Vital Kinships: A Conversation with Eric Gansworth & Arigon Starr

A central yet surprisingly undernoted facet of Native arts production is its interrelationality. Whether innovating across genres or moving across expressive forms, many Native artists refuse to settle. In doing so, they make visible vital kinships between visual and verbal forms, between image and text. Arigon Starr, a comics artist and musician, and Eric Gans-worth, a painter and writer, exemplify the dynamic multiplicity at the heart of contemporary Native aesthetics. This interview, begun with Arigon at the Indigenous Comic Con in Albuquerque and concluded via lively email exchanges, was fittingly interactive. Following Eric’s suggestions, I asked each of them different questions. They then shared their responses, prompting more exchanges. Our ensuing asynchronous conversations are represented in abridged form here. Although they have not yet met, Arigon and Eric found ample interconnections, both in their work and in their affinities for nerd culture and 1970s rock stars.

Comic Origin Stories

Susan Bernardin: Whether we define the comics medium in Scott McCloud’s words as “juxtaposed pictorial images and other images in deliberate sequence” or as a form of visual storytelling, it has proved a generative source for both of you. What role did reading and writing comics play in your development as an artist? What were its stylistic, narrative, or structural elements that appealed to you? In what ways have your tribal nations’ forms of visual storytelling influenced or enhanced your aesthetic?

Eric Gansworth: I came to comics through TV, latching onto Batman before the age of two. As soon as I could read, I leaped onto comics, and in fourth grade I made a comic, which went on display at the school (wish I still had it, but I remember it well). So, it’s always been a part of my thinking lexicon. Haudenosaunee culture is very image-driven—wampum figures carrying our culture, representational beadwork—but I didn’t really begin exploring its possibilities as a refractory lens until the beginning of my professional career. I was always aware of those images. From day one, giant electrical towers looked like monstrous wampum men towering over our landscape.

Arigon Starr: There have always been comic books in my life, from Sunday funnies to Archie to superheroes. I started drawing my own comics in junior high, often featuring my favorite musicians of the time (yes, I made George Harrison into a superhero called “Hippie Man”). My tribal influences came from seeing artwork from Oklahoma artists like Acee Blue Eagle and Solomon McCombs (both from the Muscogee Creek Nation), who used a flat color rendering style with thick, traced outlines. Those paintings looked like Indian Comics to me! Additionally, my Kickapoo uncle Rudolph Wahpecome was an artist and architect, so I knew that an Indian might be able to make a living as an artist.

Afterlives and Novel Forms

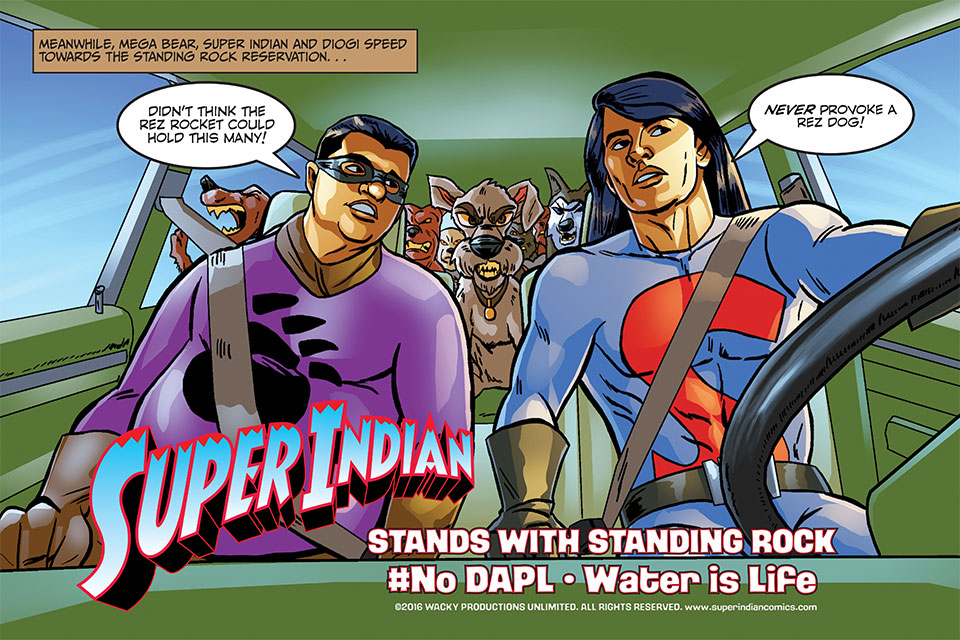

Bernardin: Although contemporary Native artists and writers often work in multiple media, you two are unusually ambidextrous: Arigon, you are a musician, playwright, and comics artist. Moreover, your Super Indian, like any good superhero, has many lives, moving from a radio series to serial web comic to published volumes. Eric, you are a painter, poet, and novelist whose books feature interrelated visual and narrative designs. The vital, complex kinship between literary and visual forms is a signature feature of your work.

How do you each perceive the relationship between the moving parts or platforms of your work? What does each offer? What kinds of work do you see each performing? How do you see these different platforms or forms engaging different audiences?

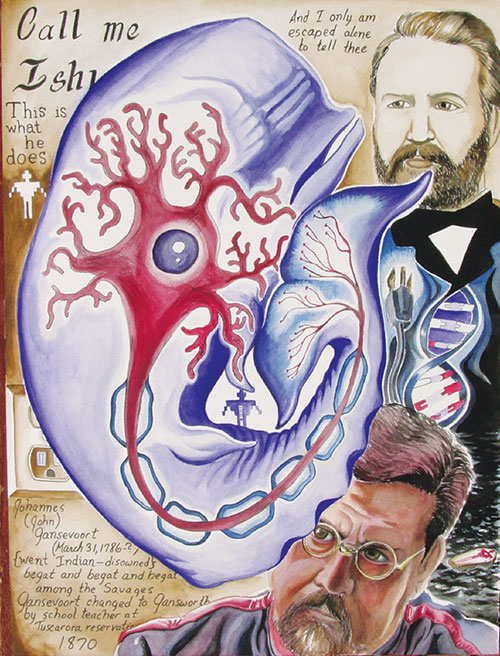

Elemental Gratitude: Water (2010), gouache on paper,

24 x 18 in / Courtesy of the artist (www.ericgansworth.com)

Gansworth: Comics prepared me for flexing both sides of my voice. While I compose differently, visual and verbal forms are all the same story to me, filtered through different facets. Maybe it’s close to performance artists like Laurie Anderson and Karen Finley and progressive bands like Rush and Pink Floyd. Long before music videos, both bands explored the synthesis of simultaneously presented images and songs. I also (being a weird kid) loved early German expressionist silent films. By the age of nine, I‘d seen Nosferatu and Metropolis multiple times. They relied on the visual with extremely economically written intertitles, closer to reading wampum belts than you’d think. Also, in Tuscarora language class, we played language tic-tac-toe. In kindergarten, we could draw the item. So I quickly learned the word for bat, skeleton, etc. I had to learn Tuscarora words for things I wanted to draw on the board—word and image, inextricably linked.

Starr: Like Eric, I watched a lot of television growing up. My parents watched everything from the original Star Trek to westerns like Gunsmoke. Later, I found Monty Python and Saturday Night Live. Humor was big in our household—and I never heard my father laugh harder than at shows like The Jeffersons or movies like Blazing Saddles. Humor and weirdness crept into my music. I wrote love songs to Spike, the punk-rock vampire from Buffy, the Vampire Slayer, and a tribute to the Joan Collins’s Star Trek episode “City on the Edge of Forever” (written by the amazing Harlan Ellison) in “Edith Keeler Must Die.” Musicals and westerns converged into my one-woman show The Red Road, where a country music singer comes to Sapulpa, Oklahoma, to tape her tenth-anniversary TV show. With Super Indian, referencing pop culture like Star Wars or the exploitation flick Billy Jack is a way for non-Indian readers to connect with these wacky Rez Kids.

With Super Indian, referencing pop culture like Star Wars or the exploitation flick Billy Jack is a way for non-Indian readers to connect with these wacky Rez Kids. – Arigon Starr

Consequential Arts

Bernardin: Just as the interrelationship of the visual and verbal offers audiences multiple portals to access your stories, your stories offer readers varying levels of access depending on their knowledge of diverse references, ranging from wampum to Star Trek, Pink Floyd to commodity food. What kinds of knowledges do you want to highlight in your stories? How does this rich mixing of referents shape the interactive relationship you create with your readers?

Starr: Super Indian and all my writings (plays, music) were designed to counter negative Native stereotypes. As long as mainstream culture keeps churning out phony Tontos and insulting Pocahotties, I’ll keep creating fictional Native characters that have real-life counterparts. When folks see those stereotypes, I do my best to make them look as unattractive and fake as possible. This lets the audience into my world, in on the joke, and hopefully they begin to feel like co-conspirators. Because I was raised across the United States and overseas as the daughter of a career Navy man, I was often the only Indian person in my school classes. Having the constant “other” spotlight on me taught me the importance of representing Native people in a good way. Those experiences have shaped my works, especially the characters in Super Indian. They are of the reservation but have feet in two worlds through mass media.

As long as mainstream culture keeps churning out phony Tontos and insulting Pocahotties, I’ll keep creating fictional Native characters that have real-life counterparts. – Arigon Starr

Gansworth: Agreed. I always engaged a pop culture sensibility because it represented the Rez world as I know it. My first published short story featured plastic Indian figures, and personal circumstances made my early awareness of non-Rez life mediated only through TV, comics, movies, and music. I swear there’s a Billy Jack hat requirement on the Rez!

Smoke Dancing (2004), oil on canvas, 48 x 36 in /

Courtesy of the artist (www.ericgansworth.com)

Memory Banks

Bernardin: Arigon, Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers makes visible the little-known stories of codetalkers from different tribes in the major wars of the twentieth century. This task in large part involves activating intergenerational memory. Eric, your novels and poems frequently hinge on the fragility of intergenerational memory, a testament to losses both personal and collective, both familial and territorial. In response, through structures of memory in your paired paintings and stories, you voice the imperative to remember. What is visual storytelling’s role in sharing intergenerational knowledge? How do your works activate memory? What is the relationship between restoring indigenous historical memory and imagining indigenous futures?

Starr: Connecting historical memory and indigenous futures comes from showing that Native people have always been here and will continue to survive. It reminds me of looking at old photographs of my kinfolk from the 1950s and 1960s and seeing them looking all trendy and vintage, just like something you’d see in Mad Men or L.A. Confidential. It’s a privilege to have opportunities to tell inclusive stories about Indian folks from across the US in various media. Current films like Hidden Figures (African American female engineers, mathematicians, and computer pioneers during NASA’s early days) give me hope that we’ll get our turn to tell stories about Dr. Susan LaFlesche-Picotte, the first female Native American doctor, or someone like John Harrington, the first Native in space. In the meantime, I will continue to champion our people in my words, music, art, and deeds.

Gansworth: I’m a terrible researcher for things I’m writing about. The one time I really had to do research, to understand treaty tax law, I hated it. My most fruitful research method is grounded in intimately personal connection. For me, personal objects, touchstones, help. I talk to people, and my workspace is filled with pop culture artifacts from when my life’s emotional timbre was honed.

I noticed such familiarity in Super Indian’s characters. I wondered if those faces were from real people. My paintings are full of family members, as iconic cultural figures. It’s important to me that those icons have connections to current, complex lives. A story without living connections is just history. There’s nothing wrong with history as a life’s passion—it’s just not my life’s passion.

It’s important to me that those icons have connections to current, complex lives. A story without living connections is just history. – Eric Gansworth

This sounds so “Indian cliché,” but this career philosophy was a direct result of a conversation with an elder. My friend’s dad said to me one day: “Have you ever captured the Real Junebug?” (my uncle). He said, “We’re not gonna be around forever. You’re the one who can draw us, and you should while we’re still here.” Junebug died in 1992. That year, he became a character of mine. He’s still there. Capturing generic “Native America” is easy, and it’s easily digested in its familiarity. Capturing real people, well, that’s another matter.

Representational Activism & Imaginative Sovereignty

Bernardin: Arigon, Super In-dian’s universe is the fictional Leaning Oak reservation. Eric, the center of your narrative universe is the fictionalized Tuscarora Reservation in western New York. Your respective works present layered, complex, humored portraits of Indigenous communities, especially the deep tissue of intergenerational and interpersonal relationships. What kinds of questions, hopes, or concerns animate the stories you produce about these communities?

Gansworth: For me, work is always a communication between the intuitive and the carefully considered. It feels like using a Ouija board. Players insist they’re not moving it, but all feel it moving. Either there’s subconscious muscles moving, or it’s the spirit world. Imagine the horror of being a Ouija spirit! As Lynda Barry suggests, it’s often “twelve teenage girls asking the Ouija board does Donny like me.” Like Barry’s teenage girls, I write what I want to see. I was never interested in generic “Native American stories.” Tuscarora Nation is socially complicated and politically tumultuous. It has its own nuances and layers.

My novel, Smoke Dancing, concerns the effects tribal political realities have on people’s lives. One scholar felt that readers welcome the word “treaties” in Native fiction, as an aesthetic flourish, but that details of real, actual treaties on people’s lives were too cumbersome for a mainstream reader. Still, I can only write about things that speak to me. The space “between the two vessels” represented by the Guswenta, the Two Row Wampum, represents “friendship and peace, forever.” That space is still a constant negotiation, and that’s where my stories find their animation, their heartbeats, their breaths.

Starr: Eric is so right! Writing a generic Indian story is such a waste of time for me. Let somebody with questionable credentials write those. Some of the early Super Indian feedback was that it was too Indian and wouldn’t appeal to a mainstream audience. I ignored that and wrote Volume Two, which went even further into the things that divide Native folks—like blood quantum. When I tell Indians the situation of issue #5 and #6—“A vampire wants to become a full-blood Indian by biting other full bloods”—a big belly laugh ensues. I’ll go further in the next volume, taking on New Agers and outside occupiers looking for a piece of our “Rez Magic.” Life is way too short to write stories about “Am I White or Am I Indian?” or “Drunken Sad Indian Endures a Tragic Life,” which seem to always get funded. I’m excited about bringing real Indian Outlaws to life (like the novel Robert J. Conley wrote about one of my kinfolk, Henry Starr) and continuing the fun with Super Indian. There are so many worthy stories crying out to be told (like Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers) that it’s going to take an Indigenous Creative Army to tackle them. We better get busy!

January 2017

An enrolled member of the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, Arigon Starr is an award-winning musician, actor, playwright, and artist. Super Indian, which began as a radio comedy series, became a web comic then printed graphic novels. A 2017 Tulsa Artist Fellow, she’s based in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

An enrolled member of the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, Arigon Starr is an award-winning musician, actor, playwright, and artist. Super Indian, which began as a radio comedy series, became a web comic then printed graphic novels. A 2017 Tulsa Artist Fellow, she’s based in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Eric Gansworth / S⎧ha-weñ na-sae (enrolled Onondaga), a writer and visual artist from Tuscarora Nation, is employed by Canisius College. His books include If I Ever Get out of Here, Extra Indians (American Book Award), Mending Skins (PEN Oakland Award), and A Half-Life of Cardio-Pulmonary Function (NBCC Good Reads List).

Eric Gansworth / S⎧ha-weñ na-sae (enrolled Onondaga), a writer and visual artist from Tuscarora Nation, is employed by Canisius College. His books include If I Ever Get out of Here, Extra Indians (American Book Award), Mending Skins (PEN Oakland Award), and A Half-Life of Cardio-Pulmonary Function (NBCC Good Reads List).