Summer with Halla

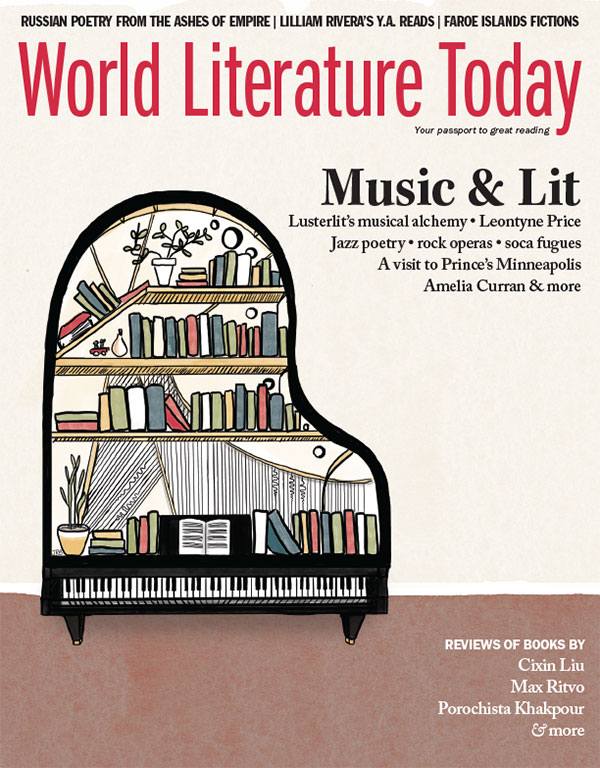

A woman’s complicated relationships with her garden, her teenage daughter, and an irrepressible, mysterious young neighbor converge in this story from the Faroe Islands.

I stand in the doorway of my daughter’s room. Jerusalem’s destruction. The only difference is, eventually the city was rebuilt. I feel myself growing angry, but fortunately I know exactly what will help. I shut the door, toss a sweater around my shoulders, go out into the garden, and—poof!—all unpleasant thoughts are gone.

Out here I walk around doing all the garden tasks you do if you’ve been bitten by the garden bug. If you haven’t been bitten, you have no idea what I’m talking about.

One of my friends likes to say: “Okay, seriously now! What in the world do you do in your garden at all hours? My God! I have a garden, too, but once I’ve cut the grass every couple of weeks, there’s just not really that much to do.”

Patiently, I try to explain to my friend that you’re never really done in a garden, but I can tell she thinks I’m a bit strange.

Today, though, is a beautiful summer day, and I have no idea I’m about to meet Halla and that she’ll ensure this summer remains unforgettable. I pause to stroke my tree. There are quite a few trees in the garden, but this tree is something special. It arrived as a tiny seed in the belly of a bird and settled down in my garden, as if to say: “This is my home.”

I saw it one day when I was down on all fours pulling weeds. My hand was already hanging in the air, poised to yank the little green shoot and toss it onto the heap when something caught my eye. There was something different about it, that little plant. It was a festive moment. A little tree. Two centimeters tall with three tiny leaves. I placed a small, protective fence around it and cared for it and it grew just beautifully. I remember the first time I saw a rock pipit perch on it. Though the little branch could scarcely bear its weight, the pipit sat there a good long while and swayed. Now the tree is so big that birds can build nests in it.

Patiently, I try to explain to my friend that you’re never really done in a garden, but I can tell she thinks I’m a bit strange.

And now here I am, standing there and stroking it and talking to it.

“Mom, you’re completely nuts.” My daughter always shakes her head at me, the way I go around and baby-talk all the growing things. But I can’t stop. To me it’s a wonder, each time something sprouts and grows.

I watch how everything thrives beneath my hand, and I reflect on how vulnerable it all is. Unable to escape, bound to the place it stands—there it is, its whole life. Of course, seeds can be released; they fly out into the world and plant themselves elsewhere. Like my little tree here. Plants and trees can scatter their offspring, but they themselves never slip their roots.

Perhaps that’s why I like trees so well, because they’re so still. And it’s not that they just stand still. They don’t talk back like children but stand there and patiently listen to all I tell them, and then they whisper in the wind, as if to say: “Oh you, oh you. That’s priceless.” Their sighing gives me a feeling of such peace. It whisks aside the tedium, and I can feel myself completely in harmony with all this green.

Every time something new happens in my garden, I bring my daughter out to view the marvel.

“When I’m grown, I’m never having a garden. No way I’m dragging my kids outside,” she says.

Still, her words lack bite and she continues to tease me: “What was that plant called again? Ragged robin?”

As I turn away with an expression that clearly says I’m shocked at how little she’s picked up, my daughter just stands there and laughs at me.

But back to that beautiful summer day. Out in the garden, I sing softly to myself. My daughter has a rabbit: black and white and extremely well loved. When I’m outside, I take her out of the hutch and she hops along at my heels. When I sit to rest, the rabbit settles at my feet, lays her ears back, and dozes, enjoying the sun’s heat.

As we’re thus relaxing, I sense that someone is looking at me. I turn and find a small girl standing there outside the fence.

“Hey,” she says. “Can I come in?”

I tell her to come in already. I’ve always liked talking to small children.

“Can I help you out?” she asks.

“Sure,” I say, handing her a small pail. I tell her to collect pebbles in it but to be careful and not to pull up any plants inadvertently.

“Here are some rocks,” she says, “little and big ones. Which should I pick up? Should I also pick up the really tiny ones?”

I show her which size rocks to put into the pail and she chatters on.

“On no, look at this one, how tiny it is. It’s just as tiny as a booger.

“A what?” I ask.

“A booger, don’t you see?” She wasn’t smiling, so I decide to let it be.

“Yes, it is small,” I say. Then: “What’s your name.”

“My name’s Halla and I’m five years old. My mom’s name is Marita. I have four papas,” she says in a rather solemn voice, putting rocks in the pail. She can’t really pronounce the letter r, so it comes out fía pápaj. “They’re all nice, but Hannis is the nicest one of all, since he always gives me money.”

Now I’m curious. “Where do you live?” I ask.

“Up there.” She points to a house a little ways off.

“Do you have any siblings?”

“Yeah, a little sister, she can’t do anything, and a big brother.”

“How old is he?” I ask.

“Don’t know,” she says, wiping her nose with a grimy hand. “But he’s big.” She pauses a moment, then her small face, which is also covered in dirt, lights up. “He’s as big as a door.”

Now she catches sight of the rabbit, who’s been lying there and sunning itself. She drops the pail and the rocks roll in all directions.

“What’s that?”

“That’s a rabbit. He’s called Mubbi,” I say. “Don’t you have any pets?”

“No,” she says, staring at the rabbit. “We don’t have any pets. Do you think I can take him home? I can bring him back tomorrow or another day.”

“No,” I say. “Not this time. She lives in that hutch over there and I think that’s best.”

“How do you know?” Halla asks.

I see an endless dialogue full of questions confronting me.

“Because one time she told me.”

“Oh?” Halla accepts the answer. I feel slightly bad about it, but what can you do?

I’m looking up at the house where Halla lives. In the yard I see a big, brown German shepherd.

“Halla, didn’t you say that you don’t have any pets?”

“Yeah, we don’t have any pets,” she says, looking at the rabbit.

“What’s that?” I ask, pointing. She glances up.

“What? Oh, he’s not a pet. His name is Prins.”

"WELL, WE'VE BEEN SO productive, we’ll need something to drink,” I say.

“Yeah,” Halla replies and we go inside.

During our break, Halla’s gift of gab doesn’t leave her for an instant. She hardly has time to eat. Nor does she seem in any hurry to go home, but since it’s getting a little late I tell her it’s time to leave.

“Why?” asks Halla. Turns out, this will be a heavily reoccurring question.

With difficulty, I get her out the door and tell her to run along home.

When my daughter returns, I tell her about Halla. She’s convinced that since I’ve been so welcoming, Halla is bound to show up again.

THE NEXT MORNING there’s a knock on the door. It’s not much past eight.

“Hey,” Halla says. “I’m coming to visit you. You got anything good?”

I give her a Sun Lolly and some chewing gum, and after she’s talked for about three hours, I tell her to go play outside.

“Why?”

“The weather’s too nice to stay indoors.”

“You’re indoors,” Halla says.

I give her a Sun Lolly and some chewing gum, and after she’s talked for about three hours, I tell her to go play outside.

I try to explain that I need to clean house and work on the computer. She doesn’t seem convinced, and it’s a real struggle before I’ve finally pushed her out the door and dried the sweat from my forehead.

The next day she’s there again and the day after that. She says she’s coming to visit and makes herself comfortable in her chair, as she calls it.

Usually, my mornings are so peaceful. Either I listen to the radio while I do what needs doing or I put on some music I like. But now, since Halla is here, peace is a thing of the past. She talks and talks, so that it’s about to drive me insane.

One time I interrupt her: “Halla. Why aren’t you at home with your family?”

“Huh? Because no one’s there, obviously. Besides, Prins is mean. You always clean. We never clean. I got to sleep with mama last night. Mom says sometimes it’s good without a man. I think so, too. And you know what else? Prins woke me up. He barked so horribly. We forgot to let him in. That’s why I didn’t get any sleep.”

“No, now it’s getting out of hand,” I tell my daughter, but she just laughs at me.

“Nonsense, mom. Weren’t you the one saying how much you liked little kids? You can stand a little visit.”

But the next day, there Halla is again. When I open the door, she’s standing there with three other small girls. One of them is in her underpants and blue with cold.

“I’m coming to visit you and I brought them along. We played that we were sunbathing and we hid her clothes,” Halla says, smiling and pointing at the little blue-frozen girl, who also laughs with glinting teeth.

“No, now what’s this?” I scold them. “You just turn right back around and find this little one’s clothes and get her dressed.”

“Why?” asks Halla, and I threaten them with pneumonia and the hospital.

“Okay,” Halla says, “but then we’ll come back.”

I shut the door and lock it. It’s the first time I’ve resorted to that. I don’t usually lock up completely.

But it won’t be the last time. Sometimes I pretend I’m not home, but that doesn’t keep Halla out. Closed doors don’t dissuade her; she just goes looking. She runs around the house peeking in every window she can reach, not to mention the balcony door, which is often left open and unlocked, and which Halla can squeeze through.

Sometimes I pretend I’m not home, but that doesn’t keep Halla out. Closed doors don’t dissuade her; she just goes looking.

One day she drags a big crate over to a window so she can look through it. When she sees me, she waves happily.

“I knew you were in there! Open up! I’ve come to visit!”

When I tell my daughter about this later, she frowns at me.

“I’d never have believed that of you, Mom. That you’d ever be mean enough to lock her out. You should be ashamed.”

And I was a bit ashamed, but the truth is, these days nothing I do pleases my daughter. My role as the world’s best mom has been temporarily put on hold.

Still, I’m forced to smile as I observe that, after meeting Halla a few times, my daughter’s also prone to flee.

Her room is in the basement and she’s at the age where she wants to sleep constantly. Unfortunately, she keeps waking up with Halla standing over her and staring, or standing there painting her nails, or rooting around in the precious jewelry box.

“Hey,” says Halla. “Finally, you’re up. I’ve come to visit. Why do you sleep when everyone else is awake? Is all this yours? What’s that? Can it be mine?” And then Halla starts touching everything.

“Go visit my mom,” my daughter says, shoving Halla out the door and locking it. Halla resists and asks why but is ultimately forced to obey.

The climax occurs one day as my daughter and I are talking peacefully in the kitchen. She’s just come home from school. Walking into the kitchen, she embraced me, like she always used to do, and gave me a hug.

I grew warm inside and hugged her back and didn’t have the heart to tell her to clean her room like I’d planned to do when she came home. She’s been so distant lately. Hard to reach. I tell myself she’s going through a change.

As we sit there, we hear Halla calling.

“Hey, I’m coming to visit!”

We stare at each other. Jump up, run to the attic, and lock ourselves in the bathroom. We hold our breath and listen and hear Halla on the stairs. First, she runs down to the basement. Then to the second floor.

“No one there,” we hear her say. Then she heads for the attic. She tries all the rooms until she reaches the locked door.

“Here you are!” she exclaims gleefully.

We sit and hold each other giggling, until I look in the mirror and think: “Dear Lord, what’s going on here? You’re a grown woman in your own house and here you are, crouched like a thief, hiding from a little girl.”

I give up, try to look stern, and open the door.

Outside stands a smiling Halla with her arms full of flowers, which have obviously been collected from someone’s garden.

“These are for you,” she says, thrusting the flowers into my arms. A chill runs through me and I start imagining all my carefully tended flowers and all gardens in general lying in desolation for the summer.

Before I can bring myself to speak, Halla says: “I took all the most beautiful flowers I found. I took them from the garden next to yours since that day you said I couldn’t take flowers from yours.”

I want to cry and laugh. What in the world am I going to tell the neighbor?

I try to explain to Halla that she can’t take flowers from other people’s gardens either.

“Yes, but they were for you,” she replies and looks at me with those innocent eyes. It doesn’t make it any easier to tell her what I’d determined to say while in the bathroom.

“Halla, enough. When you come to visit, you have to knock, and if no one answers, you should leave and go home.”

“Yeah, but if you’re here, why?” asks Halla.

“Because, that’s just the way it is,” I say firmly.

She agrees and we all three decide to get something to drink.

Halla watches me while she sips hot tea from

her mug.

“Do you have a straw?”

I get up and hand her one. She drinks and prattles about this and that and swings her legs while she watches me. Her face is as serious and grimy as usual, and her hair is one big tangled knot. She scratches her neck and I think to myself that it would be a nice little paradise in which to settle if you were a six-legged something that liked to suck blood.

I have the urge to fill the bath, plop Halla down, and scrub her clean.

“Who can her mother be?” I wonder. “No one knows a thing about them.”

I scratch my own head but am interrupted by Halla, who has stopped talking and is staring at me instead.

“Are you ever drunk?” she asks.

My daughter perks up and I can tell she finds the question amusing. “Yeah, what do you say to that?” she murmurs.

I look right into Halla’s little face and say: “No. Never.”

Summer whispers call dreams before the senses. Good, true happenings, which are receding, and those I just dreamed of and have tucked away like a well-tended ember.

When I’ve finally gotten Halla out, I walk the heavy path to the neighbor’s carrying the flowers.

After this things get a little better. The knocking is constant, but since my conscience twinges every time I hear it, I usually let Halla in.

NOW SUMMER IS OVER. Some things still persist. The marigolds are such a bright yellow and the roses haven’t surrendered yet.

When I’m out here in the garden, I listen to how the wind rustles the tree crowns. The sound of fall. Not the whisper of fresh, lush, idle summer leaves, but the murmur of dry, brittle, delicate leaves trying to hold fast as long as they can. I feel a kinship with them as I stand here. Summer whispers call dreams before the senses. Good, true happenings, which are receding, and those I just dreamed of and have tucked away like a well-tended ember.

Fall sounds, on the other hand, induce reality to lay a hand upon my shoulder. In admonishment. Still, it can’t be denied that here, too, is a bit of gentleness. Fall sounds bring a crooked smile to my lips as I go around and clear away summer.

A leaf loses its grip and slowly falls, executes a turn, and settles soundlessly at my feet.

Halla disappeared as suddenly as she came. Some say that they moved. Others that they were evicted. And as I now sit in my peaceful kitchen with my coffee, I look over at the chair Halla used to fill. I picture the grimy, chattering little face and feel an odd yearning.

Something like the emotion when you know you’re pregnant and neither wanted it nor could handle it just then. Then your period comes and there’s relief but at the same time an unexpected twinge of sorrow.

Such a feeling.

Translation from the Faroese