Zeroes

The binaries of life bite at 3 a.m.

You don’t need to fast-forward time.

Envision vanishing before it happens.

For those who care to look, profiles remain.

They stumble upon them in the sunlight.

In this short essay, Slovene author Leonora Flis is both reduced to and saved by numbers while living as a foreigner in New York City.

She remembered standing in line waiting to be assigned a number, to be measured, weighed. She felt so uncomfortable and so self-aware that her body shook intermittently. She began to shift from one foot to another even more restlessly. Her mind raced with uncomfortable thoughts. They pounded on the left side of her head and then crashed with all their force to the right. Probably a slight case of obsessive-compulsive disorder. These thoughts that she never let rest. Do you have the things they want, did you leave behind the things they don’t? Will the numbers be all right? It was awkward but also a little bit entertaining. The thought that she doesn’t weigh enough.

When she gets close to the scale, sharp talons of fear scratch at her brain telling her she is too invisible. She scopes out the competition. I cannot be that tiny; my long hair should add an ounce or two, she consoles herself. She lifts her head and glances without blinking at the boys and girls around her. “Well, come on, dear, get up on the scale,” a woman’s voice says. “My goodness, you’re light as a feather. I’ll let you through, but in first grade you’ve got to gain some weight, okay? Do they feed you enough at home?” she adds, half-patronizing, half-joking. The curly, blonde-haired girl is so overwhelmed with joy she does not answer. She’s going into first grade! The numbers are just right; she had made it through the system that gobbles up numeric sequences and spits out charts. For a moment she thinks about the number she was assigned at birth. Her mother had shown her the white bracelet from the hospital. It had her name, weight, length, and ID number. All of which is replaced with a new number early that afternoon.

Above all, it felt foreign. Once again. More so because she was a foreigner. Legal alien, they told her.

Now she had so many numbers that she sometimes messed up when she had to jot down a particular sequence. “The line starts right there, right in the back,” an official in a gray suit told her, pointing at the long line of people that snaked around the fifth floor of that 1930s Social Security Administration building on 237 West 48th Street. Some sort of vital records office. Of which there are at least twenty in each part of the city. She had been assigned to Midtown. Again her thoughts march to and fro. “I have all the documents I need with me,” the girl whispered to herself, moving her lips slightly. She is still slender, though her hair is no longer wheat-blond but a deep mahogany. It ripples down her back as it always has. Smooth, without clips or elastics to guide it. The girl declared that freedom was the dearest, most precious thing in her life—even when it came to hair. But red tape and freedom do not really go together, and whenever she was in an official agency, the whole affair of being assigned different labels and numbers left her both slightly amused and a little bit afraid. Above all, it felt foreign. Once again. More so because she was a foreigner. Legal alien, they told her. A legal Martian, an extraterrestrial with an official seal.

There were only a few drops of water left in her bottle and the line was moving very slowly. The air-conditioned room had some tables and chairs, and the rest of it was filled with small windows and robotic officials wearing absentminded stares, moving their hands, heads, and lips almost motionlessly. Her legs and toes were so cold she began to shift from one foot to another. I should have learned by now, she thought, to wear closed-toe shoes if I think I’ll end up waiting more than two hours in an enclosed space in the middle of an American summer. Finally she moved to the beginning of the line, and a beautiful black woman motioned her over to her counter. “It’s going to take between six to twelve weeks to verify and process the information, ma’am,” she said in a mechanical voice, winking her turquoise eyes, which were adorned with eyelashes so thick her eyes could scarcely close all the way. The woman had certainly repeated that sentence at least fifty times that day. “We need to verify that your information matches our records. The National Security Agency forwards it to us.”

They start a file on you as soon as you cross the border. It used to be on Ellis Island, now it was in the airport terminals where German shepherds sniff your checked baggage and bark at even the slightest trace of a sandwich. The social security number is an important matter. You get it once in your life and it’s yours till the end. Then they probably pass it on to someone else. Recycle it. But it has nothing to do with any kind of social security. She wanted to know who or what exactly this SSN—as it was usually written on forms—served. One explanation, the most reasonable one she had found, made it clear it was something similar to a tax number, something she understood from agencies back home. Just a tracking number. For documenting individuals. So they can settle their obligations and duties.

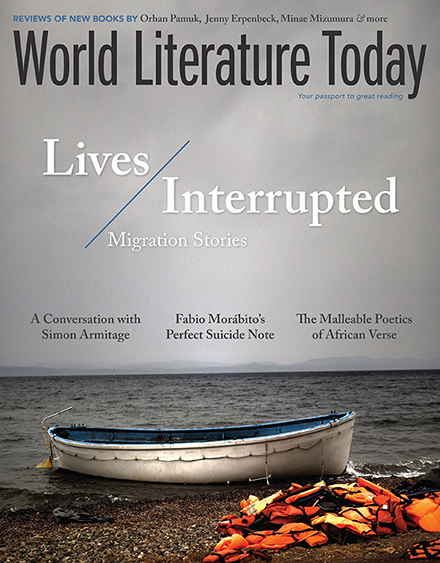

Invisible “zeroes.” With wages that were barely sufficient for life on the margins, with a three-hour commute to work every day, with expressionless, exhausted stares in jam-packed subway cars, yet with unwavering faith in the American dream.

And then there were also illegals, who were either deported or enslaved into doing the sort of work that locals wouldn’t touch. America was, of course, no exception in this regard, she often thought. Undocumented migrants were there to dig ditches in even the most unbearable heat, to repair drains, to clean toilets, and in slightly better cases, to rush around town on bicycles during peak hours to deliver food in bags emblazoned with “We love our customers” or, in the best-case scenarios, to walk dogs or to nanny for the children of wealthy families in Upper Manhattan or the better-off parts of Brooklyn. Invisible “zeroes.” With wages that were barely sufficient for life on the margins, with a three-hour commute to work every day, with expressionless, exhausted stares in jam-packed subway cars, yet with unwavering faith in the American dream. For which they were willing to sacrifice anything. Including their own lives.

In a few days, a drama much less significant than the sort that burdens immigrants from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Africa, and South American countries will unfold on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. A Martian with a legal status that already includes an SSN will lose her ATM card and the entire stipend in her account. American account, American rules. This will all happen on an early fall night, the first time she has decided to unwind, a moment when she will finally be able to take a longer break from intensively cleaning the apartment (the previous tenant must have been very busy or just plain dirty) and from the overabundance of administrative errands that come with temporarily relocating to a new place. A well-deserved drink at the bar on 3rd Avenue on the side where the East River flows will be too much of a treat that evening.

In a moment of distraction, her ATM card will go missing, the one from Chase, which probably has the most ATMs in Manhattan. She won’t notice it when she enters the building at 537 East 81st Street. Not even when she reaches the top of the stairs and the door of 5C. Numbers. They signal happiness, her home, her walls, her windows. After a few hours of sleep she will wake up with a hangover and instinctively reach for her wallet. She will sober up immediately. Her first thought will be to cancel the card. Again, numbers. This time, on an automated answering service that might lead to a live voice after half an hour, if you get lucky. She has never liked automated answering services, but America forces them on you at every step. The answering service will go back and forth and in the end require a social security number. God bless the SSN. The blessed numbers could save her from becoming destitute. She will press the numbers and wait. She will press them again. Nothing. It won’t work. The recorded female voice will sound polite yet totally unclear.

In that moment, she will remember that in the midst of some conversation she once overheard that zeroes usually work. Pure, simple zeroes may be the quickest way to reach a live person. She will press zero. Five times. That’s what she’ll remember. She will wait, and then suddenly hear a friendly female voice on the line. Bingo, now we’re talking, her brain will tremble. The account will still be intact and have enough to cover a modest amount of food and her outrageous rent for a few months. She will have mastered the art of pressing zeros on the phone, and from then on she will be able to resolve major and minor snags with zeros.

In her free time, she wants to learn about the lives of the invisible, unrecorded people at whom the system flashed a red light or quickly scanned and then looked beyond with an empty, disdainful glance so that they could be filed away in a drawer full of “zeroes.” In midwinter she becomes a volunteer in the streets of Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn. She is in the company of homeless people almost every day. Impoverished natives, unemployed legals and illegals. She distributes food, clothes, and words but never numbers. She counts only new acquaintances. Every story had a face, a first and last name, a mother or son, brother or sister, losses and days of triumph. Spring comes along with the stories. Japanese cherry trees start to bloom in the park, and soon after come the lilacs: white, purple, and pink.

Translation from the Slovenian

By Kristina Zdravič Reardon

Editorial note: From Upogib Časa (LUD Literatura, 2015).