I Can at Least Be a Stumbling Block: A Conversation with Taha Khalil

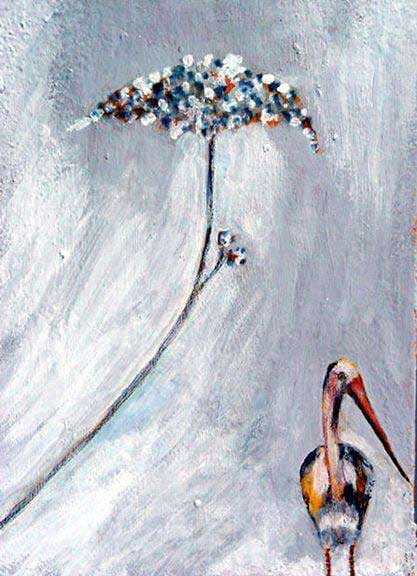

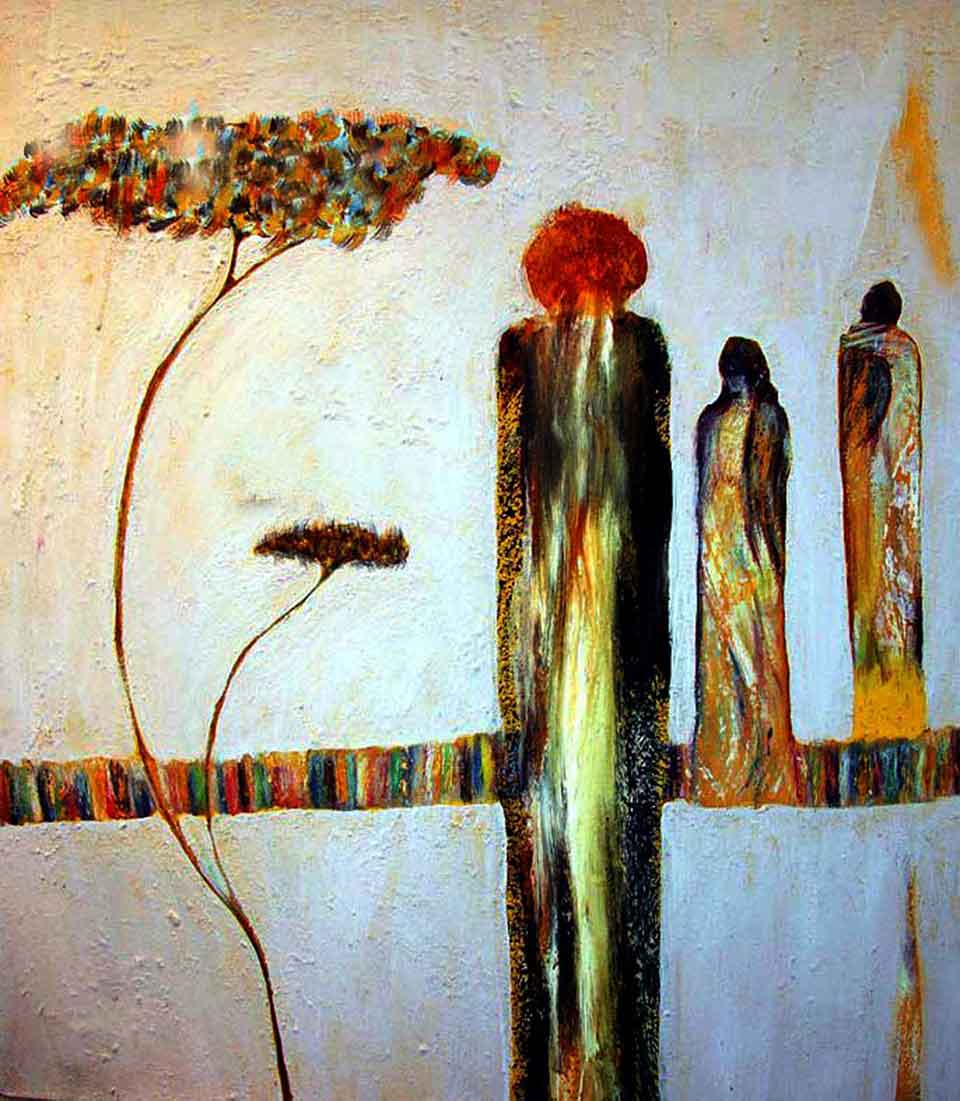

paintings by taha khalil / acrylic on canvas / courtesy of the artist

Over the past several weeks, we corresponded with the multifaceted Rojava writer Taha Khalil, as he worked both in Qamishlo, Rojava, where he continues to reside, and in the Duhok Province of neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan, where he is presently working as the art director for a film directed by his brother, the prominent Kurdish filmmaker Mano Khalil. Zêdan would translate my questions, and Taha would answer via WhatsApp and over the phone. Three of Taha’s poems appear elsewhere in this issue of WLT.

Zêdan Xelef: How would you introduce Taha Khalil?

Taha Khalil: Taha Khalil is like a blue tree fighting for his life in the desert sands, aware of his problematic existence as a Kurd in the region whose people grip axes to cut him down.

David Shook: What is the relationship, in both your work and in your life itself, between Arabic and Kurmanji?

Khalil: I write in both languages. I learned in one of them and grew up with the other one. The relationship between them is spiritual. I can’t avoid either language in life, but in poetry the Kurdish soul overshadows my writing in both of them, while my experience has Arabic features. For me writing in both languages is the only option that feels completely free.

In poetry the Kurdish soul overshadows my writing in both [languages], while my experience has Arabic features.

Shook: What about between the multiple art forms you practice—poetry, painting, your work in film? Are these all part of the same broader vocation or life project, or do you consider them distinct?

Khalil: I paint like poetry, I write poetry as if it’s a scene. Each of them has its own space and time. Poetry is special. Film and painting are striking expressions against oppression and decay, and an attempt to show life’s beauty in the face of war, hatred, and murder against me and my people every day.

Shook: What are you working on now? What are you reading?

Khalil: Right now I’m working on a trilogy of novels—each set in its own realm. Each of the three realms will be an independent book, although they will be connected. I can’t find enough time for painting, but poetry is a significant part of my everyday life—it’s the only thing that makes me feel I can overcome time and aging.

At the same time, I’m trying to document what we are exposed to as Kurds: genocides that are committed against us by the terrorism of the Turkish state and its proxies, the Islamic terrorist groups that hate whatever is beautiful, ethical, and human on earth.

Presently, I’m reading books about Islamic history and culture to understand the current situation here in Rojava, and in order to understand how a president could be proud of his men killing a Kurdish woman on TV, before the eyes of a world gone dumb—and I mean the president of the Turkish entity whose ancestors built their empire across a land that is not theirs, committing massacres against the indigenous peoples of the region: Kurds, Armenians, Greeks, and others. Unfortunately, I’m finding myself compelled to understand this endless war.

Xelef: How do you face the Turkish assault on your homeland, your language, and your culture? How has immigration impacted your writing experience?

Khalil: Without a doubt, immigrating to Europe enriched me. I’m the one who fled Syria, a repressive dictator-state with many lofty values. When I decided to return to Rojava and reside here, I knew that I would be in a constant confrontation with death, and attempts to perpetrate a genocide against our people, both ideologically and physically. So, my choice to reside in Rojava means that I can at least be a stumbling block—even if small—for the tyrants and their crimes that aim to eradicate our culture and our people. Tyrants who do everything to exclude us and uproot us from our land.

When I decided to return to Rojava and reside here, I knew that I would be in a constant confrontation with death, and attempts to perpetrate a genocide against our people, both ideologically and physically.

Xelef: How do you live in war as a poet and artist? What is the biggest impact that living in wartime has on your poetry?

Khalil: In war, the living are bullets’ mistakes. I’m here now only because bullets mistook me; that’s why I always find time to love, write, and make the people around me cling to life against the constant march of death.

In love, a hair falls.

In war, the tyrant falls.

December 2019

Translation from the Arabic