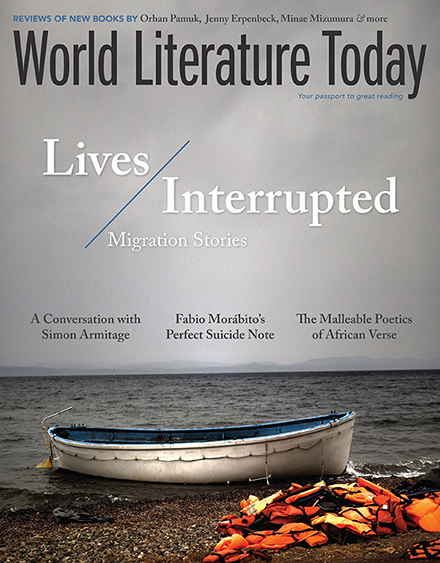

A Good Prisoner’s Handbook

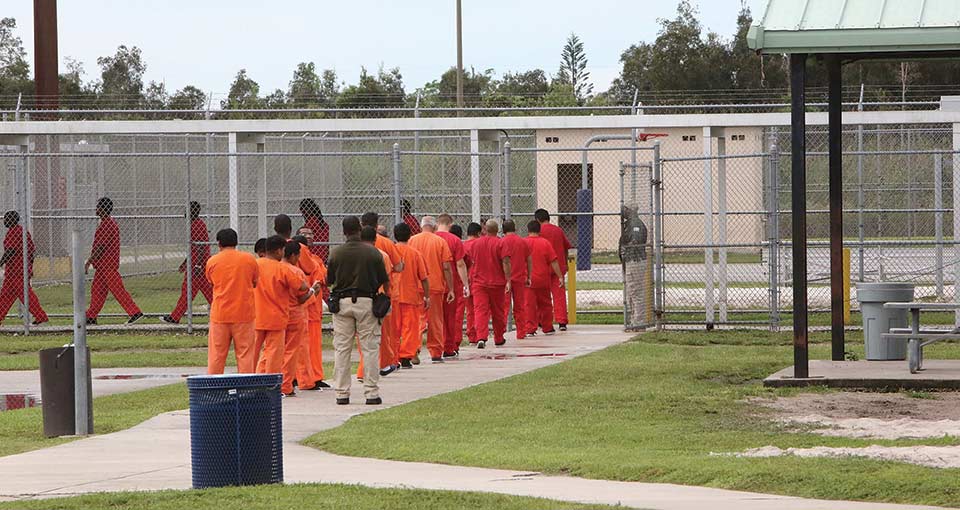

Photo: Miami Herald / Getty

Photo: Miami Herald / GettyFor some years, Enrique Ferrari, known in Buenos Aires as Kike (kee-Kay), lived in the United States. His stay ended the day a traffic cop asked him for his papers and he didn’t have anything to show him. He was undocumented. He spent the following seven days in the Krome Detention Center, the same place where the story of Scarface begins. This is his account.

1.

My uniform is blue. That means I committed no crime. Or, rather, that they didn’t catch me committing any crime. If I had had a forged social security card, for example, it would be falsification of a public document, and I could have served up to seven months in a federal prison. Then my uniform would be orange.

If I had punched the police officer at the moment of my detainment, my uniform would be red: violent crimes. The detainees in one color of uniform never mix with those of another color. For all:

“the clothing to be used will be limited to one shirt, one pair of pants, one pair of shorts, one undershirt (only in winter), one pair of sneakers, and one pair of slippers.”

I know this because the Good Prisoner’s Handbook says it.

2.

They give you the handbook with your clothes, your bedding, your personal hygiene—right after you hand over your clothes and belongings, and before the doctor examines you after arriving at the Krome Detention Center—the place where the young Tony Montana is being held at the beginning of Scarface.

“The purpose of this handbook is to explain to the detainee rules, regulations, guidelines, and specific procedures that must be followed while in the custody of this center.”

It is a tiny notebook with a faded sky-blue cover and, on its center, the shield of the Department of Justice, Immigration & Naturalization Service and, above that, “Translation from English to Spanish.” The only words in English. There is also a phrase written in Latin: Qui Pro Domina Justitia Sequitur. Our Lady that pursues justice.

3.

Apart from the handbook and the uniform, you get a plastic bracelet for your right wrist with a very long number and your country of origin. I, for example, while I am here, will be called either Argentina or by the last three digits of my number, -911. While I wait for the doctor to see me and to receive the results from my X-ray, I flip through the handbook looking for any clues that will offer a glimpse into my immediate future. They are quite interested in assuring that I don’t have tuberculosis.

Page 15, Series 100 violations (first degree), code 101. I read: “assault to any person (sexual assault included).” Page 18, Series 200 violations (second degree), code 205 “committing sexual assaults.” 206: “making sexual propositions or threats.” Sanctions: “(a) beginning of criminal processing, (b) disciplinary transfer (recommendation), (c) disciplinary segregation (up to 15 days), (d) compensation.”

I think of Midnight Express, of The Tombs. I feel my legs weaken. I imagine a pointless fight against three or four detainees, broken teeth, and the inevitable ending. One week later, when I go home, the only thing I will take from Krome will be a bad cold. The gringos turned the air-conditioning up too high.

4.

But before I arrived at the Krome Detention Center and before the Good Prisoner’s Handbook fell into my hands, there was an intermediate step: Border Patrol. Some sort of cave nearby the University of Fort Lauderdale.

I go in and they take off my handcuffs to search me for the third time.

An overweight man in a brown uniform signals me to sit in front of a desk. He settles in on the other side. He asks me questions and fills out a form. I don’t pay him much attention. Behind him a sign warns me:

← Cubans | Others must be deported →

They search me one last time and send me to the cell block. The cell block is large. I am alone. In a corner, with a meter and a half of privacy, there is a very dirty toilet. Two cement benches are built into the wall. There is a blanket. The rest of the cell is bare walls with bloodstains and various graffiti:

The Macho of Sinaloa

Medellín is in charge

They breastfed Chucky.

Things like that.

Don’t let them bring anyone else, don’t let them bring anyone else, don’t let them bring anyone else.

A moment later—an endless moment—the overweight brown uniform returns. He searches me again and asks me if I have any bladed weapon.

Of course, after searching me five times, they ask if I have a bladed weapon.

Where you’re going now, they’re not going to like it if they find something, he warns me.

Where am I going now? I wonder.

They already caught me, they have me here in this foul cell, now send me home.

I saw the sign when I arrived:

Others must be deported →

I am one of the others! I want to go to Buenos Aires. But no, Krome awaits.

5.

In the cell block where they take me about 150 men sleep in beds, cots, and bunk beds. They wait for their permission for asylum or their moment of deportation. They cluster together in groups by nationality. There are Eastern Europeans, a lot of Haitians, Mexicans, Colombians, and some Israelis. I will find out the following morning that I am the only Argentine.

“Since you will live in a dormitory with other individuals, your personal hygiene is essential. We ask that you bathe regularly and keep your hair clean.”

If, like the cross-eyed Jean-Paul believed, Hell is the other’s gaze, Krome must arrive with Charon’s boat. The showers don’t have dividers or curtains. Nor do the toilets. They are in a big semicircular room. You have to shit and wipe your ass looking the other detainees in the face. I lasted the first three days without going to the bathroom. You don’t want to know what the fourth day was like when I threw in the towel.

6.

“Breakfast is at 6:30 a.m., Lunch at 11:00 a.m., Dinner at 4:30 p.m. Room lights will be turned on at 5:30 a.m. each morning to provide the detainees an opportunity to clean themselves for breakfast.”

The food is horrible but abundant. The first breakfast I sit at a table with Colombians and Mexicans. Like I already said, I am the only Argentine.

You guys leave immediately, one of the Colombians tells me. I smile.

Twenty days, one month at the most, he adds. Now my smile falters.

In the meantime, you’re with us, he says. Now he smiles.

7.

“Access is permitted without restriction to all reading material, except for legal publications.” I read.

I read like a possessed man. Between the piles of Bibles and trash I find a book about Chile de Debray, another about the origins of the Franco regime, Gauguin’s correspondence from the South Seas, and some detective novels.

8.

“In order to maintain proper control of the number of detainees in this center, there will be an official count various times throughout the day.”

After the last count one night, everything got strange. You could hear sounds; running about and guards coming and going. They counted us again and again. Finally, one of the guards, Tom, explains to me, half a dozen Haitians, the ones told they were not going to receive asylum, escaped. No one knows how, but they breached the perimeter.

And will they go out and search for them? I ask.

Outside there? Tom lets out a hearty laugh. No, at Krome we don’t chase anyone once they cross the fence. This is a swamp. It would be too dangerous.

So? I reiterate my question.

By this time of night, the crocodiles have probably eaten them, he responds playfully.

9.

Six days later, while I play cards with one of the Colombians, he makes me an offer. It sounds like an offer I won’t be able to resist. He proposes that during one of the breaks that we have (“all of the detainees are able, if the physical and meteorological conditions permit it, to have a minimum of one hour of recreation outside”) that I give a package to a fellow countryman of his who is in a different cell block.

They are always watching us so closely, he explains, and all nod in agreement, whereas you guys, they don’t even look at you.

I return his smile and don’t say either yes or no.

We’re friends, right? he suggests. We don’t cease playing, but now no one pays any attention to the cards.

Series 200 violations (second degree), code 216: “The giving or receiving of money from any person with intent of smuggling contraband or any other illegal intent.”

We will give you one hundred dollars for the favor, the Colombian adds. They all watch me. They wait for an answer.

“This center allows detainees to have funds that do not exceed forty dollars.”

I don’t remember how I maneuvered my way around them—I think I told them something like, “We’ll see tomorrow!”

I was saved by the bell. There won’t be a tomorrow. Tonight, at close to five, I will hear the yell: “Argentina, -911! Gather your things!”

10.

I am on the plane on my return home. They escorted me in handcuffs to the airport and boarded me onto the plane before the other passengers. They are not going to return my passport to me until we get to Buenos Aires. I’m sent off with only the clothes on my back: a red sleeveless T-shirt, socks, a pair of shoes, and jeans. In one of the jean pockets my wallet with my US driver’s license, a bank card, and twenty dollars. In another, a tiny journal with a faded sky-blue cover. I open it and read:

“This guide must be returned in the condition in which it was issued, consequently, do not write in it, mark it, or subject it to any abusive treatment.”

I think, I’m going to have to write about this someday.

Translation from the Spanish

By Paul Holzman

Editorial Note: Read an interview with Kike from this same issue.