Made Flesh

A Lutheran seminary student wonders what it takes to become a Jew for his girlfriend, whose embrace is “not a preface to anything else.”

I met my wife, Maria Madeleine,” the pastor began, “on the last day of classes during my second year at Uppsala University. The two of us were in a course entitled ‘Flowers and Nature in the Work of August Strindberg.’” He said “Strindbari” the way it’s pronounced in Swedish. “The course was an elective open to students from various departments. My wife, who was an avid student of mathematics, came to the lectures in order to clear her head a bit, as she put it.” He paused for a moment and then sang, “Maria, Maria, Maria,” like the song from West Side Story. “She was Jewish like only a Maria Madeleine could be: slight, her hair a dark thicket, her cheeks sunken, her black eyes burning, raven-like. From the very beginning she sat in the front row of the classroom and engaged the professor in an impassioned debate about the haystacks in Fröken Julie and the hollyhocks in Ett drömspel with a fervor and fury that confounded me. ‘Maria Madeleine,’ he said at the end of the third class, when it seemed he couldn’t bear her any longer, ‘If you would, come to my office hours. There’s something I’d like to say to you.’ Much later, she told me that their meeting began with his attempt to persuade her to free up some room for others. Or, as she told me, her laughter tumbling forth while she ran ahead of me barefoot through the hay and the tall, greener-than-green grass, ‘He just wanted me to let someone else get a word in edgewise.’ But she persuaded him, too, that only he and she and she and he, the two of them together, could speak about nature in Strindberg’s plays and pursue its beauty, like a pair of bright butterflies drunk on heat and short on time.

“I, who approached the podium just once from my seat at the back of the lecture hall, attempted—and I’ve admitted this already—to escape her burning gaze. But it was in my attempt to evade her and on account of her frenzied movements that I bumped into her. ‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ I said. But she smiled with a pleasantness I didn’t expect and responded, ‘No, no, don’t be sorry—it’s fine.’ And she walked off. I gathered my belongings and followed her down to the mostly forsaken expanse of lawn between the university buildings. ‘It’s only in photos of Berkeley,’ Maria Madeleine told me, ‘that there are students sitting on the grass. Here it’s still too cold and wet at this time of year. And by the way, what department are you in?’ I told her that I was a theology student, that I struggled with Semitic languages, Hebrew most of all, and that I hoped to complete my studies within a year and find a position in one of the churches, if not here in Uppsala, then maybe in one of the suburbs of Stockholm, or perhaps in Dalarna, or even somewhere more far-flung like Västerbotten or Jokkmokk or Kiruna.’ ‘You’d go to such lengths to spread the Gospel?’ she asked me in a tone that at first sounded like ridicule but afterward, always only afterward, echoed as curiosity. ‘No,’ I said, ‘it’s not that I have such deep religious piety, and the truth is that I come from a Catholic family, but I thought that serving a community was the kind of work that would suit someone like me, and that the Lutheran church in its gracious tolerance would accept me in its ranks, despite my Catholic upbringing. After all, I’m not black.’ ‘Of course not,’ she laughed, ‘and you’re not Jewish.’ At that moment she seemed to enfold me with a boundlessness that spread outward to the ends of the earth. We walked together toward the row of birches and poplars that enclosed the university green, and when we reached it, Maria Madeleine took off her shoes to reveal wide, white feet that contrasted with her willowy frame.”

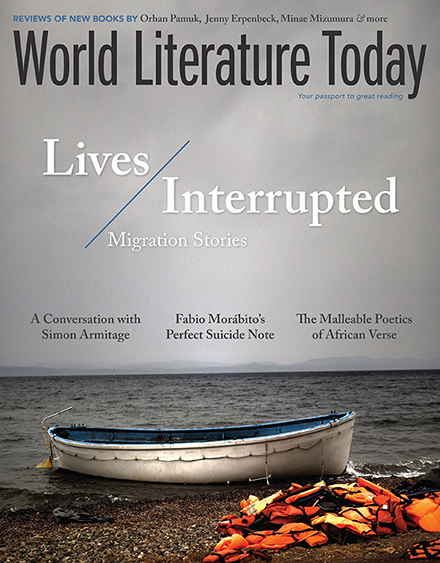

The pastor stopped for a moment and thought a bit, then continued, “Nothing in my life was quite the same again after I met her. Sometimes it seemed to me that my whole life prior to meeting her was a long, deep slumber in which I readied myself for her arrival. You see, I felt as if I’d been saving up my energy to meet her. As we stood among the poplars, she leaned down toward the foxgloves and suggested that we play who-can-spot-a-butterfly-first. As usual, I was suspicious and wondered whether something—and in this case, something indecent—lay behind her suggestion. Perhaps I hoped as much. But she immediately explained that she really was intent on finding butterflies and that, based on the type we found, we could know what sort of summer awaited us. She didn’t know that all my days with her were summer. The first butterfly we found was a dark one, and Maria Madeleine immediately said this was a sign of a rainy summer. Oh, Maria—every sunny summer day brings rain in Sweden. What need do we have for light or dark butterflies?

Only years later did I understand that Maria was a woman who spoke directly, not a woman who dealt in mysteries or innuendo. Her embrace was not a preface to anything else.

“We continued running, or more accurately, she continued running, hiding among the trees, lying down for a moment in the grass only to rise up and frighten me after I was convinced the earth had swallowed her, and one time she hid so well that I stumbled on her body in the grass and fell to my knees. In fact, I would have preferred to have been swallowed by the earth but instead fell upon the body of Maria Madeleine. I was mortified and mumbled a feeble apology. ‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘It really is all right, rather pleasant even. Come here for a moment.’ She hugged me hesitantly but warmly. Only years later did I understand that Maria was a woman who spoke directly, not a woman who dealt in mysteries or innuendo. Her embrace was not a preface to anything else. She simply wanted us to hold one another. And I was happy at the time that I was still so shy that I didn’t dare ask for more, waiting for her to lead the way just as she’d led the way until that point of our embrace, followed by our roll in the grass, and our ramble further and further until the furthest reaches of the day, which in early June knows no bounds and spreads across the entire earth and all the shadowed fjords and inlets, until even the dimness that replaces the day is suffused with a milky light. The sun remained high in the sky and twilight would continue for hours and hours. Then she suddenly said, ‘I need to go. I need to finish an assignment in complex functions for tomorrow. I’m taking a summer course.’

“We lived in entirely separate worlds, our parting always creating a rift between us. Sometimes it seemed as if we existed on two opposite edges of the universe: she with her infinite functions, which she never tired of discussing with the rest of the world, even if we were among friends at a party. She spoke of functions with boundless enthusiasm, explaining their nature and the way they operate in this world and in other worlds, as if they were alive and animate, and not just operations invented by humans for the enjoyment and stimulation of those who work in the exact sciences, while I was caught up in my thoughts about God as they translated into my relationships with the members of the Spånga community, their daily struggles, the immigrants who had joined their ranks over the years, especially those from the Tensta district with their burials, weddings, the baptisms of their children, Sunday sermons, the Christmas holiday, and also Easter, when Maria would abandon me because she believed with all her heart that nothing could overcome the guilt that hung in the air between us during that season of the year.

“That first splendid meeting with her, most radiant of all Jehovah’s days, a great light shone down upon me and I was the happiest of His creatures. She went off. She disappeared into the railway station bound for Stockholm without turning to wave goodbye. I walked away feeling as if I’d had something torn from inside me, and tried to tell myself that until half a day ago I hadn’t even known who she was or where she came from, but a song, or songs, began to well up inside me, some of which I knew the lyrics to and some of which I could only hum a melody to, yet they all fit the words ‘Maria Madeleine, Maria Madeleine, Maria, Maria, Maria.’ I thought I would never see her again. The academic year had ended, and she had traveled by train to Stockholm. I didn’t know her number or her last name, and even if I knew, I was too shy to have dared to approach the department secretary and ask for her number. As the days went by, I sometimes thought I had experienced a vision that could have been called religious, had God or anything holy been involved, but I who was born in sin and live in sin merited only revelation in the form of a woman, some Diana or Lilith, a Jew no less.

Although he was a professor of Hebrew, he never spoke the language, just listened to it and read it, trying to understand while believing with all his heart that Hebrew was the language of God.

“My image of her faded with time, but one morning around the midsummer festivals I stood in the library looking through the writings of Kierkegaard when suddenly I heard her saying, ‘Oh, here you are. I thought we’d never meet again.’ I was speechless with joy. Tears welled up. ‘What?’ she asked. ‘Are you crying?’ I nodded my head. I couldn’t speak. ‘Come, come, let’s go outside.’ She wasn’t put off by my tears. She wiped them away and cried a bit herself, and we hugged again and walked over to the massive birches at the edge of the field. By this point we were walking hand-in-hand. It seemed to me that she was very quiet, as if the boundless energy that enveloped her had dispersed among the splendor of the daisies. ‘Where are you?’ I asked. ‘I’m here,’ she answered, ‘in the infinite. There’s this problem that I can’t solve, and I’ve already looked though all the textbooks, and I simply don’t know what to do.’ I tried to distract her with stories, so I told her about our Hebrew professor, Kronholm, who came from Malmö and was always complaining about the dark winters in Uppsala, and about the fact that although he was a professor of Hebrew, he never spoke the language, just listened to it and read it, trying to understand while believing with all his heart that Hebrew was the language of God. She remained quiet, tense, distant, and it seemed to me that at the conclusion of our meeting she would not board a train but a spaceship and fly far away from everything imaginable. She was so lost in thought she did not even notice the swarms of mosquitos strumming their gold and crystal wings. Our second encounter was much shorter than our first. ‘I really need to go,’ she said. ‘Fine,’ I replied, ‘but perhaps you can leave me a phone number, or a place where I can find you?’ ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I’m in the phone book.’ ‘But what is your name?’ I asked, verging on anger. ‘Maria Madeleine Cohen,’ she said, as if there could be no other name for a young Jewish woman. ‘Lurstigen 4. You’ll find me in no time.’

“That very evening I found her myself, I and no other, aided neither by phone nor post, nor any emissary. I traveled by train to Stockholm and took the 19 bus to Bandhagen. I got off in a neighborhood of immigrants, tall apartment blocks and cultivated beauty, double- or triple-glazed windows, and a foul-smelling elevator rising from the station to the street. I wandered her neighborhood, and the few children I saw couldn’t understand me or perhaps just didn’t recognize the address. I returned to the station, thinking I’d give up, when I stumbled upon a map. It seems I had walked up and down her street a few times without noticing where I was. I went back and this time found my way and then found her. She sat by the entrance to her building observing some cats outside. Now she stood, put her hand to her hair, and said to me, ‘Come, come in, it’s so nice that you came.’ She rounded up her two cats and opened the door for me. We went up a few stairs and entered on the right. Her studio apartment was decorated with Ikea furniture, and Finnish rugs covered the parquet floor. I took in wooden shelves, a table strewn with papers, a large bed in the middle of the room, and a few forgotten coffee mugs resting in the kitchen sink. ‘I wash dishes only when I have guests,’ she said, ‘and I didn’t know that you were coming.’ I already knew that she wasn’t the domestic type. She was more at home in the forests and fields than in orderly furnished rooms. ‘This problem,’ she said, as if we’d both been working on it, ‘has to be dealt with in two-dimensional space, not in infinitely many spaces.’

“She was once again lively and animated, and when she hugged me this time I sensed how thin her bones were, and I felt her arms and legs that had grown wild with the hair she never bothered to remove. But afterward, when she hugged me again, she said, ‘You’re not at all Jewish.’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘not at all.’ But her father was a Communist from Birobidzhan who referred to the Land of Israel as Palestine and refused even to visit unless historical wrongs were righted and so on and so forth, so why did she care that I was ‘not at all Jewish?’ ‘No,’ she said, ‘I don’t care, nor do I care about your affairs with God, or with whatever does or does not exist, but there are some people who are Gentiles in their heads and Jews in their pants, if you know what I mean.’ And in order to bolster her conviction, which became firmer with time, she would visit me here, in Spånga Church, where I did my pastoral training, and she sat in the Jews’ pew, and would sit me down there as well. We perched at a distance from Mona, the minister who served in the church before I took over, while she blessed our Jewish guests, a custom that I continue to this day: Bernt Jakobson and his children, Mimi and Elias, Stefan Bruchfeld and his wife, Anita Karp, who has had a soft spot for Jews ever since her first marriage, and Peter Forslund and his four children, Emmanuel, Anna, Gabriella, and Eva, who are not Jewish at all and whose father also isn’t Jewish, but on account of his love and affinity for Jews he became more and more like them and now feels comfortable among them even in church.

“‘Maria Madeleine,’ I said to her, ‘I’m a grown man. I’m not a baby. Have mercy.’ In spite of her name, when it came to this matter she had no compassion. ‘Didn’t you read your Kierkegaard? Haven’t you heard of Abraham the patriarch? Do you know what age he was when he did it?’ ‘Yes, Maria Madeleine, I know, ninety-nine, but it’s inhumane to demand that from me. I’m not Abraham, but if that’s what we’re talking about then listen for a moment: do you remember what the angel said to Abraham just before he nearly sacrificed his son, his only son, whom he loved? He said to him, “Do not raise your hand against the boy or do anything to him. For now I know you fear God.” The God of the Jews is a God of intentions, Maria Madeleine. Please, I beg you.’ ‘Fine,’ she laughed, ‘But I’m not God, and I’m not asking you to sacrifice your son, only something much smaller.’

“This wasn’t empty talk; Maria Madeleine was a doer. From the day she decided to convert me from the waist down, things became increasingly complicated. On the surface, we looked like a couple. I moved my very few possessions from my dormitory in Uppsala into her apartment in Bandhagen. On the Jewish new year, which generally falls in September, we went to her parents’ home in Skarpnäck, where we ate sweet patties of fish garnished with carrot, which was surprisingly delicious. Her father mumbled some blessings, which included a few words that I recognized from Professor Kronholm’s classes, though her father seemed to have no idea what they meant. On Christmas, we went to my parents’ home and my mother knit a pair of socks for Maria as a present, and made her a special dish that had no pork in it, since she remembered that this is something that Jews will not eat. But Maria Madeleine said to her, ‘Thank you very much, don’t trouble yourself, I actually do eat pork. It’s not the flesh that determines whether you’re Jewish or gentile.’

“‘Oh, Maria, then why do you care? I promise to accompany you everywhere with my pants on. Who will know?’ She laughed. ‘That’s something else entirely.’ ‘OK,’ I said to her at the beginning of March. ‘You want blood? I’ll give you blood.’ It was at the height of winter, a winter of fasting and supplication. ‘Where does one do it?’ ‘There is a doctor who operates on Jews and Muslims in the hospital in the south. Dr. Lazarus. He’s a pathologist by training, but he’s an expert in his field. I’ve seen some of his work,’ she said. ‘Call, make an appointment, just do it. Of course, there is also the guy who does ritual circumcision for the Jewish community, Gerber or Berger. But he does it in the synagogue with a live audience, in front of the whole congregation. Also, he’s terribly slow.’

In my despair, I searched the phone book for the association of eunuchs, but none of them could help me because no such associations existed, or at least they didn’t advertise their services in the phone book.

“I don’t think I’ve devoted as much time paging through Holy Writ as I did to paging through the Stockholm phone book, especially the medical listings. The idea tormented me day and night. I imagined a crowd of Jewish doctors hovering around me, their flashlights focused on me, with knives in their hands and one singular goal in mind. ‘Look, Maria, if an accident happens, or if someone takes a small baby and inflicts this on him when he can’t protect himself, it’s very cruel, but that’s still much easier than asking someone else to do it to you.’ ‘It’s nothing,’ she insisted, ‘trust me. The recovery is quick. All my Jewish friends told me how it went with their babies.’ ‘But I’m not a baby! What are you going to ask of me next? That I throw myself under a subway train?’ ‘Hardly, and if you weren’t such a baby, you’d have done it already.’ Sometimes her patience would wear thin and she would exclaim, ‘If you don’t want to do it, then don’t. I’m not forcing you.’ But in general she had the characteristic obstinance of her ancient stock. They have all the time in the world. They were here first, and perhaps they’ll be here last. I was very much alone. How many people have gone through an experience like this? In my despair, I searched the phone book for the association of eunuchs, and the association of the disabled-by-choice, and the association of survivors of suicide, but none of them could help me because no such associations existed, or at least they didn’t advertise their services in the phone book. In a halting call, I appealed to the Jewish community. The secretary who answered the phone recognized my voice and said, ‘Hello, didn’t we meet in synagogue on Yom Kippur? You’re Maria Madeleine’s boyfriend who studies theology in Uppsala. I recognized your voice. You have a magnificent voice—you’ll be a wonderful pastor.’ After that, I couldn’t ask her anything about becoming a Jew, though my mental anguish and tormented thoughts caused me more suffering than any other part of my body.

“‘Yes,’ Dr. Lazarus said to me. ‘Yes, of course. I’ll be working on Friday, April 13.’ The appointment was made for that long Friday in the Sophiahemmet Hospital next to the Technological Institute of Stockholm.

“Maria Madeleine responded with a mild pleasure that did not match the tremendous anxiety that beset me. ‘Wonderful,’ she said. ‘You’ll see, afterward you’ll feel completely different.’ I had no doubt.

“We were married in city hall as soon as the wound had healed, and the excitement I felt anticipating our wedding night was like that of an abstinent monk; indeed, I’d been an abstinent monk since the previous summer. But I only slept with her one more time, the night after the morning of our marriage. After that, my strength failed me in every respect.

“I divorced Maria Madeleine Cohen shortly thereafter. I couldn’t bear the burden of my memories and the pain bound up in them. They tortured me more than any knife that had ever cut into my flesh. I was alone for a very long time, and to this day I drunkenly remember that happy day in Uppsala at the beginning of the summer and how far we walked that evening. I have never loved nor will I love any woman the way I loved her.

“But since I have become a Jew in my pants, I have grown close to the Jewish community, as if compelled. I attend synagogue on the high holidays, listen to the sermons of Rabbi Edelman and occasionally those of Rabbi Narrowe, and that is how I met Liza Nuemann, who married me and who gave me, to my great joy, two daughters but no son.”

Translation from the Hebrew

By Ilana Kurshan