The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story, by Edwidge Danticat

The Art of Death

The Art of Death

Edwidge Danticat

Graywolf Press (2017)

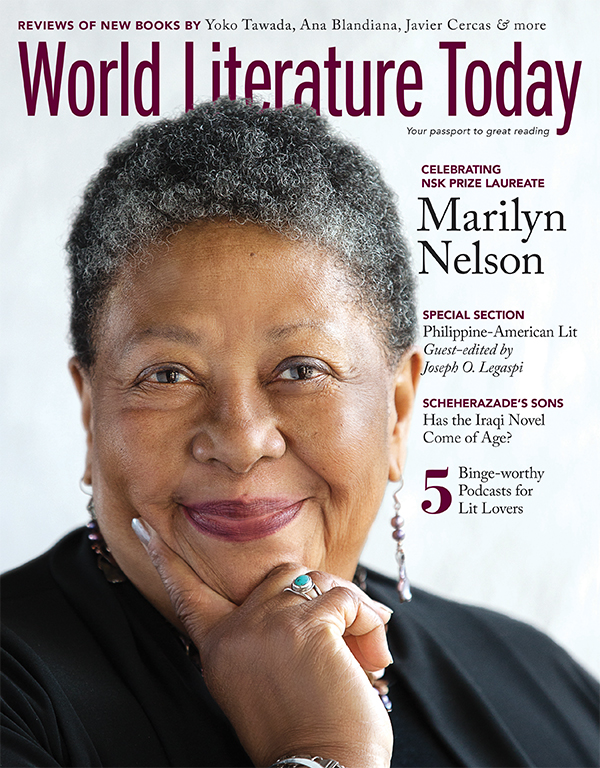

It might seem odd to focus on a book called The Art of Death as spring approaches (at least in the Northern Hemisphere), but we all know about the ides of March, and as Eliot reminded us, April can be the cruellest month. When Achy Obejas presented Edwidge Danticat as her candidate for the 2018 Neustadt International Prize for Literature last November, she spoke so glowingly about the essays included in The Art of Death that I was compelled to track it down. The roomful of writers assembled at the University of Oklahoma to select the prizewinner ultimately chose Danticat—who is best known for her fiction about the Haitian American experience—as this year’s laureate.

These compelling essays mostly deal with writers’ fictional depictions of death, but the opening and closing sections bookending the collection—and many of the passages in between—read like a love letter to Danticat’s mother, who died of ovarian cancer in 2014. Accompanying her mother to “lòt bò dlo” (the other side of the water) as her Creole interpreter while assuming the role of principal caretaker at the end of her life, Danticat weaves communal as well as literary responses to death into her own private meditations on loss. In a moving image, Danticat describes the “reverse pietà” of propping up and comforting her mother’s body with her own.

While the personal scale of death preoccupies Danticat, large-scale losses of life—massacres in Haiti and Colombia, earthquakes in Japan and Haiti, 9/11—also precipitate writerly responses. Meditations on mortality from more than two dozen writers are artfully woven throughout the book, with canonical examples alongside less well-known writers like Taiye Selasi, Reetika Vazirani, and Mary Gordon.

For Danticat, literary language carries a moral force that helps writers, and readers, navigate the “circles of sorrow” surrounding death. “We write about the dead,” she muses, “to make sense of our losses, to become less haunted, to turn ghosts into words, to transform an absence into language.” As Danticat’s mother tells her, “Nou rantre tèt devan. Nou soti pye devan” (Most of us enter this world headfirst, then we leave it feetfirst). Writers circumnavigate the arc in between.

Daniel Simon

Editor in Chief