Worlds Within, Apart

In this lyrical essay, a son looks back at the hamperings of language and the distances left in its wake.

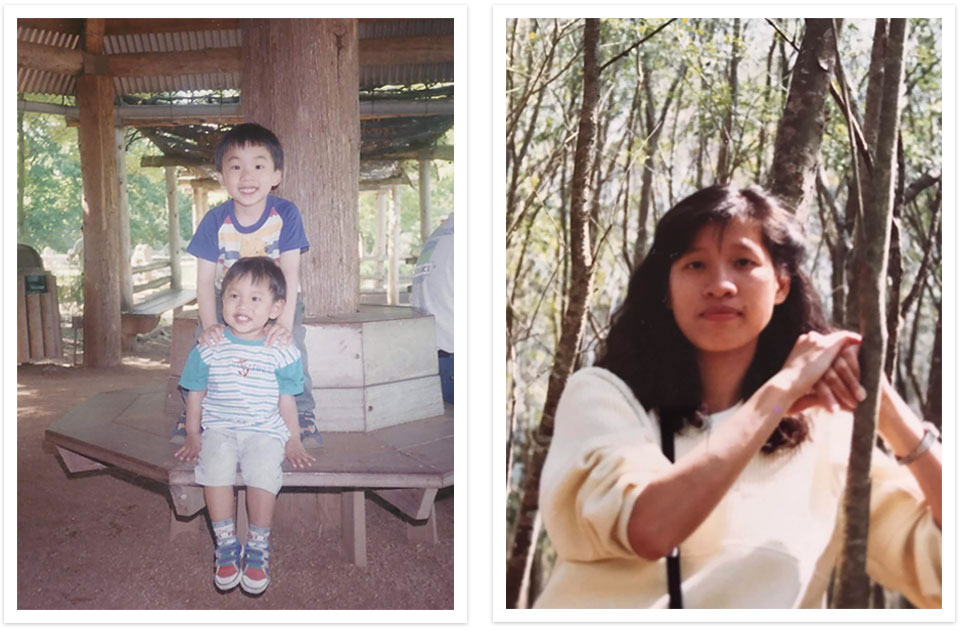

Eliot and I used to giggle in the back of our seven-seater minivan whenever Ba would shift around in his seat. Eliot would peek at me from behind his oversized winter coat and whisper, “I think Baba just farted,” and I would sniff the air before scrunching my nose in agreement.

“What are you boys talking about?” you would ask. “What’s so funny to you two?”

“Nothing, Mama,” we’d respond, and laugh harder still because we were Navajo Code Talkers embedded in our own family. We knew a means of secrecy more effective than Pig Latin.

We learned early on the power of this obfuscation. I would tell you in Mandarin that we were going to the park five minutes away from our house, and then before you even left, turn to Eliot and detail in English our plans of biking across the four-lane road that you forbade us from ever crossing. I could calmly tell Eliot to suck a dick in front of you, and for all you knew, we were talking about a type of candy. I could tell him to eat shit or to stop being stupid as we walked to the park and you wouldn’t even break stride.

It became a way for Eliot and I to construct a world invisible to your eyes. At first, this world contained a few innocuous misdeeds and bad words, maybe an Arthur episode you didn’t understand or a school enrollment form you couldn’t decipher. But as we grew older, its appetite grew insatiable, its reach gradually engulfing friends, concerned teachers, the Dominick’s cashier who wouldn’t take your coupons, people who ignored you, people whom you shouted at for ignoring you.

It soon became clear that it was you who occupied your own world, one equally as invisible.

♦

THERE WAS THE TIME we brought our car into Firestone, when our car had trouble starting and you thought it was an issue with the battery. When the mechanic came out with a laundry list of action items and a bill totaling over five hundred dollars, you were livid. You harpooned a barrage of emotionally charged half-English, at times pounding your fist in the frustrating absence of words.

It soon became clear that it was you who occupied your own world, one equally as invisible.

“I want [to] see [your] manager [right now because this is fucking absurd that] you charge[d] [me] five hundred [dollars for a] battery [replacement when it is advertised in this ad as one hundred dollars. Do you think I don’t know that you’re adding arbitrary line items? You’re telling me that] I [need to replace all these things that I had already] replace[d] five months [ago]?”

I kept my gaze squarely on the Sports Illustrated magazine in my hands. Surely, if I kept my head down long enough, people would confuse me for the adopted son of one of the other customers, the ones who at this point were all trying to pretend like nothing out of the ordinary was happening.

But I didn’t need to look up to feel your gaze, your cue for me to step in and articulate your anger for you. I didn’t want to. I just wanted to stay invisible.

♦

“SO WHAT IF THEY have a GameCube? We have things to do here too,” you would say. “I can even cut up some fruit, plate it nice with the orange slices around the apples.”

But it wasn’t about the GameCube, or the barbecue chips, or even the chilled juice boxes that sat in their basement minifridges. It was about a certain desire to keep my worlds apart: the world that I had constructed for myself—the one that I would tell at school—and a different reality that sat within our walls.

I didn’t want them to prod at the oddities at home. I didn’t want them to probe the lamps held together by globs of gray putty or the twisty ties threaded through as makeshift oven handles. I didn’t want them to ask which channel Disney Channel was on, that we had cable only during the holidays when they ran promotional rates, or tell them to sit only in the safe chairs and not in the ones haphazardly strewn together with staples, super glue, and a relentless determination.

It was about a certain desire to keep my worlds apart: the world that I had constructed for myself—the one that I would tell at school—and a different reality that sat within our walls.

But in reality the discovery I feared most at the time was you.

That you would emerge out of the kitchen with bowls of adzuki bean soup and greet my friends with incoherent salutations, your presence and goodwill somehow anomalies that I had to explain away, to apologize for.

Oh, sorry, she doesn’t speak much English.

She’s asking what you want to eat—sorry.

Actually, do you want to just bike around outside?

Then, over time, you adjusted to accommodate this unspoken narrative that I had constructed. Whenever the doorbell rang, as if on cue, you would quietly make your way upstairs and slink away into your room. Before you shut the door, you would relay to me the next two hours’ worth of information knowing you wouldn’t see me while people were over. Or perhaps more accurately, that I didn’t want them to see you.

In public, you began apologizing for yourself before I had a chance to. You began saying less and letting me interpret more, filling the gaps of conversations with overwrought laughter. You retreated further into your world, and I into mine.

♦

PEOPLE CLOSE TO ME know you intimately through the stories that I tell, the same stories that you tell me not to tell but that I tell anyway. How are people to understand my reflexive fear of leaving pants on the floor if they don’t know about the penis-gnawing spiders of your lore? How do I explain accidentally referring to a friend as “Harry Potter” without betraying the fact that you refer to all my friends by (often wholly unfounded) resemblances to movie characters? That you do so because “how am I expected to say a name like Jay-nee-fur?”

Mama stories are what Eliot and I call them. Loosely defined, these are tales from our childhood that usually involve you (Mama) spouting some bombastic claim rooted in your ever-fluctuating opinions, often citing sources such as “an article I read in Chinese that you wouldn’t be able to understand anyway” or an all-too-convenient (and relentlessly unfortunate) friend of a friend of a friend.

I tell people how, for you, recipes are but loose guidelines, that through a series of substitutions you deemed appropriate a shrimp scampi recipe could produce a dish of leftover salmon, marinara, and udon. Or how when we complained about never celebrating Thanksgiving, you drove out and came home that night with a Boston Market turkey paired with a full set of Wendy’s chicken nuggets, presenting it as an equal substitute to the feasts we saw on ABC Family.

And of course, there was the time when I was eight or nine, when the living room curtains were so jammed that we just left them closed and kept the living room perpetually dim. It started out as a “we will fix that,” but years passed and it became a “there are probably higher priority issues,” until one day you woke up and suddenly declared it the most pressing problem in our family. Ba, the trained physicist that he is, started carefully and repeatedly measuring out the dimensions of our curtains before drawing a myriad of to-scale diagrams. He researched different brands across five or six different websites to make sure the curtains we bought would have proper warranties, that they had the highest reviews online, and that if they didn’t, figure out why.

During this ordeal, you became increasingly frustrated with what you perceived to be an overcomplication of a simple problem, so while Ba was at work and Eliot and I were at school, you decided, as you’re wont to do, to implement your own solution.

I still cannot describe the reaction that Ba had when he came home that day.

Two emblazoned American flags hung side by side where our jammed curtains once were, sunlight faintly bleeding through from behind the sheer butcher-paper material. The bottoms of the flags were trimmed off just a tad short so light peeked in from beneath as well. Eliot, then six, thought it was an act of incredible ingenuity. I didn’t know how to react.

You, of course, stood in front of your creation and proudly announced that you had found them on clearance in the back of a Menard’s (“Seven dollars each and nobody’s buying them? What a waste!”) and immediately made the connection that they could be used as curtains (“Isn’t your mama too clever?”). You then assured us that these curtains would only be temporary (they remained up until we moved out six years later).

Ba followed with a barrage of questions and concerns ranging from how flags aren’t meant for this purpose, that this might be seen as disrespectful, that the flags were too sheer, and so on, and in response you defiantly grabbed the bottom of the flag and rolled it up to reveal the assorted patches of yellowed and dying grass in our backyard.

“It works, doesn’t it?” you said, laughing. “I think roughly is good enough.”

♦

IN ANOTHER WORLD, we sit around the dining table: Ba and Eliot at one end, you and me at the other. Next to me is my friend whom you suspect stands on his toes to make himself look taller in photos, or perhaps it’s the coworker from Barcelona whom you think is “almost certainly related to Bill Gates.” Maybe it’s my wife, the one you go on walks with and whose mannerisms you tease, and we have two kids, too.

Whoever it is, they see everybody’s favorite aunt, the one who’s always bringing back to Taiwan an eclectic assortment of American candies, the one who will sit and argue with our five-year-old cousin when everybody else has grown tired. They see the impassioned Chinese schoolteacher who stays up late on Saturday nights brainstorming educational games even though the other volunteer teachers just reuse the same flash cards from years past.

They see a woman who stands by her resolve, who is frank without regard for etiquette, who takes matters into her own hands, who is foolishly confident and wildly creative. They see a woman as unshakeable as she is vulnerable; thoughtful, short-sighted.

Your mom is just like you described her, they say, and in that world, I rejoice. A burden snaps as the divide between my two worlds bridges and the gap closes. I can’t believe I never met her before.

But in this world, you sling your arms around my girlfriend’s waist, substituting touch for absent words. I watch from afar (I wait in the car because you tell me to) as the two of you walk into the Korean bakery. You enthusiastically point out different cakes and pastries that you think are good and she nods, smiling politely. I see you laugh loudly (I can’t hear, but I see your teeth and your heaving shoulders). She continues smiling.

I bring to you my writings, but all I can do is translate to you an approximation.

I imagine you pointing at a sponge cake and telling her how we once tried to make them because you loudly proclaimed, “I paid seven dollars for this? I can bake cake better than this!” The cake came out as bread and you tell her we should try to make them again. Or you might tell her how Ba used to bring pineapple cakes back from Taiwan whenever he traveled back for his research, how eagerly Eliot and I awaited them. Maybe you tell her about how matcha cake is your favorite pastry because you think American cake is too sweet for you. You espouse sweeping generalizations about the American diet based on anecdotal experience and warn her to “watch out for American sugars.”

I don’t know what you tell her, but all she does is continue smiling. As you turn away, I see her enthusiastically bring something up, but now it’s your turn to smile. Laughter and smiles grow increasingly contrived until she wanders off into one aisle and you into the other.

Attempt upon attempt to reach you falter, giving way to an impassable quiet. Eventually, you always wander back up the stairs to your room, to a world where silence is the better alternative. But even that world, that shielded microcosm where we once shared secrets and exchanged stories, is no longer what it once was. I find myself bringing to you more and more foreign artifacts, artifacts that I have to interpret and describe. I bring to you my writings, but all I can do is translate to you an approximation. I tell you about my new friends in college, but I know their essence can exist only through my descriptions and stories, and that your essence exists similarly for them. In many ways, the hamperings of language have begun to bleed into our relationship, and I don’t know how to stop its relentless plow.

In our world, we now share a language of approximations, inaccuracy and vagueness our conduit. Whereas it once pained me that I couldn’t share you with others, it now pains me more that I cannot share even parts of myself with you.

♦

YOU WON'T SEE this letter. I won’t share it with you.

I know you will make your best attempt to read it, that you will sit on our puke-green corduroy couch with your silver clamshell translator beside you and inspect my sentences line by line, word for word. You will ultimately resign and call me, ask that I give you a da gang. You will ask for a summary because da gai jiu hao le.

“Come on, just give me roughly what it’s about. What’s the main takeaway?”

And what do I tell you then? That roughly isn’t enough? That you can eyeball two teaspoons of butter, or curtains in a living room, but you can’t approximate lives and feelings? That I’m afraid if you could understand this letter, you would tell me a truth that I don’t want to hear?

That, perhaps, this language of approximations is all that we can share?

Stanford, California