The Power of Normal: Exploring the Notion of Story Structure

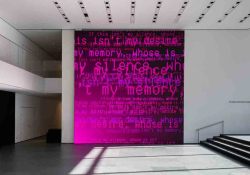

As readers, we all carry prejudices, but acknowledging a wider range of normals makes the difference between “I don’t understand your normal” and “I refuse to recognize your normal.”

A

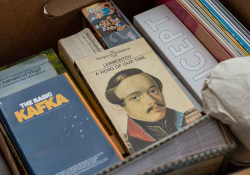

s another year gathers speed it strikes me that I have been teaching creative writing in some form or other for over a decade. In that time, I have encountered numerous theories on story structure and narrative conventions; from Gustav Freytag’s Pyramid, to Three-Act structure, to the Hollywood-adored The Writer’s Journey, by Christopher Vogler, which was itself derived from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, to Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots. In my own practice, I avoid teaching these analyses as guide models. Each time I refer to one of them, I make it a point to stress to my students they are not universally true and should always be challenged.

My discomfort with these 3–5–7 models (as I like to call them) is not just from the absurdity of trying to distill the complexity of the world’s eternally evolving heritage of stories into single models, which invariably are littered with caveats and exceptions. No. My bigger concern is that the 3–5–7 models have largely also become foundations for exclusion of certain stories—and the focus on models is somewhat akin to the way in which global economists spend years arguing about which capitalist models work better, without giving any attention to the fact that all successful capitalist nations were built on inhumane exploitation of serfs, women, occupied lands, slaves, children—and in more recent success stories like Singapore and South Korea, underpaid labor and suppression of civil liberties. Just as it is within the world of fiction, focusing on the economic models and not the historic biases and nuances is misleading.

Strangely, nobody seems to question the normal, but writers and storytellers from the margins will have been affected by it without the word ever being mentioned.

What the 3–5–7s share is the notion of the normal; the starting point and, often, the conclusion of stories are deemed as normal—what happens in-between is upheaval, the drama. Strangely, nobody seems to question the normal, but writers and storytellers from the margins will have been affected by it without the word ever being mentioned. They will have been told that their stories aren’t relatable, compelling, structured, of high enough quality, etc. And while these things may be true sometimes, often what gatekeepers, fully schooled in the 3–5–7s but not the prejudices underlying them, are saying is, “I don’t recognize your normal,” or, more authoritatively, “I refuse to recognize your normal.” So, essentially, what much of the world does is to learn the dominant normal and judge stories by that capitalized Normal. That way the focus shifts to Vogler versus Booker, or the relevance of newer perspectives from the likes of John Yorke, a former producer for the cult British soap EastEnders, whose book, Into the Woods, purports to answer the why of storytelling, and Dan Harmon’s story embryo, on which his successful TV series Community is based, that argues for eight stages: (1) a normal world, (2) a desired object, (3) entry into a new world to acquire the desired object, (4) adaptation to the new world, (5) reaching the desired object, (6) paying the price for it, and (7) returning to the normal world having (8) changed.

These are all useful perspectives, but the question of What is Normal? remains unasked. It lurks in the background like any other kind of institutionalized prejudice. We all carry prejudices, but acknowledging a wider range of normals makes the difference between I don’t understand your normal and I refuse to recognize your normal.

If I count my work from school magazines in Ghana, I have worked as an editor for thirty years, but in every week of those years I have encountered new variations of normal. Particularly memorable was an incident when I was working in-residence at California State University, Los Angeles. I was reading a collection of stories by a Chinese writer, Mu Xin, called An Empty Room. The writing was evocative, competent, and poetic, but I felt distant from it. Luckily the translator of the collection, Jun Liu, a Faulkner scholar, also worked at Cal State LA; I spoke to him and he explained the influence of sanwen—a Chinese genre that blends elements of essay, poetry, and fiction—on the work of Mu Xin. Suddenly, with the context of another normal, my reading of the stories changed; An Empty Room became a book I could love, the author’s craft a masterful thing to admire.

What’s interesting in that scenario is that the book was already published. However, if I were the editor it was submitted to for consideration, my notes would have been interesting—to say the least—simply because the age-old sanwen was not within my vocabulary of normals. What’s crucial is that my vocabulary of normals works both ways—affecting what I accept and what I question. Thus the dominant Normal can potentially impoverish readers. For example, in many parts of Latin America and Africa, a big family is a nonstory, one of many ways in which people exist, but in the world of Normal, it is exotic and its use is “accepted.” This makes something that is just one of many possibilities a marker of authenticity for an entire region, something that provokes questions when it is absent. It is the same approach that gave birth to the epidemic of poverty porn from Africa.

What’s crucial is that my vocabulary of normals works both ways—affecting what I accept and what I question.

Therefore, the power of transformation in storytelling, for me, is in the construction of Normal—and, on a sociopolitical level, it is interesting to observe who is allowed to shift Normal. It is no coincidence that there was a growth of interest in Hong Kong cinema after the emergence of Quentin Tarantino. As a white American male, his work normalizes stylized graphic violence, adding it to the vocabulary of the dominant Normal. That shift opens the door for several US remakes but also original Hong Kong films to become successful, their quality suddenly self-evident.

Where the marker of convention sits on the scale of the dominant Normal determines what is considered realist, magical realist (you’ll find many writers labeled as such reject the idea), romance (based on what is accepted as a happy ending), gangster (where vengeance is normal), etc. If your normal is not present within the lexicon of dominant Normal, whatever world you create is subject to question, your normal can be refused, and you are left on the periphery. This is how the American novel was considered inferior to the British novel in the nineteenth century, because Great Britain at the time was the center, the arbiter of taste; G. K. Chesterton jibes in one of his Father Brown narratives, “One of his hobbies was to wait for the American Shakespeare—a hobby more patient than angling,” and Sydney Smith asks in a January 1820 issue of the Edinburgh Review, “In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?” Novels from America were largely dismissed by British critics as sentimental and lacking in literary quality; Russian works of fiction were seen as curiosities.

If your normal is not present within the lexicon of dominant Normal, whatever world you create is subject to question, your normal can be refused, and you are left on the periphery.

As the center has expanded, America and Russia have become part of the larger Normal and have thus qualified to be spoken of in the realm of quality. I was actually told in one class how to read a Russian novel, and, of course, Vladimir Nabokov famously published Lectures on Russian Literature in 1980. Until your normal enters the grand hall of the dominant Normals, however, you are subject to some editor saying your well-researched, meticulously crafted work, which anyone who knows anything about your normal thinks is extraordinary, is just not relatable, compelling, structured, of high enough quality. . . . You are an Aborigine, you are a rural Nicaraguan, you are any number of minorities. You are outside the gates and neither Vogler nor Booker nor Yorke can save you. That is the power of Normal.

Accra