“And Leaving from the Crowded City”

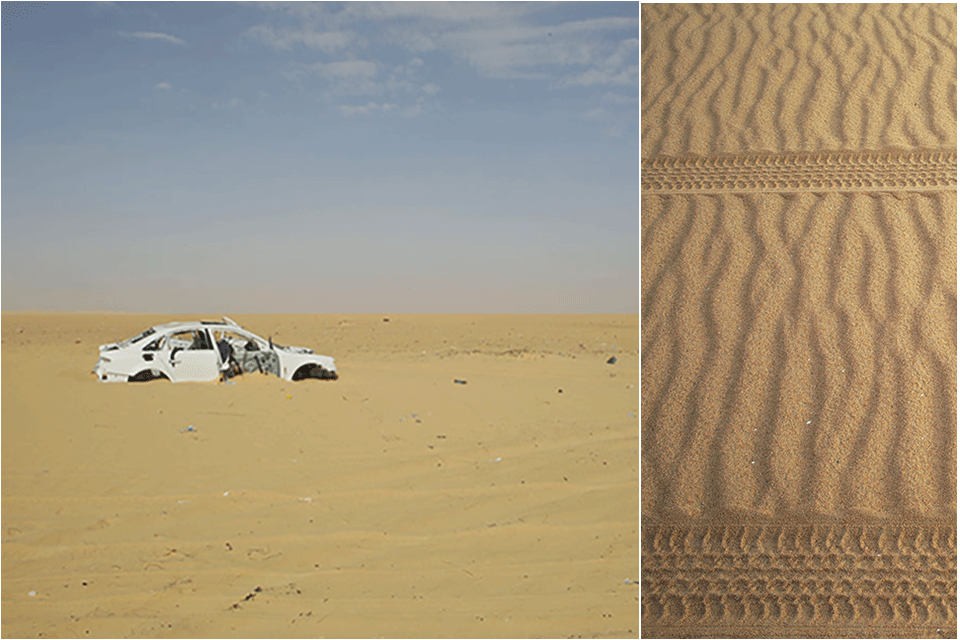

RIGHT Vehicles pause during the hottest hours to avoid stressing the motor and shredding tires. PHOTOS: Ladan Osman

As her journey begins, Ladan Osman accepts her partner’s invitation to travel with him to the Sahel. One of few women there among a group of journalists, she finds herself “several times the guest in Niamey.”

In late July 2018 the looped recording of a frog’s croak plays through the night before my tenth move since arriving in New York two years earlier. Although it’s a comfortable sublet and I have no reason to leave, I have no confirmed means to stay. I need a break from the US, the home whose welcome seems retractable. The air warms, but I find myself indoors trying to avoid xenophobic street harassment. The only respite from hateful commentaries is the occasional shout of “Wakanda!” when a fellow black person, usually an elder, notes my wax-print jumpsuit. I accept my partner’s invitation to travel with him as he reports on migration in the Sahel, and spend most of my deposit on a plane ticket to Niamey, Niger. The day I leave, I note an Arizona tea bottle sitting in the laundromat window. I blink away the photograph of Trayvon Martin’s prone young body, my dread of that image superimposing on the pavement in front of me. It really is time to go.

When hurtling through the night over the murmuring Black Atlantic, I’m most aware that homeland lives in a future.

A phrasing in Leontyne Price’s rendition of “Un bel dì” from act 2 of Madama Butterfly sounds how I feel when preparing to cross the Atlantic. E uscito dalla folla cittadina (And leaving from the crowded city), she sings, trilling against melancholy, her anticipation dense. This journey represents two freedoms: going and planning return. I revisit the relationship between the ocean and clouds, shadows creating a lattice on surface water. When hurtling through the night over the murmuring Black Atlantic, I’m most aware that homeland lives in a future. There’s always a moment I startle awake, my thoughts at first a dark velvet, textured but blank. I’m unable to sleep over Malta. I take two blurry photographs of our flight path, the terrible mathematics of this water trembling my hands:

On October 11, 2013, a fishing boat begins to take on water. There are 260 exiled people on board, trying to reach Italy. They’re sixty-one miles away from the Italian island of Lampedusa but inside the territorial waters of Malta, which is twice the distance away. A Syrian doctor named Mohamed Jammo radios for help, saying: “Please hurry,” and “The boat is going down.” There are sixty children on board. Dr. Jammo calls the Italian Coast Guard to ask if they have sent anyone and is told to call Malta. Malta refers him back to the Italian Coast Guard. Dr. Jammo (“Mr. Jammo” in some news articles) says: “We are dying, please.” The operator repeats: “You have to call Malta, Sir.” Meanwhile, an Italian Navy patrol boat is less than twenty miles away. Five hours later, thirty-four people drown. The articles don’t specify how many of the dead were children, which is strange because writers are careful to note how many were present.1

* * *

I'M SEVERAL TIMES THE GUEST in Niamey. A black stranger in a black country, shy to speak French, scrambling to be of use while staying out of the way. Most people say: “Even her?” when we’re introduced as Americans. “We’re journalists,” my partner says graciously. “I’m just a writer,” I correct. Often enough, I don’t have to say anything. There are very few women around, and sometimes a pointed lack of acknowledgment when I enter a room. Researchers, officials, NGO workers, and residents discuss migration across the Sahel, each perspective reflecting one’s history and economic stake in the situation. Officials follow the narrative line set by European Union developmental activities, backed by a pledge of one billion euros.2 There are fact sheets and slideshows and maps attempting to demonstrate transit routes, the perils of passage, and the region’s will to cooperate with the EU’s antimigration objectives. The region has become a kind of fulcrum under pressure. A massive influx of people traveled to Libya after the 2011 civil war and intervention, and Niger is now a nation West and Central Africans travel through on their ways home. The policing of borders changes how people access neighboring countries. Movement is restricted in an attempt to curb populations before they reach Libya or beyond, whatever the intention of the traveler.

The region has become a kind of fulcrum under pressure.

Long-established alternative economies that support trade and inter-African travel for temporary work collapse. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), eight hundred thousand migrants fled Libya during the 2011 crisis. The 2018 World Migration Report quotes a Daesh threat that it would “flood Europe” with half a million refugees through Libya. A disturbing ebb and flow of humans suffering due to economics, conflict, and climate change, their bodies transmuted into a desert sea. As migrants move north, the EU shifts its attention south, influencing policies to protect its interests. It quickly becomes hard to see how these funds develop anything except harried immigration strategies in a region that largely resists the motivations informing them. Before leaving New York, I watched men play the board game Risk, their bodies hunched over Africa. This retrieves another memory, held in a keepsake box I don’t want, of a student’s final video project: she and a friend hopscotching over transatlantic slave trade routes.

Before leaving New York, I watched men play the board game Risk, their bodies hunched over Africa.

One evening in early August, we wait to meet migrants traveling by bus from Agadez. They’ve already taken a hard road from the Algerian border and will continue on to their home countries. A local bus company has secured a contract to assist the IOM with voluntary repatriation. Although I don’t ask about it, I wonder how they won the contract, if the process is as corrupted as the one that selects private companies to service prisons and charter schools in the US. We’re in a large courtyard, empty save a neem tree and two open-air structures swept clean, sleeping mats stacked in the center of one. I hear frogs again, now real, and have the sense of being driven to a place, being prepared for it. I skip Whitney Houston’s “Heartbreak Hotel” when it starts to play, then remove my earbuds altogether. Rain falls as the first bus arrives. By the end of the night four hundred people from Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Nigeria will pause here. They’re mostly young men, so few women and children it seems as if a biblical event has passed through them. I try to imagine the places the men and boys left full of women and girls. One of the youngest travelers is alone. He seems eleven but says he’s sixteen, his voice high notes in minor key. He wears a bleached streak in his hair, after the soccer player Paul Pogba. A woman traveling with her toddler asks me to help her secure a covered place to sleep. Before I can respond, a teen says: Look for space in your son, and a cautious argument begins.

Refouler, they call this process. In a warped translation, it sounds akin to: make a fool again. What does it mean to return, against your original intention? To approach return as rescue, heart-hurt by your reluctant forfeiture of hope for success? The journalists must again and again clear the justified and unmistakable air of mistrust. The one from Agadez is approached with familiarity: Democracy? I hear him say. We’re here for the people’s story, which is universal. I hear most stories and their echoes, my understanding of French outpacing my will to speak it: Two cousins leave home at different times and tonight head home together. One explains how social media informs the decision to go: You see images of friends settled, well dressed, not people trying to get to Algeria five, six times. They deport blacks, paper or no paper. He describes Facebook as an absurdity, a dangerous deceit, laughing a little: I saw my cousin taking selfies, in fresh jeans, looking nice. Outside the photo; no work, no entry, no way to return home. It doesn’t take long for my lack of experience to show. I’m inappropriately speechless and bruised, ashamed to write anything even as a few teens jostle and joke: Me! No, me, I’m the chief of beautiful stories. A man with many toothbrushes and bottles of water offers to share. The present slips into a past, located in the lobby of an Ohio public housing authority building. There, I was a girl. When the case manager called an elder to follow her, his toothbrush fell out of his backpack. I tried to offer something with my eyes. The expression in his glance remains inscrutable. Tonight, here, I’m failing in the same way.

The courtyard is nearly full after only two buses. At first, people appear bashful as they step over each other. Hours later, shoes line the far edges of the floors, barely out of the rain. Before we leave, we sit with teens who shift to ask us questions about the purpose of this news story. A teen with loose curls, nicknamed “Don Carlos,” wears a Bart Simpson T-shirt. America has Marines and Snoop Dogg and free college, he says. They signify, notating new strains on a diasporic libretto, and I don’t lose the nimble critiques layered into their banter. When they ask about the cost of tuition and health care, their silence around those sums reveals a possibility has been taken away. Their silence recalls the surly dejection that had settled on my Chicago high school English students the October morning they came in discussing Gaddafi. They struggled to articulate why they found his death and its imagery personally humiliating, but a notion that their seniors had somehow failed them lived inside their wordlessness. There, and here, the youth shrug off disquiet. Attempting ascent while reckoning with the insurmountable is a doubled strain, survival Sisyphean: I climbed a mountain and I turned around. I’m older than a few mothers here; older, too, than mothers whose children are forming themselves and leaving newness behind. Even children get older.

There, and here, the youth shrug off disquiet. Attempting ascent while reckoning with the insurmountable is a doubled strain, survival Sisyphean.

Lightning renders the night sky sunset purple, briefly outlining a man holding a starfish pose under the rain. My hands, lightly injured the year before by an electric kettle with exposed wiring, ache in the humidity. I had time to think when it was happening. The current re-inscribed what I shouldn’t have forgotten: that we’re not dying at once. We’re dying discretely, all the time, this life receding as it moves forward, hurrying around feet and challenging rootedness. Once, in a clumsy frustration while moving sublets, I said: I’m not made for this. A stranger overheard and waited until I was facing her: Sweetheart, none of us are. Until then, had I held in mind an image of someone primed for dishevelment and exile?

Read the third essay in this sequence.

1 Samuel Osborne, “Horrific Phone Calls Reveal How Italian Coast Guard Let Dozens of Refugees Drown,” Independent, May 8, 2017.

2 European Commission Legal Notice, “EU Will Support Niger with Assistance of €1 Billion by 2020,” December 13, 2017.