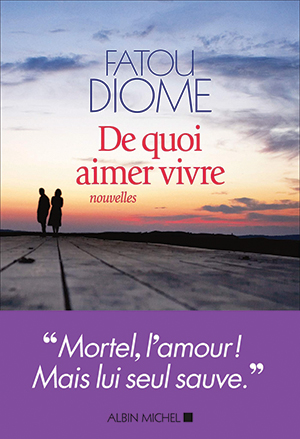

De quoi aimer vivre by Fatou Diome

Paris. Editions Albin Michel. 2021. 240 pages.

Paris. Editions Albin Michel. 2021. 240 pages.

“AH, LOOK AT all the lonely people!” The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” refrain captures the essence of Senegalese writer Fatou Diome’s 2021 short-story collection De quoi aimer vivre (Enough to make us love life). It is peppered with characters on the edge of society, longing for human connection and fulfillment. Their lonely exclusion is frequently explained through their remembered pasts, while the book’s title unites the stories’ characters: we must all have something that makes us want to live. Bread alone is not enough.

Disabled Andy, D. D. the washed-up boxer, divorced Octave, refugee Samira, the poor Senegalese fishing family: all frequent the typically Diomien liminal or marginal spaces, such as the café, the empty apartment, the mountain cabin, and the coastal fringe. Varying her trademark focus on the Black woman migrant, Diome still pursues her key themes of the quest for personal fulfillment and social integration. All but two of the stories are set in Europe, the exceptions returning us to Senegal with “La Marmite du Pêcheur” (The fisherman’s stewpot) and to the beloved navigator grandfather, represented here by “Le Vieil Homme sur la Barque” (The old man on the boat), a 2010 story.

The two opening pieces stamp the collection’s identity. “Une Fenêtre pour les Anges I – Présence, II – Absence” (A window for angels: I – presence, II – absence) richly configure the fragile relationship between Andy, a disabled white French man and the Black Senegalese woman narrator, charting the ultimately successful achievement of unconventional friendship while illuminating Andy’s experiences of disability as he counters others’ repulsion with resilience and forgiveness.

“Le Bleu de la Roya” (Roya’s blue) and “Le Vieil Homme sur la Barque” explore the figure of the man-savior: the Italian shepherd shelters the Libyan refugee, and the fisher-grandfather guides the little Senegalese girl—in the present and in memory. A welcome reprint of a 2002 story, “Ports de Folie” (Ports of madness), traces a woman’s obsessive dramatization of places where her absent lover is traveling. “Indémodable!” (Timeless), whose talking dress recalls the speaking objects of Diome’s novel Kétala, also enacts the longing for the absent beloved.

De quoi aimer vivre reminds us of the strengths of Diome’s earliest work, the 1990 short-story collection La Préférence Nationale (National preference). This 2021 volume illustrates how the novelist flourishes within the story genre’s tighter formal framework.

Rosemary Haskell

Elon University