Delhi: 21st Century City

The twenty-first century has seen Delhi go from being just another nondescript capital city to a throbbing metropolis that mirrors much of the century’s ethos.

As a kid growing up in the 1980s, I couldn’t wait to leave Delhi. As far as I was concerned, it was far too insignificant to matter in the world. Forget the world. It didn’t even feature in the part of India that stirred the imagination. That distinction belonged to Bombay. Bollywood glamour cast Bombay as the city of dreams. Dalal Street, also known as India’s Wall Street, made it the nation’s commercial hub. The presence of Bombay-centric communities, such as Baghdadi Jews and Parsis with roots in Zoroastrian Iran, in addition to people from all over India, lent it a rich tapestry of culture. It straddled the nerve center of Indian imagination, achieving global fame as the city that brought Indian writing in English to the world in the eighties and nineties. Salman Rushdie’s Booker Prize–winning novel Midnight’s Children is set there, as are the novels and short stories of Rohinton Mistry. Calcutta came next in the pecking order. It was the capital of British India for much of India’s colonial experience, with Delhi only taking over that mantle in 1931. It was also the city of high culture, home to the writings of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore and the neorealist movies of the iconic Bengali director Satyajit Ray. Down south, Madras reigned supreme with a legion of academies devoted to the study and practice of classical Indian dance and music. Toward the end of the century, Bangalore shot to prominence as the Silicon Valley of Asia

Delhi languished in ignominy, a city known for little other than political intrigue and a brash, in-your-face Punjabi culture. Moreover, in 1984 it slid into the worst kind of infamy when anti-Sikh riots broke out in the wake of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination by two Sikh bodyguards. For four days Sikh homes and businesses were targeted by armed mobs, while the army and police stood about and did nothing. It was as if the city had rewound itself back to 1947, when it was rocked by Hindu-Muslim riots at the time of India’s independence from Britain. More than two thousand Sikh men, women, and children were butchered in Delhi in the four days of rioting. More than a century before those riots, the city’s preeminent Urdu poet, Mirza Ghalib, had written: “Lest we forget: It is easy to be human, very hard to be humane.” The riots were living proof of how relevant Ghalib’s words were in Delhi toward the end of the twentieth century.

I left Delhi three years after those riots. I was ostensibly going to America for college; in reality, I was escaping Delhi. I should have boarded the plane for America bursting with excitement at the prospect of moving to the center of the world. Instead, I merely felt relieved to be leaving Delhi. No way did I wish to spend my life in a place I had come to see as impotent and barbaric. Over the next two decades, I returned to visit but not to live. I only moved back to Delhi toward the end of 2011 and found a city transformed beyond belief.

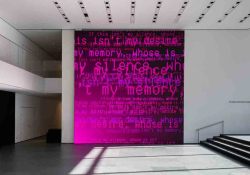

The Delhi I left in the eighties could have been accused of several things. Intellectual fervor, however, was not one of them. It was a classic capital city whose notoriety hinged squarely on being the capital of a country, kind of like Brasília or Canberra. The Delhi to which I have returned is nothing like that. It is an irrepressible cultural center that hosts international art exhibitions and festivals of literature, music, film, and dance. Furthermore, the culture it showcases has multiplied in geometric progressions since the eighties. I remember how taken aback I was to discover a Tamil film playing to packed houses in my neighborhood multiplex in 2012. In the eighties, it would have been unimaginable for a film that wasn’t in English, Hindi, or Punjabi to find an audience in Delhi.

Moreover, Delhi is now a place where art of every kind is not merely consumed; it is also created. In its outskirts, the city houses a Film City where movies and television programs are produced. It is home to numerous artists and musicians as well as writers, editors, and publishers working in several languages. On a typical day, I can meet my Malayali editor to discuss a book I am writing in English, talk to the Tamil editor of an English newspaper to which I have been a frequent contributor, and then go home to catch up with friends who write originally in Bengali and Malayalam and translate works from those languages into English—and not feel the least bit weird about it all.

The diversity found in the art produced in Delhi has coincided with its emergence as a truly diverse city. Even at the time of independence, Delhi was a city of migrants. India’s freedom from Britain was accompanied by communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims as British India split into India and Pakistan. Waves of Hindu and Sikh refugees poured into Delhi from the state of Punjab, whose western half went to Pakistan. Since then, the city has swallowed migrants from everywhere. The rate at which it has ingested people in the twenty-first century is phenomenal. In 1951 Delhi’s population was 1.74 million. In 2001 it was 9.8 million. Today it is close to 20 million!

Delhi is the one city I know of where street names are inscribed in four languages—Hindi, English, Urdu, and Punjabi—and yet do not even begin to capture the city’s ethnic and racial diversity.

Given Delhi’s circular shape, it wouldn’t be wrong to compare its growth to that of a belly ballooning to the size of a sumo wrestler over six and a half decades. But it is not the size of the bloat that distinguishes a city. What is remarkable in Delhi’s case is that the constant influx of migrants has guaranteed that the city lacks an ethnic core, which has made it something of an anomaly in an India only too happy to flaunt its ethnic stripes. Since the nineties, Bombay has become Mumbai, Calcutta has become Kolkata, Madras has become Chennai, and Bangalore has become Bengaluru. The name Mumbai instantly labels the city Marathi; the name Kolkata dubs it Bengali; the name Chennai brands it Tamil; the name Bengaluru stamps it Kannada. Delhi, on the other hand, belongs to no one. It is the one city I know of where street names are inscribed in four languages—Hindi, English, Urdu, and Punjabi—and yet do not even begin to capture the city’s ethnic and racial diversity. In the eighties, Delhi was merely a North Indian city with a large Punjabi refugee population. Today it is home to Indians from all over India, including thousands of migrants from India’s northeastern states who are East Asian in appearance. It also houses a fast-growing population of expats. As recently as the nineties, a foreign face in Delhi invariably belonged to a diplomat. Today people from all over the world live and work in Delhi. In the eighties, foreigners could be found in a handful of posh neighborhoods. Today they are scattered all over, and they come from everywhere instead of a few Western nations with interests in India. For instance, in the eighties an African face was rare. Today the city has its own Little Africa in the neighborhood of Khirki Extension.

If the twentieth century was about gaining freedom from empire, irrespective of whether the empire was British, French, or Russian, the twenty-first century has shown a penchant for delivering humanity from another kind of imprisonment—that of ethnicity. It is a century where a global pop star singing in English can have a name like Zayn Malik and Pakistani ancestry; where an Italian boy band called II Volo can became a worldwide sensation singing “O Sole Mio”; where a Bollywood actress called Priyanka Chopra can play an FBI agent with aplomb on American network television; where an assembly line of Scandinavian novelists writing originally in languages spoken by less than ten million people can dominate a genre as commercial as crime fiction; where America can have a black president . . . Crossover is the mantra of the day, and breathing simultaneously in different cultural milieus is commonplace.

With no traditional center and a constantly shifting population, Delhi slides far more seamlessly into the ethos of this most global of centuries than any other major Indian city—so seamlessly, in fact, that it reflects much more than the century’s promise; it manifests many of its challenges as well. If the new century is at its best in its embrace of diversity, it has also served notice of the fact that intolerance is not yet ready to give up its castle. That is amply reflected in Delhi. In the twentieth century, Delhi’s chauvinism was religious. Three decades after the Hindu-Muslim riots at the time of independence, anti-Sikh riots lent wings to an incipient Sikh militancy that terrorized the city until the mid-nineties. Since Sikh bombs have stopped going off, Hindu-Sikh relations have recovered their amity. Memories of what happened in 1947, however, continue to dog the Hindu-Muslim relationship. The actions of jihadist outfits and right-wing Hindu organizations keep renewing the suspicion and animosity. Moreover, over the past ten years, racism has taken root with the city’s most recent arrivals, Africans and Indians who are East Asian in appearance, bearing the brunt of hate attacks.

If the twentieth century was about gaining freedom from empire, the twenty-first century has shown a penchant for delivering humanity from another kind of imprisonment—that of ethnicity.

Coupled with extreme prejudice is the trepidation surrounding Delhi’s air. The twenty-first century’s warning about the environment sounds in Delhi with the urgency of a red alert. Nowhere is the air quality poorer. Road dust, vehicular emissions, and carbon dioxide discharges from power plants conspire to produce a haze that rivals the one that hovered over Mexico City in the nineties. Furthermore, the city remains in constant conflict with itself as it seeks to replace age-old patriarchy with the new ideal of gender equality. Rather than adapt to a generation of working women, who are very different from their stay-at-home moms, a section of Delhi’s male population responds to the changed reality by exhibiting the kind of ferocity that ensures Delhi figures prominently on the roster of cities notorious for crimes against women. December 2012 saw the city plummet to its nadir in global infamy when a twenty-three-year-old woman became the victim of a fatal gang rape in a moving bus.

The Delhi I left in the eighties would have retreated in the face of such challenges—kind of like it did during the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, where most Delhiites were content to sit at home and do nothing while innocent people were being killed. And how could they do otherwise? They saw themselves as Hindus, Muslims, or Sikhs; as Bengalis, Tamils, or Biharis . . . as anything but Delhiites. Today’s Delhi has a far greater sense of its own identity. I remember a conversation I had with the writer Nilanjana S. Roy toward the middle of 2012. We were talking about her novel The Wildings, which had just come out. I was taken aback when she dubbed it a love letter to her city, Delhi. Roy is a Bengali who grew up in Calcutta and only came to live in Delhi when she started college. Yet she considered Delhi her city. Something like that would have been unimaginable in the eighties.

This enhanced sense of identity gives me hope for Delhi’s ability to face up to its challenges. To an extent it has already started doing that. While tension between different communities continues to fester, there hasn’t been a major communal riot since 1984, even though the city has been hit by terrorists on several occasions. Condemnation is swift in the wake of hate crimes and crimes against women. Half the city took to the streets in a show of solidarity with the twenty-three-year-old who was raped and killed in December 2012. And even as I write this essay, Delhi has finally quit bellyaching about air pollution and stirred itself to do something about it by placing curbs on the number of private cars plying the streets.

A new century represents much more than the march of time. It represents the march of history by ushering in new eras and consigning others to the past. New cities rise to prominence, while those that were once prominent retreat to the shadows. Delhi’s rise is very much a twenty-first century phenomenon. That, perhaps, is the reason why it catches so much of the new century’s ethos.

Over 150 years ago, Mirza Ghalib wrote: “I asked my soul: What is Delhi? She replied: The world is the body and Delhi its life.” These days I find myself mulling over those words in the way you mull over an epiphany. When I came back to Delhi toward the end of 2011, I did not return to live. I thought I was merely pausing to catch my breath before pressing on to some place more fulfilling. More than four years later, I am still in Delhi, and the cities I lived in while I was away appear to be places I was passing through on my way home.

Delhi