characters and stories?

The second book takes a big chance, and it scares me in a good way.

Hokeah: I don’t plan on revisiting these characters. The next novel is a completely separate, completely different situation. The working title of the second book is Why Saynday Stole the Sun. It’s based on a traditional Kiowa story called “How Saynday Stole the Sun,” so there are elements that echo that traditional story. I don’t want to talk about it in too much detail and haven’t told anyone what it’s about. I was talking to the New York Times Book Review two weeks ago, and they wanted to know what was going on in that particular book, but I didn’t tell them either. I want to make sure that it’s all going to turn out the way I want and that my editor and I are on the same page before I start to talk about it.

But I will say it has much more teeth than Calling for a Blanket Dance. It’s much more intense, and it’s on a subject that Natives are not talking about, but probably the most important topic that we should be talking about. Because it has more teeth, there’s a part of me that’s scared of it, and I think that’s good. Even when I was writing Calling for a Blanket Dance, I was like, “Am I getting too real? Am I getting too raw?” I was a little bit scared of how close to that I was getting. But I want to do that—I want to write something that is going to potentially impact someone in a way where they can alter their thinking, and I can’t do that if I play it safe. So, for me to engage with something that I feel is going to be worth my energy and worth the reader’s energy, I need to take chances. The second book takes a big chance, and it scares me in a good way.

Owen: Calling for a Blanket Dance is already packed with brutal truth, so I’m gonna have to mentally prepare for your next book. As soon as you said it’s about something Natives aren’t talking about but need to, I’ve been tearing apart my brain trying to think of what it is.

Hokeah: When it starts to come together in time, I can start to divulge what it’s about.

Owen: I’ll keep an eye out for more interviews. In the meantime, thank you for taking the time to meet with me.

Hokeah: You’re welcome, and thank you for inviting me.

June 2023

Author’s note: We eagerly await Oscar Hokeah’s next book: the questions he’ll pry out, ways he’ll challenge the reader, and solace he’ll offer through his characters, bolstered by lived stories and personal experience. If Calling for a Blanket Dance is any indication, this upcoming novel will continue to cut to the soul, finding the balance between brutal truths and tender ruminations. Until then, let’s take a page from his book and uplift our community just like Ever and Hokeah.