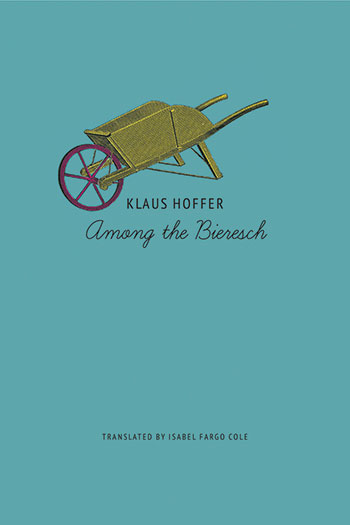

Typhoid (an excerpt)

First published in two parts in 1979 and 1983, Among the Bieresch was praised by critics, winning the Rauris Literature Prize and the Döblin Prize. Forthcoming in English translation from Seagull Books in January 2016, the novel is set in a squalid village on the eastern edge of the “Empire,” a surreal postwar Austria. Young Hans’s uncle has died, and the tradition of his people, the Bieresch, requires him to assume his place for the space of one year. In a series of encounters with the village’s tragicomic characters, their contradictory stories and “scriptures,” the reluctant Hans faces a world both familiar and alien.

During the first phase of my illness, which had broken out so suddenly in the knackerman’s house and then lasted several weeks, it was as though I’d already died.

During the first phase of my illness, which had broken out so suddenly in the knackerman’s house and then lasted several weeks, it was as though I’d already died.

I lay doubled up, legs drawn to my chest, under the duvet, which bulged over me like the crust of a loaf, my right foot shooting out from under it erratically like an animal in ambush. —My eyes ached in their sockets, and I felt that my entire body was covered by a thin sausage skin taut to the point of splitting. Time’s beat was given in silence by my lids, seemingly the only body parts that were subject to my will and still belonged to me. They admitted the image of the bright little window apertures in the dance hall, where my aunt had had my bed moved, believing I would recover more quickly there; and they caught the images that came from within me, and under my lids these images drifted slowly upward over my eyeballs. Both my hands were clenched in firm fists, the thumbs stuck inside them like two little wooden pins.

My mouth was always open a crack. From it flowed a thin, unbroken thread of saliva, which left an unappetizing coating on my teeth and a sort of quickly drying, yellow scab on my cheek, which my aunt wiped away with a moist cloth when she came into the sick room to straighten up my bed. —Part of my life seemed to flow from me with this saliva, but it was a life I no longer cared much about anyhow.

Due to the risk of contagion, I slept separately from her, all alone in the vast, nearly empty room, often lying still on my side to listen to the rushing in my covered left ear and the chirping noise in my open right ear, which projected up stiffly, growing shovel-sized from my head. —The low-pitched rushing indicated the shift in the movements of my blood, as I’d been told, while the high, almost singing chirp signalized the activity of my overstimulated nervous system.

At such moments, mad fear as of a whip’s lash shot through my body and, with a cry meant to end this endless horror, I threw myself weeping from my bed and collapsed with a whimper at its foot.

Sometimes these two noises mingled within me to a kind of noise commentary on the happenings in my body, where in my imagination a gentle soft animal, a quietly peeping mole, burrowed its scratching, rustling way through crumpled paper and crackling wood shavings. And amid this rustle, or so it seemed, incomprehensible sentences and sentence fragments were intoned in Asiatic languages, rapidly shifting between high and low, from one end of my body to the other. —They were snippets of negotiations evidently conducted at incredible speed, and often the parties seemed, in a flash, to have agreed on controversial points and then fallen out again. —Then once more I listened intently to the blowing of my breath, detached from me, sounding like my aunt’s breathing that first night in Zick; as though roused by my listening, it retreated deeper and deeper within me until it lay at last in the very depths, at the bottom of my lungs like a dead thing.

At such moments, mad fear as of a whip’s lash shot through my body and, with a cry meant to end this endless horror, I threw myself weeping from my bed and collapsed with a whimper at its foot.

After each of these cries my aunt almost violently forced open the door of the room—she always seemed quite close by, as though waiting for me to cry out again—looked around, as though there were intruders to drive away, and hoisted me, already quite weak, having lost much of my former weight and now down to barely sixty kilos, in her strong arms to carry me back into bed.

There I lay still, having cast off cares, fear, life and death, and often gazed for hours, thinking of nothing and remembering nothing, at the ceiling of the room, which gleamed down at me white and provoking and on which, through the tears that seeped away beneath my eyelids, the little cracks in the plaster joined of their own accord to form river courses, country roads, and mountain chains, maps of unexplored regions. And on these maps—like a schoolboy faced with a geography test—in my imagination I marked smaller towns with a dot, larger ones with a dot in a circle, and capitals and cities with a gray-shaded field.

I was always delighted when, by way of variety, this sky showed me a new, as-yet-undiscovered section of the world map, and in the sprawling network of arteries I identified a river course I did know, picking up its trail like a clew, unspooling it and following it without difficulties to its end, to its confluence with another, wider river.

And on these maps—like a schoolboy faced with a geography test—in my imagination I marked smaller towns with a dot, larger ones with a dot in a circle, and capitals and cities with a gray-shaded field.

Such imaginative exercises could last an hour or longer. They reminded me of De Selby’s theory of the one-way system; I never managed, not a single time, to follow a river from its confluence back to its source, because I always halted, baffled, at the junctions where the tributaries branched off. —Whereas if I followed it downstream, I rushed along, reeling down the meanders from river bend to river bend, falling from one basin to the next deeper one.

“And so,” I thought sleepily, “one may move from the pool of illness to the pool of sleep, and from this finally to the pool of total dreamlessness, which for you shall one day become the pool of total recovery. —These are exercises,” I said to myself. “You’ll see, they hasten your convalescence, and you’re sure to regain your full health again.”

Turnip

At the beginning of the illness—which the doctor, reachable even in this region that seemed cut off from all natural, vital growth, immediately recognized as a rare combination of special types of nervous fever—my eyes had tolerated only smooth, motionless things. The very wrinkles in my bedclothes had caused me extreme nausea, likewise my hair, which had fallen out in tufts and lay on the pillows like someone else’s rubbish, and once the mere sight of a daddy longlegs sailing up the wall in a draft had made me vomit into the china washbasin by my bed in which my aunt rinsed out the washcloths when she’d cleaned my mouth and face.

Even later on I was completely exhausted at times. My head was too heavy, full of woozy chaos, my limbs ached as though they’d gone through brutal contortions, and above all my hands often trembled at the slightest movement. —Bouts of ague coursed through my seething body and, as on my first visit to the knackerman, my teeth knocked together, clattering helplessly. To relieve these agitations, all I ever wanted was to quickly leave my bed, but barely strong enough to grasp the edge of the mattress, I fell, beaten back by fists, into the rustling cushions, for suddenly cracks appeared all over the dance hall walls as though in an earthquake, sand and lime seemed to sift down upon me from invisible openings in the ceiling, and toilets began to flush of their own accord on floors that didn’t exist.

After about three and a half weeks, I was more or less—“halfway,” as the unsuspecting doctor put it—recovered, but the very mention of this name set me back another ten days. The skin of my face tautened again and my body was distended by intestinal gases.—At last, however, I was allowed my first meal, albeit only thin soup and porridge, and sometimes my aunt—her behavior toward me had changed fundamentally since the night of my naming, now overly solicitous—brought me a little lukewarm brandy in a cup. “To strengthen your poor, weakened heart, and make you better again quite soon.”—Later I was allowed to sit up by myself for the first time (not counting the involuntary, but unavoidable, horrified leaps out of bed) and also received permission to read three books my uncle had left behind.

One of these books was a ten-year-old illustrated catalog for stamp collectors; the second was on horticulture, proclaimed by the dust jacket as Collin’s famous work Planting the Best French Fruit Trees: A Thorough Guide; the third bore the title Almanac for the German Family, and below it Vade Mecum for Young Ladies. —Once again I found the former owners’ names in long rows on the inside covers, once again all the names, down to the last, that of my uncle, were crossed out, and I felt confirmed in my fear that these books, too, were moveable goods that could be stolen from my bedside at night along with my washbasin and my nightstand.

An enthusiastic reader, I soon finished the books and read them a second time. I searched the stamp catalog for depictions of young African nations’ sacred heraldic animals and pictures of strange tropical birds, as I’d always been interested in zoology and had planned to become a naturalist someday. Collin’s book interested me mainly for the section on the grafting and pruning of espalier fruit, which contained a history of fruit tree grafting in ancient Mesopotamia, the Persian Empire, and among the Egyptians, sophisticated cultures that had all held to the notion that trees had inherent sex-specific characteristics which predisposed them for the grafting of certain scions, while the fixed sex role precluded the grafting of other ones from the outset, unless such an “unnatural transplantation of incompatible and hostile races of wood” was desired for the manufacture of divining rods and other magical instruments.[1]

And over and over I leafed through the Almanac, in which alongside recipes and housekeeping and child care instructions I found the symptoms of typhoid, my affliction, presented in detail.

“He’s been struck by the hoof of a mule,” they say here when someone raves with fever. —This illness had dealt me a deep, gaping wound, and in the beginning I often felt I had a small hole in my chest through which the air escaped as through a side exit. The wound fever still racked me, but gradually a scab was forming around and over this opening. It was a great star-shaped medal conferred on me to cover the scar that would remain. —Filled with pride, I wanted to show this decoration to all and sundry—“Here, look here, my Cross of Valour, the bar, the ribbon!”—above all to Turnip, my little dog, whom my aunt, after consulting the doctor, had reluctantly admitted to me in the dance hall.

I also read to the dog at random from my three books. —She lay blinking, her short legs stretched out in front of her, on several tattered floor-cloths which my aunt had spread out for her by the door across from me. —When I looked at the animal, lying there and gazing up at me mutely, I had the strange feeling that the first two days of my stay in Zick had, so to speak, become flesh in her; that she was a living memorial to my self, or an early stage of it turned memorial, which I had forced out from me as though giving birth and which, perhaps quite soon, would take my entire illness upon itself; indeed, that it would bear in my place what had been ordained for me. —Egynek—egyeb, I said to her. This, as I had learned, was the refrain of a counting rhyme, meaning “one for the other.”

“One person’s illness,” I read to this body that was a piece of myself, “has a harmful effect on the other, adding to his work, taking away his joy in life, bringing care and sorrow to the house.”[2] —Regarding the word “typhoid,” I learned from the Almanac that it means “smoke,” “haze,” “stupor,” perhaps even “stupidity,” and that it belonged to the same family of words as “dust,” “dull,” “dark,” and “dumb.”

“At one time it was generally known as nerve fever,” I said out loud to my dog. “This is the term for various severe medical conditions associated with high fever, in which the nervous system persists in a prolonged state of torpidity. —The intensity of the fever, which poses the greatest risk at the outset of the illness, is combated with full baths cooled by pouring in cold water at the foot end while the invalid sits in the tub. Apart from lowering the fever, these baths achieve bodily cleansing and overall stimulation, especially with insensible patients. This transforms severe cases of typhoid into simple ones and reduces mortality to a minimum. —To avoid the risk of intestinal laceration, the patient is initially given only liquid or semiliquid nourishment, and that in small portions. Though the symptoms are life threatening at first, the illness often ends with the patient’s recovery. As for the treatment of typhoid, the patient must first be quarantined. The sick room must be large and frequently and thoroughly ventilated. The mouth must be cleansed regularly with a damp linen rag.”

“Typhoid,” I read on, giving Turnip a warning look, “is an extraordinarily contagious disease. The contagion is contained in the air and in insufficiently ventilated rooms can persist for a long time without losing its effect.”

Translation from the German

By Isabel Fargo Cole

Editorial note: From Klaus Hoffer, Among the Bieresch, part 2, chapter 1. Read Cole’s note about translating Among the Bieresch in the January 2016 issue of WLT.