Migration, My Mother, and Me

A writer undergoes a transformation while overcoming a series of obstacles as she works to reunite her mother with her mother’s siblings in the Philippines.

In the days after the 2016 election, I found myself strangely unmoored. I, like many others, was unprepared for the outcome and unsure of what to do. On the Wednesday following Trump’s victory, after a largely sleepless night of watching the various results come in, I packed my bag as I’d committed to a weeklong residency at the Vermont Studio. I drove the three hours north from my hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts, in a daze, listening to National Public Radio, first a Baptist minister explaining how President-elect Trump was acceptable despite his transgressions as the minister was not “proud of everything I’ve done,” followed by Gloria Steinem speaking about white male entitlement. The talk was all very enlightening, although it offered little hope.

Later that night, I pulled myself together to speak with my son, Nick, in his first year at Bennington College, but admitted to having no words of comfort other than to point out that he was an exceptionally smart, motivated boy and would figure out a course of action. He had turned to his mother for comfort, and it made me think of my mother, who was a woman of many opinions and little reassurance, and what she would have made of all this had she been alive to see it. As a Filipina, she would be in the group of “vulnerable citizens” that the election results had left in a precarious position—a nonwhite woman, an immigrant, a target for energetic bigotry. A note here: I am one of those racially ambiguous people, someone whose intellectual and cultural constructions are richly influenced by my Filipino heritage, but walking down the street one might think me Italian or French or Spanish, and the Continental sort of Spanish, not the “Spanish” that inspires to walls. My father is largely Irish American, with some other stuff in there, all white. Yet I know well what it is to be identified as other and, as a result, attacked. It is an informing part of my childhood.

I spent my early years in Perth, Western Australia, during some turbulent times. It was the 1970s and the Vietnam War had deposited a large number of Vietnamese refugees in our city, and the overwhelming response to this was hostile. As a child, I did not understand the larger movements of history. I was, however, familiar with the fenced enclosure where many of the refugees were housed. I remember driving by the camp, although infrequently. It was not close to where I lived. Once, as my father and I were on our way to a rugby match, the car was stalled in traffic, and I made eye contact with a boy close to my age whose fingers were loosely hooked through the wire that kept him imprisoned. The exchange was silent but meaningful. My look no doubt communicated, “What did you do?” His eyes replied, “You’re going somewhere and I’m not.” Or perhaps the boy was not Vietnamese but rather Timorese, because in those years we also had the “boat people,” who were fleeing the strife in East Timor. No doubt many sympathized with their plight—the fact that they were given sanctuary attests to this—but to hear people speak of the refugees, one would have thought these desperate families to be a plague of locusts.

Once, while waiting for a bus with my mother, a man yelled at us, “Go home.” I asked my mother what he meant, because we were weighted down with shopping bags and it was fairly obvious that home was exactly where we were headed. My mother, not one to sugarcoat, said, “He means Vietnam.” And I might have asked her why we would go there, but I sensed the ugliness in her response, an ugliness that I was hesitant to pursue. There were other incidents, kids on the playground taunting me that my mother was a boat person, more yelling on the street. My mother was a woman who commanded respect and had many friends, but in her interactions with the various shopkeepers and some of the school parents, there was a lingering sense of her otherness, and not the “otherness” inspired by her singular personality, but some other thing—her foreignness—that inspired a wariness in me.

No doubt many sympathized with their plight—the fact that they were given sanctuary attests to this—but to hear people speak of the refugees, one would have thought these desperate families to be a plague of locusts.

My mother never learned to drive and as a result was always walking or waiting at bus stops, easy prey. There was a story she liked to tell of how she was planting petunias on the perimeter of the front footpath and some idiot walking by had called to her, “Indian woman, dig-dig-dig.” She thought this was hilarious. What might have been a deeply dark time for my miscegenated family was somewhat offset by my mother’s unflagging sense of superiority to most of those around her, by her conviction that the West was undeniably inferior—culturally, socially, aesthetically—to the East. That brio was not lost on me, but neither was the reality that many around us wished us ill.

When my family moved to the Philippines in the early 1980s, the situation altered significantly. My mother’s family lived in great houses with battalions of servants. This was my mother’s country and she fit the fabric; even if she hadn’t, she was not walking nor waiting at bus stops. She still did not drive, but we had a chauffeur who performed that task. She was not vulnerable, but in an odd turn of events, that identifiable victimhood had passed to her daughters. Light-skinned, tall, and pretty, I found myself the target of comments. Men would call to me bangus, which is most often translated as milk fish and is appreciative, but not of a complimentary nature. There were other salacious comments from which I was nominally saved both by my innocence and my poor Tagalog, but I could sense their meaning, and the powerlessness I felt in those moments was real and created a vibrating terror, even though I was not physically at risk. I could say here that the colonial history of the Philippines demands a certain patience with this sort of repartee, but the comments were racist, misogynistic, and vile. Although I love the Philippines—my family, the culture, even the traffic-glutted, pollution-cloaked nightmare that is Manila—it was a relief when I left for college in the United States. Walking down an American street, the fact that I was unremarkable made me feel an immense safety.

In the early 2000s, in another of my family’s epic moves, my parents came to live in South Freeport, Maine. My mother did not fit in there, but as her singularity in many other ways had increased with age, her exceptionalness was more symptomatic than defining. She had no desire to be a part of anything and kept herself occupied with house accounts, with occasional forays to the supermarket and to church, with running a household that included my sister and her son. She had a very full life. Then she fell ill with Parkinson’s, and keeping busy was no longer possible. The window for a trip to the Philippines was closing as the disease advanced, and I began to make plans so she could be reunited with her siblings one last time.

I looked at the invalid document, at the three holes that were punched into it, at my mother’s picture, at the expires 7/2002, and I wondered how we would manage to renew her green card and her passport by five p.m. the following day.

My mother, proud to be Filipino, never changed her citizenship despite her American husband, American children, and American life. She still had her Filipino passport. I booked the flights and contacted relatives and thought all was settled when I discovered, with some dismay, that her Filipino passport had lapsed nearly a decade earlier. Some research revealed the disheartening truth that the only solution was to make an appointment, and soon, with the Philippine Consul in New York. And my mother—no budging on this—had to be present. This would not be easy because, in addition to my mother’s general shakiness and fragility, she was also suffering from a hard-to-ignore dementia. But I was determined, so my sister filled out forms and assembled papers, and my father drove the first leg south to Amherst. My plan was to drive to New York the following evening, spend the night in a hotel, go to the consulate first thing in the morning, and then drive back to Massachusetts in the afternoon.

On the drive, my mother was in good spirits. At regular intervals, she would ask me where we were going, and why. The idea of going to New York appealed to her, and then appealed to her again. A song came on the radio and I said, “Nay, it’s Bruno Mars. He’s Filipino.” She said, “And they like him?” “He’s very popular.” And she said, “Mars is not a Filipino name.” And I said, “Is Bruno?” And she said, “Yes.” She also kept asking me if, in New York, there would be fried chicken.

And all would have been equally lighthearted and convivial if I had not discovered—as I did somewhere around ten that night—that her green card, like her passport, had expired. I returned to the file several times, hoping that another, current green card was lurking there, but with no luck. I looked at the invalid document, at the three holes that were punched into it, at my mother’s picture, at the expires 7/2002, and I wondered how we would manage to renew her green card and her passport by five p.m. the following day. A call to my sister confirmed that this was the only green card they had, although a more recent one might be lurking in the avalanche of papers in my mother’s room, but she was unable to locate it. A call to the INS—Byzantine and incomprehensible to this professional practitioner of English—did not encourage. But the following morning, after muffins and juice, I dressed my mother, put her in my down coat as it was very cold, and took a taxi to the Immigration Center in lower Manhattan.

By the time we arrived, it was ten o’clock and the line was reaching around the block. I was beginning to understand how hard it was not to be a citizen, but the atmosphere in the queue—with its Russians and Nigerians and Chinese and Salvadorans—was strangely festive. I was waiting with a group of people used to waiting and no one complained. My experience with the INS was—strange but true—marked with kindness, first by the young Vietnamese American who fast-tracked an appointment (it usually takes six weeks) and then by the official—an African American from South Carolina—who created a temporary green card for us and responded to my mother’s, “Do you know where we can get fried chicken?” with a big laugh and the suggestion that we try the food court at Safeway.

What little hope I had, and I could feel the creep of it, was rooted in the reality that this nation was built on conflict, and that the Declaration of Independence, with its equality for all, was not an element of the country’s makeup but its soul.

The reason that I tell this story is that I exited that building a different person than the one who had entered. Privilege shelters you, and mine—enough money to be middle class, enough learning to write books, a birthright guaranteeing my place in the United States—had sheltered me. But I had spent a small amount of time with people who lacked at least the third of these privileges, who had faith that their decision to live in the United States was what would best allow them to thrive. I hoped everyone in that seemingly endless, snaking line would be as successful as my mother and me. I hoped that they would get to live in this great country where young men were moved by a desperate woman’s desire to bring her mother to her siblings one last time, where a man could momentarily sidestep the trappings of racism to laugh with an old Filipina woman, a country where all were safe and wanted and free.

In the days after the election, I was unmoored. I was unsure of how to remedy the situation but felt an undeniable responsibility. I felt as if I’d spent the last eight years drunk on optimism, an optimism that, as with all true benders, left me feeling an untethered guilt—a suspicion that I must have been doing something wrong to wake on this morning feeling so unnerved. But what little hope I had, and I could feel the creep of it, was rooted in the reality that this nation was built on conflict, and that the Declaration of Independence, with its equality for all, was not an element of the country’s makeup but its soul. I knew my sense of desperation was an indulgence, one that I would have to overcome and soon. I was living in a country that no longer represented my beliefs, although a majority of citizens felt much the same as I did. Soon we were going to have to fight, to realign, to redefine. I said to myself, “Tomorrow.” And then the next day, I said, “Tomorrow,” again. But all around me people were starting to find their voice, and hope—that little, pretty, whispering horror—had found a place, even in this deranged world.

UMass Amherst

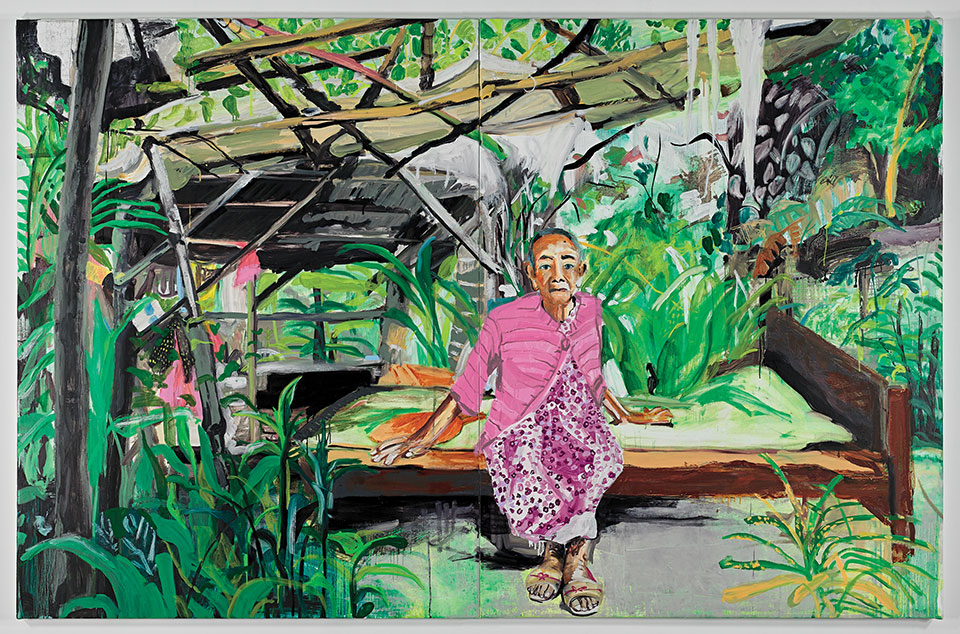

Maia Cruz Palileo (www.maiacruzpalileo.com) is a Brooklyn-based artist influenced by her family’s oral histories. Maia is a recipient of the Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Program Grant, Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant, NYFA Painting Fellowship, Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Award, and the Astraea Visual Arts Fund Award.