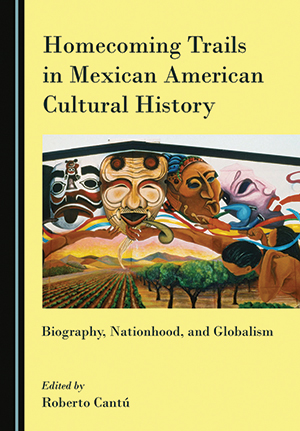

Homecoming Trails in Mexican American Cultural History: Biography, Nationhood, and Globalism

Newcastle upon Tyne. Cambridge Scholars. 2021. 206 pages.

Newcastle upon Tyne. Cambridge Scholars. 2021. 206 pages.

ROBERTO CANTÚ’S Homecoming Trails in Mexican American Cultural History is a welcome contribution for understanding the times we live in. The collection of essays explores perspectives on the Americas grounded in biography, nationhood, and globalism. Coming out of a 2018 fiftieth-anniversary observance of the founding of Chicano Studies at Cal State LA, this book asks what it means to be American, especially Mexican American, not the platitudes of citizenship but the historical conundrums that shape nationhood and identity. You might ask how the founding of Chicano Studies helps accomplish that. This book sets about answering that question from several key vantage points.

Cantú and his contributors want to understand the historical development of culture in this hemisphere, free from prior commitments to deconstructive apparatus or the exclusive terms of race, gender, and class. The book doesn’t avoid these perspectives, but it resists being captured by any of them. One can think of Chicano Studies during the theory era of the 1970s and beyond and studies of the literature and culture that told us more about structuralism and deconstruction but precious little about Chicano literature and culture. The result is a series of essays that reexamine Mexican American cultural history free of theoretical jargon.

Mario T. García, for instance, starts his essay by saying that “my family roots bridge important aspects of Chicano history,” immediately setting the personal and yet critical tone that will characterize his essay. He assesses challenges to American democracy in the Trump era but reasserts the overarching indigenous perspective and the likelihood that “we will prevail.” Likewise, David Montejano, in “On Memory and the Writing of History,” zeroes in on “how my life experience has influenced my research and writing.” In “Wind, Water, and Wasteland,” María Herrera-Sobek wants her readers to understand “the quest for social justice and [the need for] action.” This coupling of knowledge, scholarship, and the need for action is an indigenous move that completely undercuts the Western habit of presenting knowledge as divorced from action or practical purpose.

There is a name for this kind of writing that most of us have forgotten: the essay. It is a form that is critical and measured in the case it makes, and yet it is intensely personal, so we are always aware that human beings are dealing with the consequences of what happens in history. In a word, the contributions to this volume are implicitly making the case that critical commentary needs to move back to assessing the impact of culture and history on people. These are exactly the assumptions that come with writing the critical essay, and this book is one big argument for that critical and personal recovery.

The case for the return to the essay in literary and cultural studies is made most clearly in Cantú’s own writing. A master framer of arguments and scholarly apparatus, Cantú also gracefully recounts the work he did to create this volume, appeasing his “younger Chicanx and Latinx colleagues” with subtitles and concessions related to current critical trends. He keeps his eye on the need to inform people about their historical foundations and to improve the quality of people’s lives through knowledge about the past. We are aware all through this volume that Cantú’s guiding hand is keeping its contributions on track to serve the interests of real people. In effect, Cantú is our inside guy, a scholarly practitioner who is committed to the critical and yet personal commentary that is characteristic of the critical essay as opposed to the scholarly article. Homecoming Trails in Mexican American Cultural History is that rare case of high-level scholarship trying to get around the shortcomings of the academy by writing as if real people are reading.

Robert Con Davis-Undiano

University of Oklahoma