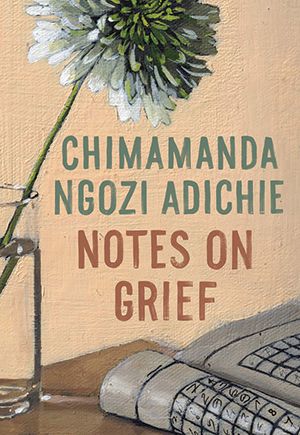

Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2021. 80 pages.

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2021. 80 pages.

NOTES ON GRIEF is two portraits in one: that of a loved and loving man, and that of a daughter undone by grief. In a series of diary-like entries, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie tenderly and ragingly writes about her father, James Nwoye Adichie, who died unexpectedly in the summer of 2020. The cause, Adichie tells us, was “complications from kidney failure,” but given the times, she “wonder[s] about the coronavirus, of course.” She is in the United States (where she lives and works) when she gets the news. Nigerian airports will stay shut for another few months. She is inconsolable. Her Zoom call with her family “is beyond surreal, all of [them] weeping and weeping in different parts of the world, looking at the father [they] adore now lying still on a hospital bed.”

Initially published as an essay in the New Yorker under its “personal history” rubric, Notes on Grief, however, reads like a mourning handbook meant for our pandemic-ravaged world. Opting for a less tinselly style than she has previously gone for, Adichie surrenders to the crassness of use that serious writing is meant to eschew, proliferating line after line on the nature of grief that are wittingly wise, comforting, and insightful. “Grief is a cruel kind of education,” Adichie writes. “You learn how ungentle mourning can be, how full of rage.” The condolences of relatives rankle her; “needle-pricks of resentment flood through [her] at the thought of people who are more than eighty-eight years old, older than [her] father and alive and well”; and the sight of well-wishers “bending to write in the [condolence] book” at the funeral causes her to have a mental fit. “Go home!” she thinks. “Why are you coming to our home to write in that alien notebook? How dare you make this thing true?” But though grief wholly consumes Adichie’s body and mind in the days following her father’s death, turning her pugnacious, uncharitable, and resentful, it also brings her to reflect deeply on our humanity.

Language—“the failure of language, and the grasping for language”—is a key preoccupation in the book. Adichie reminds us that we are fundamentally linguistic beings; how our lives are constituted, unraveled, and sustained within the terms of language. She fondly recollects the names she used to call her father, and those he gave her in turn, his hailing “a love-drenched litany of affirmation.” She tells us the Igbo word for “sorry,” ndo, brings her some degree of comfort, as do the many kindly adjectives those who knew her father use to describe him. She highlights those expressions commonly conveyed to the bereaved that have “a taint of the inapt”: “on the demise of your father,” “he is resting,” “he is in a better place.” She reconsiders her own words relayed to grieving friends in the past, noting their banality: “‘Find peace in your memories,’ I used to say. To have love snatched from you, especially unexpectedly, and then be told to turn to memories. Rather than succor, my memories bring eloquent stabs of pain that say, ‘This is what you will never again have.’” She laments how she will “no longer see the square with the word ‘Dad’” on her phone and admits how it was difficult for her to write the word “funeral” when messaging relatives. For the funeral, she gets T-shirts made with words that memorialize her father: “On some, I put his initials, ‘JNA,’ and on others, the Igbo words ‘omekannia’ and ‘oyilinnia’—which are similar in meaning, both a version of ‘her father’s daughter,’ but more exultant, more pride-struck.”

At less than a hundred pages, Notes on Grief may seem like a slim offering, but in its raw, honest, intelligent, and indelible representation of what the process of grieving a parent looks like, it is a robust addition to Adichie’s oeuvre.

Yagnishsing Dawoor

University of Oxford