May the End Be Well for All

The tradition of toast-giving has followed my family through centuries and continents. This essay tells the tale of one family’s survival and the toasts—poignant and amusing—that have brought together generations in grief and celebration.

The best place to lose our wiggly teeth was under grandma’s queen-sized dining table, with a mouth full of grilled pork and fresh blood. It was there—veiled by the ivory of her vinyl tablecloth, alongside the dressed feet of our guests, beneath a spread of regal fodder—where childhood happiness dwelled. There, we whispered secrets. There, we pursed stolen cigarettes between our lips. There, we swapped pigeon feathers and sniffed foreign bubble gum wrappers. There, we untied Uncle Rob’s shoelaces and counted the stitched holes of Aunt Rosa’s nude hosiery. There, we raised our plastic mugs with tarragon lemonade and said toasts: To the boys we loved loving us back! To living till one hundred! To meeting Michael Jackson!

Unlike us, the Armenian adults above our heads never ran out of toasts. Suddenly, with a shot of amber cognac in his hand, the most quivery relative turned into a veteran orator, and the most mousy neighbor metamorphosed into a philosopher. Kenats cheers echoed as crystal glasses clanked. First to the kids—their beloved, mannerly kids who, at that very moment, unbeknownst to them, underneath their rice pilafs and roasted eggplants, were snickering noiselessly behind their hands. Then, to the mothers who had birthed them. Then, to the matriarch who had cooked the feast and the patriarch who had followed his wife’s instructions to the last herb at the morning market. Around the fourth toast, they drank to those who had fled death at the turn of the century. After all, they’d say, we were all there—under or around the table—because they had survived. By the grace of God, by the kindness of strangers, they had survived. That was when our whispers would mute, our hands would fold on our laps, and we would listen—partly with awe, partly with guilt from eavesdropping on stories that weren’t meant for our young ears—as their toasts came alive in full color in our imaginations.

I pictured her to be a beauty, my great-great-grandmother. Not the kind with eyes blacker than the midnight heavens that turned heads in crowded village bazaars, but the kind that came from astounding strength. The kind that was tender and formidable all in one breath, making you feel safe even amidst the most savage circumstances. The kind that belonged to a mother. Oh, the madness she must have witnessed as she fled with her remaining kids on her back toward the heart of eastern Armenia, they’d bewail in their toasts. Oh, the farewells she must have ordained; the hopes she must have slaughtered. Oh, the will it must have taken to barter all that was sacred for the next breath, they’d commend, as she ran with her sons through ravaged villages and bare hills under the cloak of the mournful nights that knew no end, coming to the brink of death time and time again, only to be sent away to taste more grief. Some would survive. My great-grandfather was among them. It was his eyes, they’d conclude, his still like the summer skies blue eyes, that betrayed him. They glinted with scraps of sorrow that no amount of cheer was ever able to dim, even when a smile would stretch under his white beard.

By the time we would crawl out from underneath the tablecloths, by the time we would realize that the toasts we heard weren’t merely ceremonious preludes to the next shot of liquor, the adults would no longer be sitting around the table. Neither would we. By then, we would be on our way even further east, even closer to the sun.

We hear the hum—the murmur of their memories, the cheer of their toasts, the cries of their lost friendships—because it’s coming from our own hearts.

Japan was far from home. It was too different, despite the fact that our earths shook with as much fury and our foods tasted of equal magic. Yet we took off our shoes, unpacked our bags, clasped our hands around our new green tea mugs and watched the pastels of the cherry blossoms turn the burning red of autumn maples. We waited and waited, with a mélange of nostalgia and enchantment that comes with new beginnings, for time to churn the foreign into familiar, the alien megalopolis to home. All the while, we found ways to keep our native land, now oceans away, closer than ever. We spoke Armenian at home—even when the narrations of our dreams peppered with Japanese words; and stewed meat in grape leaves—even if we used chopsticks to eat it. We colored eggs in April. We unwrapped our New Year’s gifts when Grandpa Winter brought his presents to all the other Armenian kids. Then, we said toasts. Toasts, that once in a while would allude to our ancestors and the slivers of history that they had carried in their empty pockets on the move. Later, when our eyes would get used to seeing the white head of Mt. Fuji instead of Mt. Ararat’s snow-capped crown, our toasts would get shorter. Less sentimental. More ascetic. To peace, we would say, raising our sake cups to a chime of reticent Kanpais.

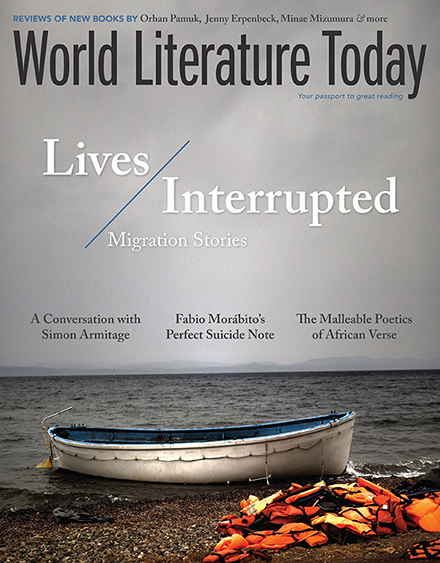

We don’t say Kenats or Kanpai anymore. It’s mostly Cheers or Prost now, and it’s always to the health of our own children. Outside our windows, the European streets are surging with the hum of a thousand moving feet. We hear the hum—the murmur of their memories, the cheer of their toasts, the cries of their lost friendships—because it’s coming from our own hearts. Movement is in our bones. Some of us move for love. Some for work. Others move from war. Some move in caravans. Others alone, carrying their stories on their backs like tireless snails, following foreign road maps to a home that they hope will be warmer than the one they left behind. As we watch them move, we marvel at the continuity of our narratives, at the common thread that runs through our migrant fates in the most surprising ways, weaving blueprints of infallible grace. Then, we turn our eyes back to those sitting around our tables, as our children play with our shoelaces at our feet. And we raise our glasses, only to repeat the words that we memorized as kids under Grandma’s vinyl tablecloths: May the end be well for all.

Amsterdam