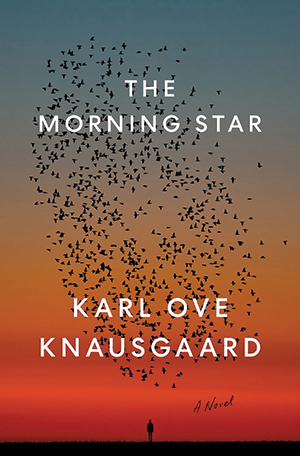

The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgaard

New York. Penguin. 2021. 666 pages.

New York. Penguin. 2021. 666 pages.

“FIRSTLY THERE WAS no plot, and secondly there was no sequence of events, and no coherence, everything came at you higgledy-piggledy.” So Karl Ove Knausgaard describes in the fifth volume of My Struggle some of his painstaking efforts to complete his first novel, 1998’s Out of the World. After publishing another novel six years later and then abandoning the form altogether, one can sense in these words Knausgaard’s discomfort with the demands of fiction: plot, character development, readers’ expectations. His response to such constraints was ultimately made manifest in the completion of his massive autobiographical My Struggle series. Since that project’s completion, Knausgaard has written a series of similarly autobiographical books loosely related to the four seasons, collaborated with Fredrik Ekelund to document the 2014 World Cup, and published a remarkable piece of criticism on the work and life of Edvard Munch. These efforts have been marked by an approach largely similar to the one seen in My Struggle: intense self-scrutiny, crystalline imagery, and a proclivity for the spontaneous.

The Morning Star, Knausgaard’s long-awaited return to fiction, finds the author operating in a familiar thematic vein by exploring notions of family life, the boundary of death, and the nature of belief and reality, while doing so in a wholly new context: the end of the world. A new star suddenly appears in the Norwegian sky, heralding strange visions, the dead returning to life, and the arrival of an ominous winged creature. These strange events are experienced not by the singular narrator of Knausgaard’s autofiction but instead by a small collection of narrators, which allows Knausgaard to portray how a singular world-changing event can draw out varying shades of human drama, for despite the apocalyptic focus of the novel (which runs a seemingly purposeful 666 pages), its primary concern is what an apocalypse reveals about the inner lives of its characters. Kathrine, a priest, is frightened by the continued reappearance of a man whose funeral she has recently performed; however, it is her realization that she may no longer love her husband, and her response to that realization, that truly haunts her. Likewise, it is Turid who has perhaps the closest encounter with this strange creature, but foremost on her mind throughout the nightmarish events she endures is the well-being of her depressed son. Martin Aitken’s translation retains the evocative language of his earlier contributions that were characterized by starkly beautiful descriptions of nature and the warm realism of domestic life.

Throughout The Morning Star, Knausgaard rarely loses sight of the mundane and the personal amidst all the biblical-scale upheaval. One character certainly runs counter to this. Portrayed as both a scholar and a dilettante, Egil is a difficult character to read on account of the considerable number of pages allotted to his story. Is he meant to be taken seriously or is Knausgaard poking fun at himself? It can be hard to know at points. It is his lengthy essay on death that concludes the novel and bears the marks of Knausgaard at his most heady and unrestrained, recalling especially the last volume of My Struggle wherein Knausgaard shifts from his spare, naturalistic, and disciplined persona into the dry and garrulous academic devoting hundreds of pages to an analysis of Paul Celan’s poetry and the life of Adolf Hitler.

It made for difficult reading then as Egil’s pages do now, tucked in as they are among characters that not only have far more at stake but are also enlivened by their more proximal exposure to the events of the apocalypse. It is only when Egil turns to his own life and recalls the events of one strange train journey, the most direct and powerful passage in the entire novel, that his value as narrator begins to reveal itself and you understand why Knausgaard chose his voice to be the concluding one of this book, the first of a planned series that should put both the author and his audience at ease regarding his facility with the demands of fiction.

Phillip Garland

St. Louis, Missouri