Quito, Ecuador: A Literary Ode to Geraniums

See something once, and you see it everywhere. In Quito’s old town it was geraniums: on the curly-whirly balconies, in the porticoes of the old baroque buildings, and the great open squares, there were thousands of flower boxes coloring the city with red, pink, and white.

See something once, and you see it everywhere. In Quito’s old town it was geraniums: on the curly-whirly balconies, in the porticoes of the old baroque buildings, and the great open squares, there were thousands of flower boxes coloring the city with red, pink, and white.

Then, suddenly, I found geraniums everywhere: in the Irish gardens of Joyce’s Ulysses, and the Westmorland dales in Elizabeth Gaskell’s story “Half a Life-time Ago.” In Dostoevsky’s Poor Folk, when Makar Devushkin splurges on two pots of geraniums for his beloved Varvara Dobroselova, winning her over: “How much they must have cost you! Yet what a charm there is in them, with their flaming petals!” (A good sign for Makar, as Beverly Nichols wrote in Merry Hall that “anybody who does not love geraniums must obviously be a depraved and loathsome person.”)

Geraniums add a dash of color to Franz Hessel’s Berlin (“pulsing red in a sluggish gray world”), to Yevgeny Kropivnitsky’s Moscow (“red geraniums in pots / lining dingy windows”), and the pallor of Virginia Woolf’s England, where “the geraniums glow red in the earth.” They touched the poems of T. S. Eliot, Louis MacNeice, Amy Lowell, and Moroccan writer El Habib Louai, who wants to “read, read, / & look at geraniums until I fall asleep.”

Sylvia Plath’s heart was “a stopped geranium.” In The Rosy Crucifixion, Henry Miller kissed lips “soft as geraniums.” Geraniums were a favorite of Dickens, and he grew a garden of them at Gad’s Hill, his country home. Victorians like Dickens took their flowers seriously—they were their own language, each varietal and color symbolizing a coded message. The geranium embodied attributes as disparate as melancholy, ingenuity, friendship, and steadfast piety. Victorians believed geraniums cleaned the air of a sick room. They’re doing much the same in Quito, where they say, “Come back.”

In 1978 UNESCO thundered its stamp onto Quito’s head, citing the center’s “harmonious sui generis.” Such officialdom can be a curse. Rather than tackle the bureaucracy to repair the crumbling but protected buildings, residents simply migrated to more modern parts of the city. The grand houses were left empty, and the streets devoid of much life after 7 p.m. Walking the Plaza de San Francisco after dark, I had to look up for signs of life, to the yellow lights on the black mountainsides, like a swarm of fireflies rising to the heavens.

In the morning, in the din of the blue public buses, whose brakes honk like geese, I stopped to buy a punnet of strawberries from a young woman. Her long black braid gleamed under a dusty bowler. She called the center Quito’s “secret garden.” And like the secret garden of the Frances Hodgson Burnett novel, the Incas built Quito to be hidden from the outside world, safe in a bowl of green. Incan concern of invasion proved legitimate but unpreventable, and after the city became hispanicized, it grew outward, like a balloon squeezed in the middle.

Like the secret garden of the Frances Hodgson Burnett novel, the Incas built Quito to be hidden from the outside world.

Artisanry perseveres in Quito’s center, where felt hats, leather boots, and alpaca rugs are still handmade. Hand-carved wooden figurines of religious figures sell for a thousand dollars or more. No wonder: watching a sculptor dab blue irises on tiny glass eyeballs in his poky workshop was a lesson in mind-numbing exactitude. Each figurine is custom-made, and in Quiteño nativity scenes, called pesebres, you may find Jesus in his original cherubic baby form or in one of his many roles: cowboy, policeman, mariachi, posed as Rodin’s The Thinker, and so on.

The social program De Vuelta al Centro wants to save these artisans by bringing people back to Quito’s center, not just for the day, but as residents. The geraniums are theirs, too: by bringing beauty back to these streets, it’s hoped people will follow.

I didn’t dare pick the geraniums, but roses were different. My hotel put out bouquets of yellow and white and red, and, each morning, I filched one to stick in my lapel—one never knows whom one will meet. Or had met. I was reading Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn when, at page 200 (“What was there then in this book which could mean so much to me and yet remain obscure?”), a red rose petal, placed there by an amada, dropped into my palm: a message for me in this secret garden.

There are plenty of librerias scattered throughout Quito—Libreria La Luz and Huiñai Librería, while blue pop-up shops sell pirated books. The English Bookshop, on Avenida Venezuela, is the best bet for well-worn copies of English classics, and they boast an impressive collection in French, German, and Spanish.

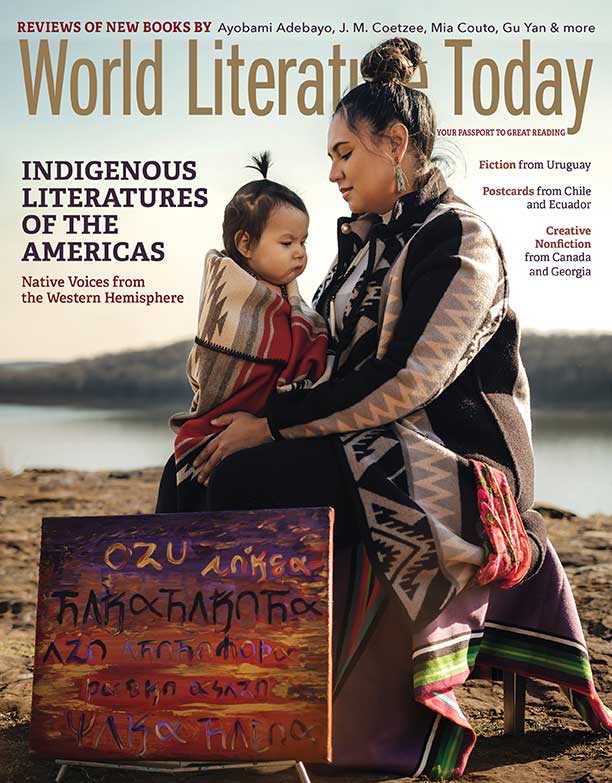

What to Read over a Piñol

Abdón Ubidia

Wolves’ Dream

Trans. Mary Ellen Fleweger.

Latin American Literary Review Press

Jorge Icaza

Huasipungo

Hassell Street Press

Javier Vásconez

El coleccionista de sombras

Pre-Textos

Luz Argentinaw Chiriboga

The Devil’s Nose

Trans. Ingrid Watson Miller & Margaret L. Morris.

Page Publishing

Gabriela Alemán

Family Album: Stories

Trans. Dick Cluster & Mary Ellen Fleweger

City Lights