The Year of Jazz

This essay takes the form of a jazz standard. Nestled within the intro and outro are alternating A and B sections. I am sustained by John Coltrane’s music and the company of a dog named Jazz, as I liken the experience of lockdown to that of a bizarrely acquired concussion.

Intro

The alpha puppy, I learn later, is untrainable. Determined. Feisty. Smart. Bossy. Mischievous. An improviser. Will not fetch. The dog trainer gave her back after a week of residential training. He never cashed my check.

My daughter and I named her Jazz. Life is complex. The child says, Jazz, short for Jasmine. I say, the puppy’s name was Coltrane’s fault as she was to become one of My Favorite Things. His version of the eternal tune. Precious and unfathomable.

A

When the tent pole first went up my nose, it shook up my brain and me so much that it took a bit of a break and went off to Bermuda or was it Brazil. I had not traveled to Brazil yet at that time, so it must have been Bermuda. A place that I’ve never been drawn to and never wished to go.

I pulled the tent pole from my left nostril. Blood gushed out onto the sands of Sunnyside Beach. I turned quickly away from my daughter and the other children, so that they would not see. My friend, Jacqueline, gathered them and pulled them far away. I moved northish. A stranger sat me down on a bench. She called an ambulance. The attendants asked a few questions. They smothered laughs. A tent pole up the nose? An ambulance for a nosebleed? It was a two-minute drive to St. Joseph’s Hospital.

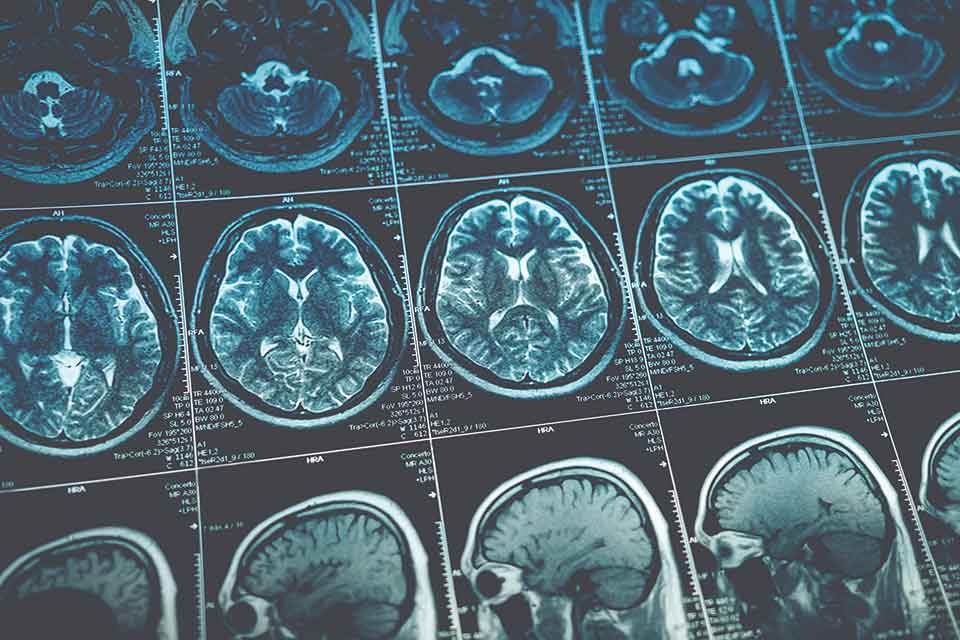

An emergency room doctor said, “Take a couple of days off of work” and wrote a note to that effect. On day 2 at home however, the world seemed too bright, the sidewalk would not stay still. No one else was squinting at the too bright sun. No one else swayed. Their sidewalks appeared to be stable. Perhaps it was me. I went back inside for my shades and made my way gingerly to a walk-in medical clinic. I removed my shades, the doctor looked briefly into my eyes. “Go back to the hospital immediately. This is for an emergency CAT scan,” he said, handing me a slip of paper.

No one else was squinting at the too bright sun. No one else swayed.

An hour or three later, the procedure was completed and a white man in hospital scrubs raced into the examining room waving a gray scan, “Nothing obvious,” he told me, “but stay at home for two weeks and follow up with your general practitioner.”

I returned home, the sidewalk tipping generously from left to right. The sun was a piercing, bright light. I called my brothers, they laughed. I laughed. It sounded ridiculous. Tent pole up my nose.

A

Date of Injury (DOI): March 19, say the medical records.

“Post-concussional type syndrome resulting from a very focal injury” wrote Scott McCullagh, MD, neuropsychiatrist. Brain Injury Clinic at Sunnybrook Hospital. He’d never seen such an injury. A blow to the inside of the head.

“It is called ‘mild,’” he said apologetically, knowing full well the catastrophic impact it was having on my life. I was suddenly disabled and could not work. I slept a lot. I went for short walks. I made simple meals for my daughter and me. I swept the floor. I went to appointments.

Eventually the thought arose, perhaps from my gut, that this might be an appropriate time to get a puppy. My daughter had been asking for one for a year or was it two. I was now available for the care of a baby dog. It would sleep a lot. It would need very short walks. Just like me. I would be home when it needed to pee hourly. My daughter, now eleven, was also old enough to participate in dog care.

Two months after the DOI, on May 9, I brought Jazz home.

B

On that day in March, we had been trying to create a paradise for the children on a city beach. Two women dreaming of a campout with tents and books and games for the day. We’d imagined the children snuggled in the tent, with sand and cool, fresh air just beyond the seuil.

Jacqueline and I had bonded on the sidewalk in front of Lansdowne Public School, where we waited for the buses that would to take our kids to schools in other neighborhoods. Despite our vastly different economic positions—she owned multiple houses; I owned not much—we shared, among other things, Caribbean parentage and a deep wound. The educational systems in our respective homelands, hers England, mine Canada, had ignored two little Black girls, seeing us in one dimension and relegating us to invisibility, our giftedness unnoted. Our folks, schooled in the Caribbean, had left the advocacy for our best interests to the teachers, as was common there. They were busy navigating their new work worlds. My nurse-midwife mother, trained in natural childbirth in the Caribbean, had been told, among other things, “our women don’t give birth like that.”

We shared, among other things, Caribbean parentage and a deep wound.

We’d invented weekly Mastery Meetings, where we’d list what we’d accomplished personally, how we’d developed as people, the challenges that we’d vanquished, the smiles that we’d maintained, the courage that we’d exhibited, the tears and the tears and the tears that we’d shed.

Eventually, Jacqueline launched Anancy magazine, an online publication that highlighted Black artists. She provided me with a carte blanche to follow my interests. I wrote about music and dance and other elements of culture and spirituality.

We continued to meet and list what else we wanted to create. I was looking for Stillness. I wanted the struggles to stop. The racing. The demands on my being that were relentless. I wanted the blows to go away and allow me to—just—be—quiet. And so they did. Perhaps the spirits took control. Be careful what you ask for. Be specific.

A

My mother sat on the red couch nestled between two dark wood end tables. She’d flown in to check up on her concussed daughter. She was in nurse mode, observing me carefully while trying to hide her concern. My daughter and I stood with our backs to the stone wall in the living room, each holding a violin. One of us took a sharp sip of breath at the “and” after the fourth beat and we began. The Suzuki system requires that a parent also learn the instrument to accompany, inspire, and encourage the child, and I’d bought myself a midlevel Czech violin and enthusiastically learned along with her. That night, we played a gavotte for my mother. Then I played a solo. Then my daughter soloed. We did two more duets.

I made no mistakes that night. I played with a joy, ease, and precision that I’d never experienced before or since.

Oliver Sacks wrote in Musicophilia that brain injuries can remove inhibition. Whatever limiting habits we carry in our thoughts and beliefs can be lifted when the brain stops its usual patterns. We can become disinhibited. And something pure and wonderful has an opportunity to flow through us. My savant moment lasted about twenty-six minutes.

B

Jazz was a little savant herself. We’d trained her to bat a bell hung at the front door, with her paw, to tell us that she wanted to go out. As my daughter ran to open the door, Jazz ran in the other direction and threw herself onto a coveted spot, the blue beanbag chair. She made us laugh.

In Doctor Dogs: How Our Best Friends Are Becoming Our Best Medicine, Maria Goodavage explains how dogs can be trained to predict a migraine or a drop in blood glucose levels in the microseconds before these events come to human awareness. They are particularly effective in helping regulate our emotions. Experiencing supreme love can decrease anxiety and increase quality of life. I learned this during the year of concussion, the first year of Jazz’s life. The two of us walked for as long as my brain could handle the complex work of moving through space and time. She sported a bright-red leash and I, an invisible injury behind sunglasses that highlighted my sun-infused brownness and facial structure. We strolled through the late spring mornings and afternoons for minutes at a time. Each venture was followed by hours of rest for us both.

A

Years later, once again Jazz provided what might formally be called animal-assisted therapy or animal-assisted interventions. During Covid lockdown, her existence gave me a reason to wander through the deserted streets. It was my duty to keep her exercised and allow her to relieve herself. As I cared for her, I cared for myself—walking for hours through the distress of a shattered relationship, a dying father, isolation, and the daily trauma of Blackness in North America.

In social isolation, I wrote only while accompanied by Coltrane. The music held me in its boundless, firm, and nebulous structure as I dug into that which is not knowable, better at times forgotten and yet so integral to one’s path that it lingered, hovered, shimmering just above my head. I was held in Coltrane’s leaps and hovers. As the outside world shuddered and stumbled, I lived inside his Classic Quartet.

Coltrane’s music held me in its boundless, firm, and nebulous structure as I dug into that which is not knowable.

“Coltrane’s sound rearranges molecular structure,” said Carlos Santana in the movie Chasing Trane. That explains it, I think. The album was my external path to disinhibition. It was a better route than a blow to the head. It allowed the ghosts to come forth. An imposed quiet of a brain injury held me then. The imposed stillness of this time is familiar. The streets are empty and yet, this time, I am not alone in my distress. This time, the world is with me. Everyone’s sidewalk tilts.

A+

A shaman said that the blow to the left side of my being had been a blow to the sacred feminine. A deep wound that is now healing. “I’ve found you’ve got to look back at the old things and see them in a new light,” said Coltrane. I think he lived somewhere ecumenical and beyond labels and scriptures. Perhaps he would have understood.

I was lucky. I recovered from the concussion. Well, there are a few behavioral vestiges: I give over to the invisible. To intuition. To spirit. I move fast, knowing for sure that it is okay to be gone before the incident begins. I change my mind. I drop in a French word in conversation. Right word. Wrong language. I am sensitive to light and will continue to read even as evening falls, until I am comfortably wrapped in darkness. Like my dog, who changes direction abruptly to pull me home, long before I’ve consciously decided to do so, I’m left with the ability to discern the unspoken, any subtext, and most bullshit.

Outro

Today we walk the silent streets. Jazz is deliriously happy to be outdoors. We cross the road to avoid the droplets of breath in a jogger’s slipstream. Sirens careen around us. I hold the red leash. She pulls suddenly to throw herself enthusiastically onto a patch of grass that holds molecules of shit and urine left by others of her kind. She still does not fetch.

We walk to the spot of sand on Sunnyside Beach where I was injured years ago. It is 7:30 a.m., before the hordes of sunseekers and quarantine-avoiders arise. There is now a groomed and fenced butterfly garden at the site. No dogs beyond the fence, says a sign. There are warnings encouraging all to stay the distance of three geese apart. And oh! a paddleboarder drifts by—and another. Jazz sees them first. She is not held up in thought. She lives in disinhibition. She is my teacher at times. And sometimes I remember the lesson.

The world is rewiring itself. It is revealing the interstitial spaces between each atomic note.

Jazz is with me still. Coltrane has my back.

Toronto, Canada