Conversations at the Edge of Carnage

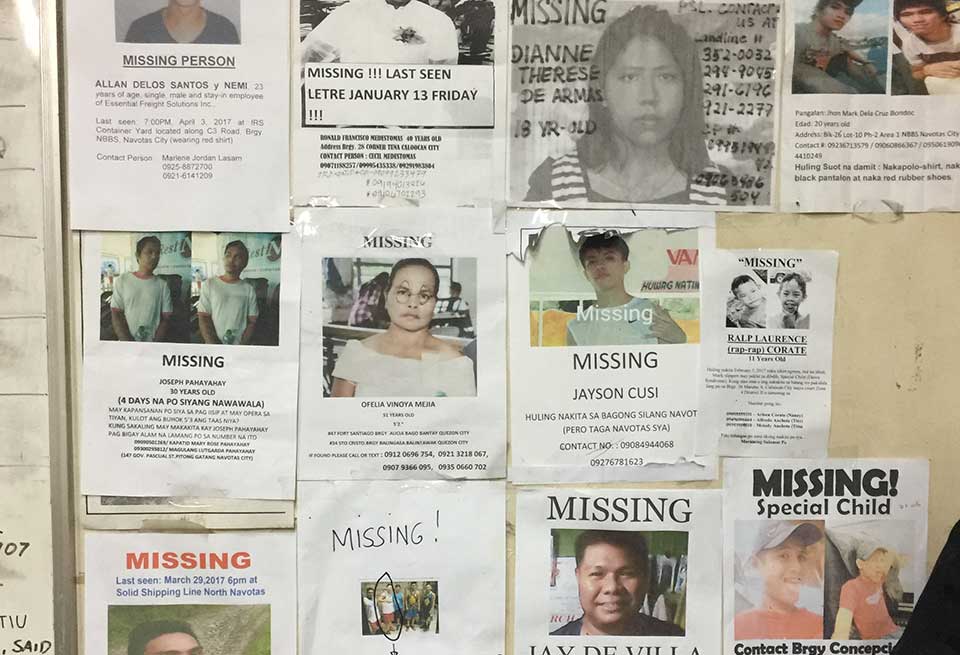

The missing persons bulletin board at Navotas City Police Station in Metro Manila, June 2017. Photo courtesy of the author

The missing persons bulletin board at Navotas City Police Station in Metro Manila, June 2017. Photo courtesy of the authorDo so many opportunities to bear witness only create opportunities to turn away? To harden our gazes and retreat into our own narratives?

Dr. Gina Hechanova felt wary of the candidate Rodrigo Duterte’s rhetoric during the 2016 election season. As an organizational psychologist familiar with medical interventions for drug users, she worried Duterte might make good on his promise of a murderous policy. But she felt cautiously hopeful after his win. She wanted to give the new leadership a chance.

Two months into Duterte’s term, Dr. Hechanova watched bodies appear in the street and read hundreds of comments online from Filipinos supporting the drug war as progress. She set filters on her social media accounts and despaired.

“It was the first time I regretted coming home,” she says; “home” meaning, as it always does, for her, the Philippines.

She had the chance to remain in Michigan after finishing her PhD in the nineties, but she returned to her home country to work against the trauma of poverty and neglect in exploited, low-income communities. Now she worries about her four children, and what brutal version of the Philippines they might inherit. She tells me there was an early-morning murder near their home in Metro Manila, so she no longer allows her household members to go alone into the street at night.

“Have you seen Wonder Woman? You can do nothing or you can do something. This is my something.”– Gina Hechanova

In a small seminar room at the university where she works, I asked why she stayed. Dr. Hechanova smiled a familiar, rueful smile I saw often from Filipinos exhausted by, but remaining in, Duterte’s Philippines.

“Have you seen Wonder Woman?” she asked. “You can do nothing or you can do something. This is my something.”

She pilots community-based treatment programs now, hoping to show the country alternative ways to regard individuals using drugs. She hopes her efforts will slowly halt the murders, if only in a few neighborhoods. She is not sure what is possible, but still. She stays. She tries.

More than a year after President Duterte’s landslide victory in the Philippine elections, Filipinos across classes and political divides have readjusted to the new era with varying degrees of faith or distress. As a dual Filipina-American citizen who now lives in Singapore—the low-crime nation many Filipinos wish to emulate—I also watched the rise of Duterte with a terror that seemed confirmed by an epidemic of homicides.

But filled as I am with dread and anger, I am in the minority. Surveys even show that while many Filipinos are now skeptical about the Philippine National Police’s claims that their shooting victims “fought back,” most Filipinos still approve of Duterte’s governance.

In July 2017, after talking to Dr. Hechanova, I talked to one supporter two years younger than me. Thirty-one-year-old security researcher Drei Toledo has steady faith in Duterte’s leadership. She’s met him in person and shaken his hand. She was once a believer in People Power, the movement that ousted the Marcos dictatorship in 1986. But she explained that her politics changed when she witnessed the abuse of farmers at Hacienda Luisita, the plantation owned by the family of former president and People Power ascendant, Benigno Aquino III. Duterte was also a good mayor, she thought, who sympathized with her passion as a feminist to stop violent abuse against women and children.

If Duterte were to declare martial law, giving the police and military more power to act against what they call threats, I anticipate innumerable more devastated widows and families.

As we ate together at an Italian trattoria in a middle-class neighborhood of south Manila, I asked Ms. Toledo how she felt about Duterte’s near-constant rape jokes and the skyrocketing homicide rate during his first year in office. Toledo argued that the drug war was necessary to contain rampant crime, and that the numbers of the dead were problematic and mischaracterized, in part, by a corrupted local and foreign media who sought to undermine the presidency. She does not believe in the validity of assertions that any killings are state-sponsored; she knows personally of peers who sold drugs and are still alive after surrendering. She asserted that killings of journalists themselves were much lower than in previous administrations and credited Duterte’s Presidential Task Force on Media Security. She gazed at me as I took notes and recorded her voice.

“All he cares about is that you’re safe,” she told me, and I fought hard to keep my face still.

Toledo went on that she loved, too, Duterte’s open ear to Filipino farmers and his implementation of ordinances preventing sexual harassment during his time as mayor of Davao City. While Toledo recognized the contradictions in Duterte’s nature, she trusted his actions, and if he were to impose a much-rumored national policy of martial law, she would support it.

I would fear it. I fear it now. I feared that Toledo’s framing—an interpretation put forth by other Duterte supporters—was giving armed men their justifications to destroy unarmed human beings in the country each night.

But if I were to say those fears aloud, I think Toledo would have counted me among the manipulated, and manipulative, media. I wondered if I would have an army of Duterte supporters harassing me on my social media accounts.

So I listened and took notes. I paid for our pizza. I changed my profile photos to hide my face. But no one has come for me, not yet.

*

Toledo’s optimism and trust could not have felt more remote to me seven hours later, when I visited the outdoor wake for forty-three-year-old Jimmy Predas.

On a dim street of Caloocan, one of the lowest-income neighborhoods of Metro Manila, neighbors and relatives played cards under outdoor tents to raise money for Mr. Predas’s burial. His widow, Amy Predas, a forty-two-year-old office administrator, sat on a white plastic chair with her back to her former husband’s casket. She kept a thin hand on the inner wrist of her teary, twenty-year-old son, Lester, her gaze empty and dazed. Lester kept a small white towel in his fist, wiping his eyes every few moments.

Plainclothes policemen shot Predas in his small plywood and cinderblock home near midnight on June 23. Lester witnessed the killing. The officers had screamed at him to lie face down on the concrete before aiming their guns at his father’s bed. He told me Predas was still sleeping when officers shot him multiple times.

Jimmy Predas had the unusual stillness of the dead, a heavy cake of light brown makeup on his stiffened face. The sad phrase came to me.

But, as with thousands of other reports, the police report called the death a legitimate act to protect officers’ lives. The killers said Jimmy Predas was armed. Lester says they dropped a gun next to his bed. He said the family could never afford a firearm.

The plainclothes police officers stared at Lester as funeral workers carried his father’s body out of the house, their menacing gazes a warning to him, the sole witness. A local news photographer told him to leave the neighborhood for a while, for his own safety. So Lester did. But he was back now, mourning with his mother at the wake.

Lester kept a bag of his father’s bloodied sheets in a bag, next to the bed where his father died. He hadn’t found himself able to throw them away.

Amy Predas worried about how her children would continue their schooling; Mr. Predas had supported them diligently as a tour van driver and newspaper stitcher. She said he liked to sing karaoke, and that he liked to eat pork dishes with their children and grandchildren.

She paused, weeping, when she remembered his singing voice.

She wondered if the government would ever offer compassion for her loss. She oscillated between shame and anxiety. She worried what her coworkers might think of her, for having a husband murdered by police.

She had voted for Duterte because she hoped he would broker peace. She trusted that he would halt the supply of drugs her husband sometimes used.

I asked if her if she had ever experienced violence before—a central belief of drug war supporters is the necessity to curb the potential violence of drug addicts.

But Ms. Predas said, “No. Never in my life,” and her face crumpled with grief.

If Duterte were to declare martial law, giving the police and military more power to act against what they call threats, I anticipate innumerable more devastated widows and families.

I wondered if Drei Toledo would ever come on the night shift to visit with these families and hear their contradictions of one police report after another. Would her heart shift, as it had after seeing the violence at Hacienda Luisita? Is looking and listening enough? There are more videos and accounts of atrocity available more quickly than ever before in history, in every imaginable medium. But do so many opportunities to bear witness only create opportunities to turn away? To harden our gazes and retreat into our own narratives?

I stood and looked through the plastic cover of Predas’s casket. He had the unusual stillness of the dead, a heavy cake of light brown makeup on his stiffened face. The sad phrase at least came to me.

At least the plainclothes officers who killed him did not damage his face. At least the family knew the names of his murderers. At least anonymous killers had not tortured him with the stabbing of an ice pick or suffocation by masking tape. At least Jimmy Predas did not float to the filthy banks of the port nearby, bloated after the killers dumped him. At least he was not missing, disappeared by his killers, his face on one of the posters covering the walls of the police departments nearby. At least Predas’s family had his body.

“Condolence,” I said weakly to the Predas family, “condolence.” And I left to visit a police station.

*

Though international criticism of the Philippine National Police’s methods continues, and their dockets of unsolved murders remain in the thousands, the police I spoke to that night remain optimistic about Duterte’s rule.

Inside the Navotas City police station in Manila, in a neighborhood where murders take place nightly, I sat on a mottled white plastic bench and asked Criminal Investigator PO3 Allan Joey Ogata III what he thought of the foreign news portrayals of the Philippine National Police. He said it was demoralizing when foreign media mischaracterized the PNP as wanton killers.

“They don’t know the reality here,” he said. “They should look into the criminal backgrounds of the ones who were killed.”

He refused to comment on specific cases, so I asked what support the PNP needed in order to solve the thousands of deaths under investigation in the country—homicides committed largely by masked, plainclothes men who arrive on motorcycles. Mr. Ogata said it was difficult to collect evidence with few forensic tools; they had no fingerprint kits or sketch artists in the station.

He voted for Duterte for his promises to support the police and military, and while the PNP haven’t yet received their promised raises, Ogata was hopeful his would arrive in January.

I asked if he had anything he would like to say to the president, if he were here in the station. Ogata paused for a moment. “You have my full support,” he said. “One hundred percent.”

As I crossed the pocked linoleum floor on my way out of the station, I glanced at the screen of one officer’s desktop computer. I did not see police reports or email correspondence about the alarming rise in homicides this year. I saw a YouTube compilation video of “Funny Pranks,” set on pause.

Metro Manila, Philippines