Three Minutes on Music from Bangladesh

Go look up “Bangladesh” in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Hmm. There is an entry for “Bengali music,” but not one specifically for Bangladesh. Try the Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. There at least you will find an entry titled “Bangladesh and West Bengal (India).” Despite something of a classificatory discrepancy here—what other nation in the world is refused its own entry?—these scholarly choices seem reasonable. Why separate something that is inseparable? But West Bengal and East Bengal were indeed separated, first in 1905, then again in 1947.

No wonder that the doyen of Bengali music and literature, Rabindranath Tagore, is the composer both of the song that became the national anthem of India in 1950 (“Jana gana mana”) and the song that became the national anthem of Bangladesh in 1972 (“Amar shonar bangla”). Claimed as a native son by both motherlands, Tagore’s extensive compositional output remains very much in favor today, his songs being performed by all kinds of musicians working in all kinds of styles. Lesser known outside of South Asia is Kazi Nazrul Islam, thirty-eight years Tagore’s junior—deeply influenced by him yet with a distinctive poetic and musical voice, a Bengali Beethoven to Tagore’s Mozart. His songs are also performed widely today, and he is particularly revered in Bangladesh.

When Partition severed Bengal, Kolkata was of course its cultural hub, home to thriving music and film industries; Dhaka in the 1950s had nowhere near its technological infrastructure. The East Pakistan Film Development Corporation, founded in 1957, released films in both Bengali and Urdu through the 1960s; Swadhin Bangla Biplobi Betar Kendra, now the state-owned radio station Bangladesh Betar, played a prominent role in the War of National Liberation in 1971, broadcasting speeches and news along with patriotic songs. In recent years, Dhaka’s technological infrastructure has undergone a digital revolution. The increasing availability of inexpensive digital audio and video production software was transforming the music and film industries in the late 1990s, and widening Internet access in the 2000s has shifted patterns of consumption and distribution.

Along with technological transformations came new forays into both global and local musical styles. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed an explosion of rock and metal bands, including groups such as Miles, Warfaze, Feelings, LRB, and Aurthohin, groups that opened the way for later bands like Black, Artcell, and Némésis. In the 2000s the group Bangla, in particular, was experimenting with using traditional Bangladeshi tunes and instruments within a more modern cosmopolitan context. Predictably, such experiments achieved mixed results, with advocates praising their efforts to give old songs new life and critics wary of these dilutions or distortions of the purity of tradition.

The struggle over cultural identity that emerged in the aftermath of Partition continues today, with questions of westernization and globalization added into the mix. At heart, musicians see their work both as part of the venerable and complex history of Bengali music and as part of the more recent and complicated history of Bangladeshi music. Both of these histories resound with Western and global voices, from Rabindranath Tagore’s experiments in fusing Eastern and Western musical elements to Lokkhi Terra’s Nigerian-Cuban-British-Bangladeshi fusion.

Musicians wrestle with the same problems of cultural identity that concern writers, politicians, and rickshaw drivers. So what makes the expression of these issues in musical terms particularly powerful? Why music, not words, or art, or something else? In Bangladesh, music is the art form that reaches people from all walks of life. It stretches out to touch people living in rural areas, people living in cities, and people living abroad. It immerses people in shared anger, sadness, indignation, happiness, joy. And it unites people, whatever divides them: listen, for instance, to “Tin minit” (“Three minutes”), a song written by West Bengali singer-songwriter-politician Kabir Suman in February 2013 in support of the Shahbag Protest.

Suggested Viewing and Listening

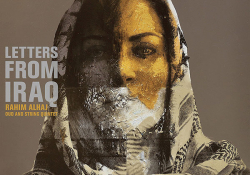

AUDIO: Srabonti Narmeen Ali, “Ghumiye thakai bhalo” (2007)

AUDIO: Arnob, “Lukiye” from Doob (2008)

AUDIO: Khiyo, “Amar Shonar Bangla” (2012)

AUDIO: Némésis, “Kobe” (2011)

Author note: This article is based extensively but not exclusively on a long and lovely conversation over e-mail with Srabonti Narmeen Ali, a singer-songwriter and freelance writer from Dhaka. My gratitude to her for taking the time to tell me about lots of things, answer my questions, and read my work. Thanks also to Sadia Rahman Rodriguez, a former student of mine, who put me in touch with her.