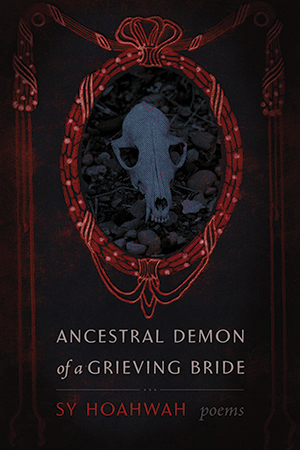

Ancestral Demon of a Grieving Bride by Sy Hoahwah

Albuquerque. University of New Mexico Press. 2021. 64 pages.

Albuquerque. University of New Mexico Press. 2021. 64 pages.

TO ENTER SY HOAHWAH’S Ancestral Demon of a Grieving Bride is to immerse yourself in liminality and enter the poet’s world of monsters and medicine (see WLT, May 2017, 53). Portal imagery recurs throughout the book: doorways, a window through which the speaker escapes from “the sunset’s Luciferan face,” and a “blood trail” leading to the sky that opens to the “next world.” This world and the next are separated only by a “[l]ine of barbed wire.”

The collection’s imaginary is a crowded reliquary: a severed yet animate finger writes “love letters to the rest of the hand.” Skulls are repurposed as lanterns for the dead, and a decapitated head sings. There is more life in the dead than there is in the living. However, mapping the collection’s oppositional imagery reveals that the contest for the speaker’s “trashbag” soul is “neck to neck”: “Shadow vs. Light Black Hat vs. White Hat.” Medicine offers healing while its dark twin, sorcery, threatens to consume the seeker. Light battles against the darkness of death, vampires, and demons. Time and space are subject to compression that is not based on technological innovation but instead upon a vertical dimension that instantiates the past, present, and future into place. The wagon of Time changes places with the mule of Eternity.

In “Hell’s Acre,” the final five-part poem of the book, the speaker’s Virgil is a skeleton who guides him through the “Hinterlands,” where the speaker’s Native ancestors lived “beside the fort / that’s neither on the maps of heaven / nor of hell.” Throughout the collection, as in “Hell’s Acre,” Hoahwah’s layered poetics and metaphorical tapestries leave the reader unsettled by a series of paradoxes that create epistemic vertigo. However, there are hints that balance can be found in the alchemy of poetry, medicine, and ceremony. Combined, they might transmute historical genocide into an answer to Zen master Ikkyu’s koan, posed in Hoahwah’s collection by his skeleton-guide: “When are we not in a dream? / When are we not skeletons?”

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

Oklahoma City University