Lather, Rinse, Rewrite: On Translating Eugene Vodolazkin

LITERARY TRANSLATION IS A mysterious form of writing that I love for its mandate: rewrite a Russian book in English so it represents the author’s Russian text. There’s no plotting. No character development. Just the fun of choosing and ordering words as I torment myself over what “represents” means for each book.

LITERARY TRANSLATION IS A mysterious form of writing that I love for its mandate: rewrite a Russian book in English so it represents the author’s Russian text. There’s no plotting. No character development. Just the fun of choosing and ordering words as I torment myself over what “represents” means for each book.

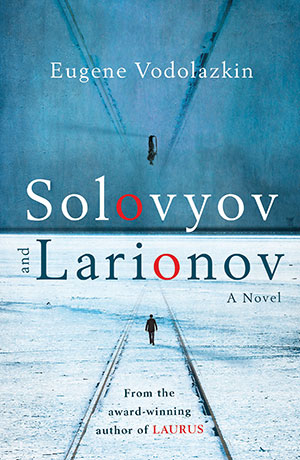

I operate very intuitively and find novels with strong narrative voices particularly appealing; this made the unique textual logic of Eugene Vodolazkin’s Solovyov and Larionov a perfect fit. Vodolazkin’s narrator describes two historical periods that intersect, employing a style that’s almost formal but tempered with plenty of humor. Laughing as I read Solovyov was my first hint that I wanted to translate the book, though I confess to wondering what I’d do with the dozens of footnotes Vodolazkin includes to portray—very successfully, to wonderfully comedic effect—an attribute of academic writing. Solovyov, you see, is a graduate student, and he’s studying Larionov, a civil war general.

Selecting words and phrases is an almost physical process that resembles grasping at shadows. I know there’s a word or phrase in some dark, vacant corner of my consciousness, but as I page through dictionaries and thesauruses—or stare out the window at squirrels—I often get tangled in sticky cobwebs.

Sometimes the search for a word or phrase extends well into the editing process. One of my favorite aspects of Vodolazkin’s books is that he leaves space for the reader’s imagination. As a little boy, General Larionov likes to “traverse the room on his left leg,” imagining he has a wooden leg like his veteran great-grandfather’s. Oneworld’s fantastic editors, whom I love working with—their edits and queries clean up my manuscripts tremendously and save me from all sorts of embarrassing textual blunders—suggested (very understandably) verbs like “hop.” But I wanted a less jumpy word so the reader would create a picture, even a scene, with Larionov. Of course my options got physical at the home office as I agonized over the decision: I imitated the boy, sometimes even hopping, before picking “traverse” to correspond to the Russian verb.

The decision to transform Solovyov’s footnotes was more complex. Vodolazkin told me from the start that I’d likely need to cut them. I adore the footnotes—there’s even an italics-based sight gag playing on two titles—and intended to keep them. But I wasn’t hearing the book properly in the final drafts, something I eventually realized one day in the shower. I’d already excised footnotes with puns and inside jokes that wouldn’t be funny if explained, but by the time I rinsed out the conditioner, I’d decided that transferring the footnote information into the main text would be the best way to convey the novel’s tone in English. I follow my intuition, yet my “trust but verify” practices (which enable me to sleep at night) ordered me to google footnoteless footnotes. Behold the Harvard referencing style! After transplanting citations and commentaries into parentheses and clauses, I’d finally given the English Solovyov a feel that I think represents the Russian Solovyov. Best of all, Vodolazkin—a friend and generous collaborator who reads my manuscripts and even showed me the apartment building in Petersburg where he used to live and where he housed the novel’s Solovyov, too—never said, “I told you so.”

Editorial note: Read the featured review of Solovyov and Larionov from this same issue.