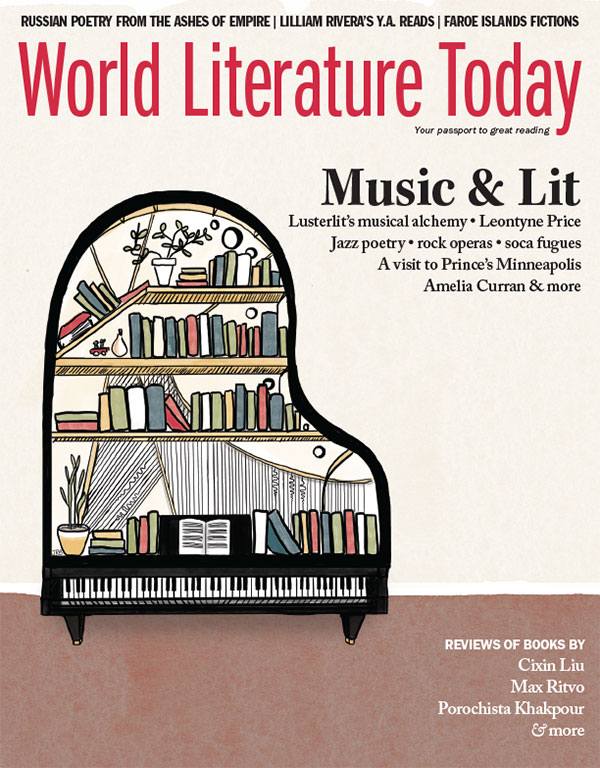

Amelia Curran: “I Am the Song”

Is Canadian singer-songwriter Amelia Curran a mix of Leonard Cohen and Patsy Cline? A juggler of Robert Frost’s poems? Andrew DuBois considers her art and influence from a shared landscape in Newfoundland.

When you’ve flown as far east as you can fly over North America, the last place to land is St. John’s, Newfoundland. Some people head straight from the airport to the lighthouse at Cape Spear, which is the continent’s true most eastern point; others hike or drive up Signal Hill, to stand where Marconi stood to receive the first transatlantic wireless message, sometimes texting from the top; still others head toward Jellybean Row, to walk a stone’s throw from St. John’s Harbor, sauntering among the bright and whimsical saltbox shops and row houses of Duckworth Street and its steep, sloping environs.

Count me among the latter. It is not just that Duckworth satisfies the architectural sweet tooth—though it is impossible not to light up at the purples, yellows, oranges, ochres, reds, pinks, greens, and blues that shine like a smile through even the foggiest harbor days. It’s because that’s where you find Fred’s Records; and Fred’s Records is where you go to get your Newfoundland music fix. No neophyte pop-up shop of the vinyl renaissance variety, the venerable Fred’s has instead been around for some forty-five years. The space is full but not cramped, the staff resolutely unsnarky, and the recommendations astute. The store doesn’t only sell local music, but it seems to sell all of it.

Drawn to its title and cover, a curious observer decides to try They Promised You Mercy. When he gets it home and puts it in his player, where it will stay unreplaced for weeks, he discovers that rarest of things: the perfect album.

A curious observer can hardly help notice, placed at the front of the store, several albums by an artist named Amelia Curran, festooned with enthusiastic descriptions written by the staff in block letters and colorful pen. Curran, a St. John’s native, is a songwriter-singer-guitarist who over the course of five albums—War Brides (2006/2008), Hunter, Hunter (2009), Spectators (2012), They Promised You Mercy (2014), and Watershed (2017)—has made a name not only in this island province but elsewhere in the country and beyond. (Her second album, for instance, won the prize for Best Roots and Traditional Album at the JUNO Awards, which is Canada’s Grammys.) Drawn to its title and cover, a curious observer decides to try They Promised You Mercy. When he gets it home and puts it in his player, where it will stay unreplaced for weeks, he discovers that rarest of things: the perfect album. Later on, after further observation of her work, he will find it to be of a piece with the entire oeuvre.

AMELIA CURRAN IS A TUMBLE of paradoxes and ironies. She articulates her lyrics with total clarity, yet the persona she conveys floats in and out of distinctness; her songs are relentlessly first-person, yet there are so many self-definitions that some are self-canceled and none coalesce; her music sounds old but sounds new; she’s smack in your face but she hides. Her first words on War Brides, Curran’s introduction to the world, come from a song called “Scattered and Small” and are strangely already posthumous: “I was so alive, I can only look back.” This, of all things, at the start, words from the talking dead: beginnings containing their endings, nows resurrecting their thens. Time—as both fact and as concept—is truly of the essence for Curran, and, respecting its mystery, she doesn’t quite know what to make of it—other than art.

In her hands that turns out to be plenty. The second song in her corpus is called “Furious Curve,” and it’s a curious swerve indeed, not in its sound but in its sense of time. “Oh the future is flying too fast for the furious curve,” she begins, speaking truly for us all, before ending, “What if someone subtracts from the sum of all fears?” At first I took that to mean: what if someone comes along who takes away from our fears, a benevolent arrival. (Lord knows we could use it.) Later I figured it might mean: what if a person, someone, anyone, in the face of all these fears, shrinks, subtracts, gets scattered and small?

“Time was the telltale factor for all of our fate.” This, from a later song called “You’ve Changed,” feels as old as alliterative verse, as fresh as bouncing syllables bouncing still. Curran’s diction is spare, her poetics abstract and metaphorical, her rhetoric often anaphoric, her lines almost always end-stopped albeit with occasional rhythmic elisions of enjambment where the line just keeps on going. It is not devoid of the mystic. (She believes in “Devils,” as a song of that title attests.) Hers is a poetry of archetypes and figures, not elaborate images or developed conceits. Her lines have the aphorist’s balance, the residual impact. You circle around them like a koan: “Time was a storybook, time was a thief.” Even time can be turned by Curran into the past tense. But when you have reverence for the past, nostalgia for the present, and fear of the future, you are experiencing a certain kind of totality of time.

Curran’s is a poetry of archetypes and figures, not elaborate images or developed conceits. Her lines have the aphorist’s balance, the residual impact. You circle around them like a koan.

Her second album, Hunter, Hunter (a play on “hunter-gatherer”), starts with a song saying au revoir as hello (“Bye, Bye Montreal”: “If you’re in town you’ll look me up / We’ll dance the days into the cups”) and ends with a song called “Last Call.” The latter sounds like a hazy vision of an actual night out on George Street, a classic port street, which is sort of a St. John’s version of Beale Street, but with way less blues and barbecue, much more ocean air. Willie Nelson once wrote that “the night life ain’t no good life, but it’s my life,” and given the proliferation of boozy evenings and painful mornings in her lyrics, Curran would likely concur:

Those red-faced prophets, bartender, and me

They’re dancing in riddles on top of dead dreams

I kissed a sailor, said he was the sea

But he never knew it from me

Last call

Time is an invalid inside us all

Like the pub scene in The Waste Land (“Hurry up please, it’s time”), the end of the night is the end of the line. In the same album’s “Tiny Glass Houses,“ Curran imagines an opposite path, a Benjamin Button-esque dream of reversal (with just a touch of Auden): “Drink ’til you’re sleeping, I love you that way / Like we are all babies, all our beds are unmade.” Silently and sweetly slovenly, instead of dumb, dirty, and drunk—the melancholy barfly’s dream.

Amelia Curran performing at The Ship Pub in Newfoundland. Photo: Zach Bonnell

The term “singer-songwriter” conjures a folkie sitting on a wooden stool on a bare stage, and although I’m sure she can play that and any other way, Curran as a maker of music is sparely (yet quietly, slyly, lushly) textured.

Red-faced and face-down is not the only way to depict this persona, however. That version is too passive for Curran to rest on. She kicks off her wonderful list-song of self-definition, “I Am the Night” (from They Promised You Mercy), by owning the decision to stay out till all hours: “I am the queen of the closing bar.” She is a musician, after all. She is an incredible number of things. Reading through Relics and Tunes: The Songs of Amelia Curran, published last year by Newfoundland’s Breakwater Books, the “I am” construction yields up numerous things that Curran is:

A factory

A clarity

A memory (1978, to be exact)

A vision

The matador coaxing your love to my core

The shadow that heightens the light

A wild abandoned ray of heat

A lover’s enemy

Just a Tuesday in a world of Friday nights

A fortune of fever and lust

The wrecking ball

Just a road

And then there is “I Am the Night” itself, with its repetition-powered insistence of being:

I am the gravity that holds you down

I am the jewel in the thorny crown

I am the furthest from the madding crowd

I am the seventh of the seven pounds

I am the tremor in the nightmare deep

I am the ceiling on your lifelong dreams

I am the medicine that keeps you clean

I am the fortune in the telling scheme

And yet this is not clearly just Curran herself speaking, of course, for the song is an apostrophe and it is Night herself who is speaking. This vacillation between the presence of the singer through her voice and her absenting herself in her figures makes for a foggy but brisk-winded vitalism in practically every verse.

THE TERM “SINGER-SONGWRITER” conjures a folkie sitting on a wooden stool on a bare stage, and although I’m sure she can play that and any other way, Curran as a maker of music is sparely (yet quietly, slyly, lushly) textured. She folds sounds up, kneads them. A cursory accounting of instruments heard on her albums includes acoustic and electric guitar, electric and upright bass, drums, percussion, cello, mandolin, harmonica, accordion, trombone, clarinet, banjo, bouzouki, trumpet, flügelhorn, French horn, tenor sax, lap steel guitar, violins and violas, dobro, piano, Hammond organ, and a good deal of vocal harmonizing. This paints a picture of Curran as a bandleader as much as a solo act. She can go up- or down-tempo and lose nothing in between. She edges up against the sweetness of good pop, on one hand, and something rusty and clangy and rough, on the other, without ever really veering too far either way.

As with most original artists, inside their originality you can hear echoes of their stellar predecessors. To use an overextended and hipsterized word, the true original is a great “curator” of her own influences. One critic called Curran a mix of Leonard Cohen and Patsy Cline, and while it wouldn’t be my first choice, you could well do worse. When she writes, “And you won’t find me / Oh no, you won’t find me” or “And you won’t see me” or “And you won’t catch me,” one recalls the “He’s Not Here” persona of Dylan; or the hiding behind a mask of Joni Mitchell on Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter; or then again, one hears strains of the great country songsmith Cindy Walker, who proclaimed that “You don’t know me.” The maritime plaintiveness of the Newfoundland legend Ron Hynes comes through in her sadder laments. The chorus to “Fables & Troubles” could have come from Liz Phair’s Whip-Smart. When Curran sings that “God’s no rebel, he’s a handyman,” the spectral Judee Sill is there, echoing back that “Jesus was a cross maker.” Several lyrics sound like a juggling of the poems of Robert Frost: “I have made a promise that I have promised to keep,” “There’s no untaken road when nothing stays for long,” “In brazen secret paradise / A carousel of fire and ice.”

In the introduction to her collection of lyrics, there is a brief discussion regarding the difference between poetry and lyrics; like most such discussions, this one is circular and unsatisfying. Yet Shannon Webb-Campbell, a friend of Curran’s who pens it, puts it nicely when she writes that Curran “illustrate[s] how words are married to the melody. Their relationship relies on vows made to one another.” One can agree with Curran up to a point when she says, “Lyrics must have music to communicate. Poems must have a page.” Yet as someone who reads roughly a hundred new books of poetry every year and who has ingested much moribund verse in the name of historical scholarship, I can say without exaggeration that Curran’s lyrics on the page are as successful as 75 percent of all that stuff in print. Naturally, having those lyrics set to music, played expertly, and having those words sung beautifully by their own composer raises that percentage by far.

Fred’s Records on Duckworth Street, “where you go to get your Newfoundland music fix.” Photo: Kevin Williams

“THEIR RELATIONSHIP RELIES ON vows made to one another.” As coincidence would have it, not long after I had procured Curran’s War Brides, I was up at a place called Grates Cove. There are lots of rock walls there—they cover 150 acres—and if you drive a little way from there to Red Head Cove, you can get your best view of the birds on Baccalieu Island—petrels and puffins and kittiwakes and gannets and murres. My trips to Grates Cove tend to involve stopping at an inn, studio, and restaurant there run by a friendly couple named Courtney and Terrence. Terrence is from around the cove, and Courtney is from Louisiana, and they met teaching English in South Korea. Thus, their food is an unexpected mixture of Creole, Korean, and local Newfoundland fare. I’m from north Alabama and have retained a good deal of my accent. Eating my jeon and snow crab étouffée, I overheard two couples talking to one another. The one couple had accents like mine but with added syrup, so (very much out of character) I asked if they might be from Alabama or Georgia.

They were from Georgia, it turned out, and we asked each other how we’d come to be where we had come. My story was boring: I was living in Carbonear because I liked it there. Theirs contained more oomph. The wife in the couple was the daughter of a woman who had been a “war bride” from St. John’s. Her mother, from a well-to-do city family—but not yet a Canadian family, as Newfoundland was not yet part of Canada—married an American serviceman who was stationed for a while on the island during World War II. After the war was over, she resettled in rural southern Georgia, following her husband back to his native home. The daughter, now in her seventies, said it was a big adjustment for her mother, from electric lights and indoor plumbing back to candles and outhouses.

In “All the Ladies,” Curran sings, “It’s the same old story that I’ve heard ten times before / You’re sending your love to war [. . .] And all the war brides sing their soldiers’ songs / The night is short, dear, but their love is long.” I had always thought of the painful romance of longing, the worried wife left behind, the constant fear of the arrival of the fateful telegram. I had never considered what happened when that telegram thankfully never came, when a man essentially new to you returned, alive but not likely unscathed, to begin to dictate in part how your life would now be. On her newest album, Watershed, she says, “Time is only tireless, it cannot rewrite / Love is only heartstrings that you will not untie / You have got each other.” To me she’s the soldier and the wife, the country and the city, the present and the past—the melancholy, romantic past; the melancholy, realistic present. You can see her smiling and snapping her fingers: “You know I love the subtle silence.” Then she whips her bandmates into gear.

Toronto, Ontario