Favorite Hong Kong Foods

Tammy Lai-Ming Ho

Sweet and Sour Soup

Some years ago, I visited Luxembourg, and when I went looking for somewhere to eat in the area around the hostel I stayed in, I found there wasn’t much in the way of restaurants. Luckily, I stumbled upon a small Chinese place called Jin Fu. It was hardly overwhelmed with trade—while I was having dinner, there were a handful of locals drinking at the bar and not many other patrons. I decided to have a set meal which included a sweet and sour soup, spring rolls and a chicken dish with Chinese mushrooms and bamboo shoots.

I had an uncanny sensation tasting the soup, comparable to that experienced by Proust’s narrator when biting into his madeleine. It reminded me of the kind of soup my late grandmother used to make, and I couldn’t hold back the tears. I could never have imagined someone else would be able to concoct the exact same flavour as she did: the subtle taste of sweetness and sourness, the whipped eggs, and the same assortment of vegetables. Perhaps the traditional Chinese music played in the background helped foster this sense of nostalgia in me. A musical note, a taste, a smell—the smallest things can conjure up the deepest emotions. The following dishes were equally good, the spring rolls huge and crispy, the ingredients ringing with freshness; the chicken I had was sumptuous, far better than I expected for a neighbourhood Chinese restaurant in a relatively obscure European city.

While I was eating, the owner and then, later, the cook came out to talk to me. When I complimented the cook on his food, he was very happy but was also a bit shy. He explained that it didn’t matter how well he cooked, people in the area only came there to drink. When he left me, he said, “We Chinese eat things hot, so I’ll let you finish your meal.” I remembered how my parents used to reprimand me for eating too slowly. I left the restaurant both heartened and sad.

Kit Fan

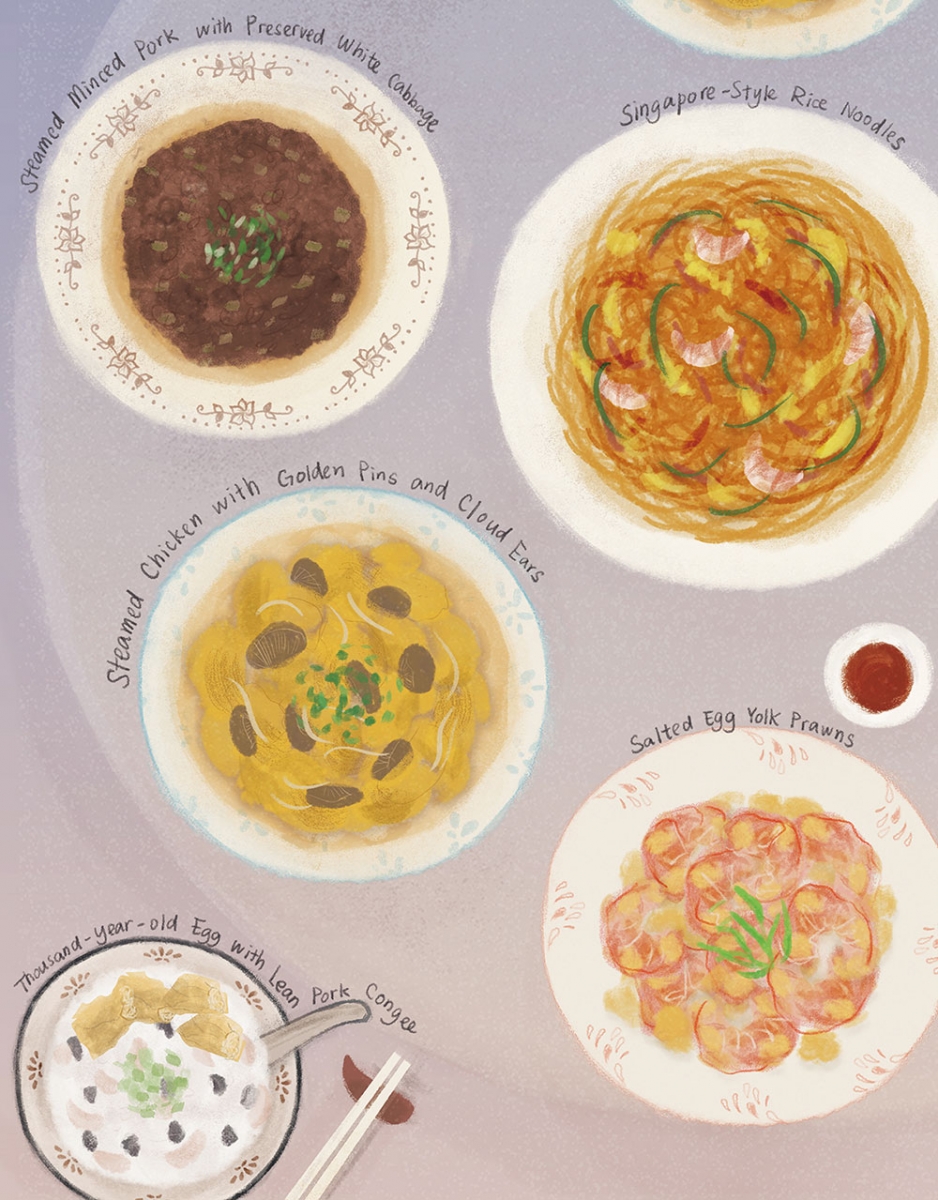

Steamed Chicken with Golden Pins and Cloud Ears

This sublime Hong Kong dish is food for the gods but for us humans too. Golden pins and cloud ears are mushrooms that resemble their names. Often sold dried, but once rehydrated they are transformed back into their true form of subtle hues and textures. As the hot steam circulates in the wok like a Turkish sauna, the autumnal earthiness of the mushrooms accentuates the soothing sweetness of the chicken thighs, tempering each other to create a humble yet otherworldly dish that should only be savored with a pinch of chopped spring onions and a drop of sesame oil.

Jason S. Polley

Tempe and Squash Hot Veg Curry on Red Rice

Most Hong Kong markets feature an Indonesian shop. Arrive before noon and you’re likely to find 500g cubes of tempe in stock. These compressed soybeans continue to ferment for days in their plastic wrap. Carréd, coconut-oil fried tempe supplemented with carrots, butternut squash, Spanish onions, a bulb of garlic, several green chilies, curry paste (Thai, Malay, Indian, or Cantonese), and coconut milk, in that order, brought to a near boil, then scooped onto a bed of Cantonese red rice and topped with fresh diced tomatoes, cilantro, and scallions, as well as a dollop of yogurt, a tablespoon of sour mango pickle, and a teaspoon of Japanese hot chili pepper, complemented with a quart of icy Laam Mui beer, is a savory ally to Sunday sunsets.

Jennifer Wong

Soup Macaroni / Steamed Milk

When I was at school, my classmates and I frequented the Australia Dairy Café in Jordan. You can never miss that restaurant on Parkes Street, marked by its insanely long queue of diners from morning till night. We have always seen it as a place for “Western Café Food,” only to realize that their hugely popular dishes—soup macaroni with cha siu, the city-famous steamed milk—are simply Chinese ideas of Western meals. The service is unbelievably Chinese: you have five seconds (or less) to think about what you like to eat, and expect the dish to arrive in no more than ten minutes! It feels like a timer is ticking away on your dining table once you are seated. But the restaurant is always heaving, and we all leave the place contented, satisfied with that perfectly-cooked macaroni in soup, or the steamed milk dessert that replenishes the skin.

Kate Rogers

Chicken and Vegetable Stir Fry in My Hong Kong Wok

Canola oil heating in the broad basin of the wok turns steel the color of brass; carrot chunks and baby corn soften. I lower the flame to protect broccoli’s green crunch, raw chicken strips. With my wooden spatula I turn the chicken’s pink flesh until it’s white, then golden brown. Sliced mushrooms and finely chopped garlic, ginger and onion simmer in chicken and vegetable juices, dark salty-sweet oyster sauce. I serve my stir fry with Taiwanese brown rice. I’ve seen white and brown ducks paddling among fresh green rice shoots outside Hualien. I think of them as I cook stir fry.

Arthur Leung

Steamed Minced Pork with Preserved White Cabbage

An all-time favorite for a lazy but always hungry person like me, which contains everything in a single and easy-to-make dish—meat (for protein), vegetable (for fiber) and flavorings including salt, sugar, fat and ginger giving a taste rich enough for me to go with two big bowls of plain rice. I have been obsessed with the unique taste of preserved white cabbage ever since I had memory, notwithstanding its unappealing look.

Eddie Tay

Poon Choi

My favorite food in Hong Kong is definitely poon choi. It’s certainly not homecooked food, though you could pre-order it at restaurants and bring it home on festive days. I like it because nobody eats poon choi alone. My first experience of poon choi was family day organized by the Hong Kong Scouts Association. (My son was a scout.) The last time I had it was at a village banquet in the New Territories during the Lunar New Year festivities, while watching a lion dance performance. Poon choi is really something unique to Hong Kong and certainly not found in Singapore.

Lian-Hee Wee

Singapore-style Rice Noodles / Steamed Egg

Singapore-style fried thin rice noodles, written as ✰米 in Hong Kong kitchen shorthand to stand for 星洲炒米, where 星 ‘star’ is pronounced sing. Not available in Singapore, this is a highly popular dish in Hong Kong eateries where curry powder is added to create the Southeast Asian food stereotype. Not normally prepared at home. Second, steamed egg, written as 水旦 in Hong Kong kitchen shorthand, is a home dish also served in low-end Hong Kong eateries. In Singapore, my mother made this occasionally for lunch when I was little. Now, my wife makes it whenever I have that “I hate school” look on my face. This modest food item connects me to both my homes in the two cities.

Belle Ling

Salted Egg Yolk Prawns

These prawns—covered in battered preserved duck egg yolk, with its texture sandy and crust golden—are my favorite dish. My mother avoids red meat though my brother likes it, my father inclines to dislike fish, and I cannot stand the heavily rich taste of chicken, especially that of the Cantonese “white cut chicken,” which is slightly boiled leaving some blood on the bones. The more palatable meat in my family is prawns. And salted egg yolk in a Chinese family is a “cure.” Too poor to have meat? Add a salted egg yolk into your rice porridge. My mum said that in her puberty she could empty three bowls of jasmine rice with just two salted eggs. Eating mum’s salted egg yolk prawns, our mouths are full moons, the yellows are velvety and contented.

Wawa

Pork and Vegetable Cake

My mom’s recipe of minced (*fat) pork and preserved vegetables (*from Tai O only) “cake.” The sound of my mom chopping the blended mixture always made me restlessly energetic. My fetish of perfectly savoring this delicacy was to have it perfectly evenly distributed in rice with a perfect portion of it scooped out from dish to bowl. That means mixing approximately two or three grains with a small lump (1/3 of a fingertip) of this “cake” for the whole bowl. It always took ten minutes to meticulously mix the bowl but less than three minutes to devour it ferociously. My mom believes that this is the source of my twenty-year stomach ailments, however. When I grew up, my mom was not around. So I made it for myself and realized how tiring it is to chop that goddamn mixture in order to make that happy sound. Now it always has to be a relay between me and my husband to make this cake. Yes, it’s a farmer’s dish—my mom grew up starving in a poor peasant’s family, so probably this was her delicacy too.

Chris Song

Lemon Coffee

My favourite Hong Kong drink is lemon coffee, which is very common in any local cha chaanteng. It is a cup of black coffee with lemon slices in it, so it tastes sour and bitter. Since college days, lemon coffee has been my comfort drink whenever I catch a cold. It is said to have been derived from the Italian expresso romano, but nobody could prove it. In this respect, lemon coffee could be seen as a symbol of Hong Kong culture, which transforms foreign influences into its own cultural specifics that were able to present its unprovable identity.

Xu Xi

Thousand-year-old Egg with Lean Pork Congee

I have written about this basic dish before, one you can eat for breakfast or late at night, sometimes after hours, when it’s time to 消夜, to “digest the late hour.” It is the most Hong Kong taste on my tongue, and probably always will be. In my ekphrastic essay collection Interruptions, co-authored with photographer David Clarke, I responded to his photo of a congee restaurant sign. This brief excerpt from the essay will perhaps demonstrate the lingering sensation this dish always conjures for me:

I cannot recall the first time I tasted Cantonese juk, the rice porridge that is indecipherably translated as “congee” . . . Juk, or congee, especially with lean pork and thousand-year old egg, accompanied by a 油 條 fried dough stick, is my best breakfast. In fact, it is the only breakfast that, for many years, I willingly ate, always at a restaurant or Hong Kong congee-house, identified by 粥, usually in red on the shop-front window. A visual spectacle: the character rice (米) is tucked between two lovers. The best juk I’ve ever tasted, however, was at a roadside stall in Central, the only one open at 0400 hours after too much wine and music and conversation at a jazz club. The night’s refuse faded into the periphery around my feet, and the steaming juk, ladled by the chef from his wooden cauldron, eased me into that morning. That was over a decade ago, the jazz club is long gone, but the juk is probably still there. (from “Breakfast,” in Interruptions, by David Clarke and Xu Xi, 2016)