A Second Reunion

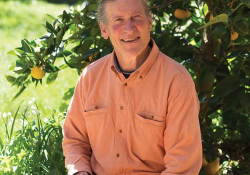

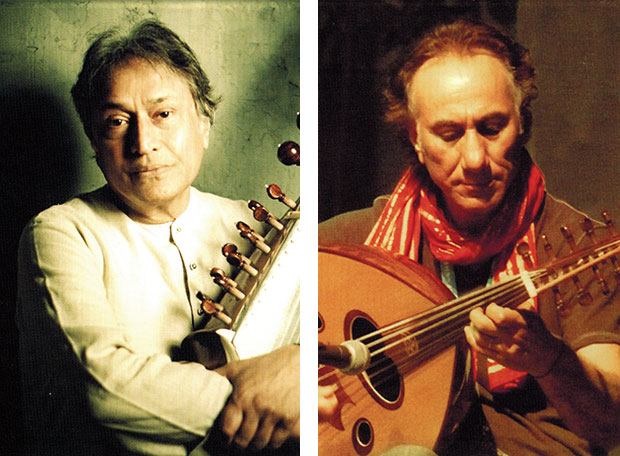

The sarod is an instrument used in North Indian classical music whose origin is shrouded in mystery and no small amount of controversy. What is not in dispute is Amjad Ali Khan’s status as a living master of the instrument and Infinite Hope (2015), his second collaboration with Iraqi-born oud player Rahim AlHaj, as extending upon the Grammy-nominated successes of their first outing, 2009’s Ancient Sounds.

Infinite Hope’ s compositions, seven in total and adding up to more than an hour of new music, are simultaneously rooted in the traditional and the contemporary. The instrumentation, featuring sarod, oud, a variety of percussion instruments, and the occasional voice accompaniment, exudes a classical Indian soundscape—sinuous lines unspooling over deceptively complex accompaniments that add and subtract layers in response to subtle rhythmic shifts in the melodies.

Despite this clear nod to the core traditions of Indian classical music, AlHaj contributes to Infinite Hope as both performer and composer in ways that might not be evident upon an initial cursory listen. Both Indian and Arab classical music is often composed through a structured improvisation wherein the composer explores a predetermined set of melodic material, resulting in a piece known in the Indian tradition as the raga and in the Arab tradition as a taqsim. These compositions can easily stretch on for thirty minutes or more and, unless the listener is knowledgeable about the conventions of the forms, can seem to meander without purpose.

AlHaj, a 2015 NEA National Heritage Fellow, has taken a different approach in his recorded output—creating pieces with more obviously structured melodies that leave a door open for uninitiated listeners to appreciate the melodic and rhythmic specificities of Arab music. On Infinite Hope, he exerts this compositional influence afterthe fact, taking recordings made by Khan (as well as his sons Amaan and Ayaan, who contribute on four tracks) and reorganizing them around strong central melodies while adding his oud parts in response to the composed final product. While the method may horrify purists, the result is anything but inauthentic. AlHaj is a sensitive curator of these melodies and brings a compositional focus to the songs—some of which still stretch into the twelve-minute territory—that is often difficult to produce from a pure improvisational recording.

Some musicologists believe that the sarod is an Indian variant of a Central Asian adaptation of the ancient oud. As such, these collaborations between AlHaj and the Khan family may represent the first reunion of the popular Hindustani instrument with its musical forebear. There is an unmistakable beauty in the juxtaposition of the sarod’s fat, quicksilver tones against the more percussive oud lines, which dance deftly around them, that would have remained unheard without this compositional process. Whatever traditional conventions that had to be sacrificed in order to realize this sweet homecoming must surely be acknowledged as being for the greater good.