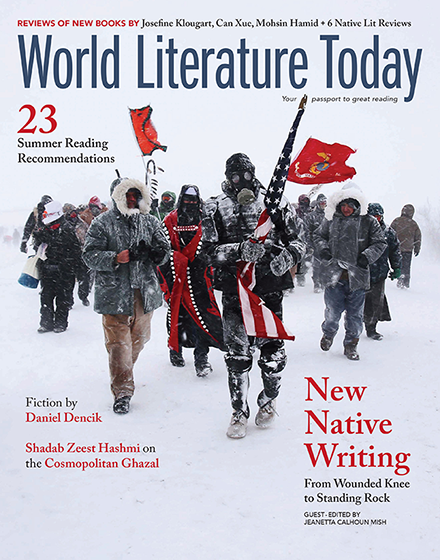

Captivity

I.

A mark across the body. The morning I watched my beloved uncle disappear down the alley. His car left sitting in our yard for thirty days. This tattoo we cover with shame. The stories my mother whispered as if gitchi-manidoo was a child who should not be told of the troubles of humans. All those taken. Visits made on dusty trains. Letters adorned like birch-bark art with lines and tiny holes. My shriveled grandma “an accessory” hiding my cousin from the interchangeable uniforms of civil pursuit.

Her white hair another flag of truce.

II.

This is how we look over our shoulder. This is how we smile carefully in public places. This is how we carry our cards, our identities. This is how we forget—and how you remind us.

III.

Mary Rowlandson made it big in the colonial tabloids. Indian captivity narrative a seeming misnomer. But ink makes strong cultural bars of bias. This is how we remain captured in print.

IV.

Now I harbor fugitive names. c sin came to my reading in ankle tether. Qu i chained herself before the R C building in protest. M cus who cannot receive email. The Ar tc at manager from Thi f ive ls. His whiskey-inspired stories tell of cicada existence—a cyclical shedding of “dangerous” identities.

V.

We molt. The shell of our past a transparent chanhua. Yes, we will eat it like medicine.

More by Kimberly Blaeser

Table of Contents