The Suitcase of Saba’s Last Journey

A polyhedron of blond leather. Thirty-two by seventeen by twelve. Solid handle, brass hooks, wide belt, reinforced external corners, hand-sewn. Inside, top, a striped black-and-white lining gathers over the elastic of two flat pockets; below, the area intended to contain clothes is crossed by strips of light leather with their buckles and loops.

Which routes did Saba’s suitcase travel before it found me, in Rome? Is it the same suitcase that accompanied him as he moodily wandered through Italy? The honest Poet, forced to earn his daily bread in the hometowns of various papers and publishers and to stop for longer and longer periods of time in order to cure uncomfortable troubles.

What is now my suitcase might have followed him to Gorizia, last of his destinations.

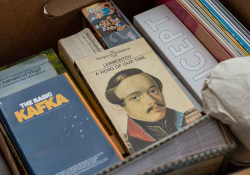

A few clothes, photos of Lina and Linuccia with Carlo Levi, business cards, manuscripts, books.

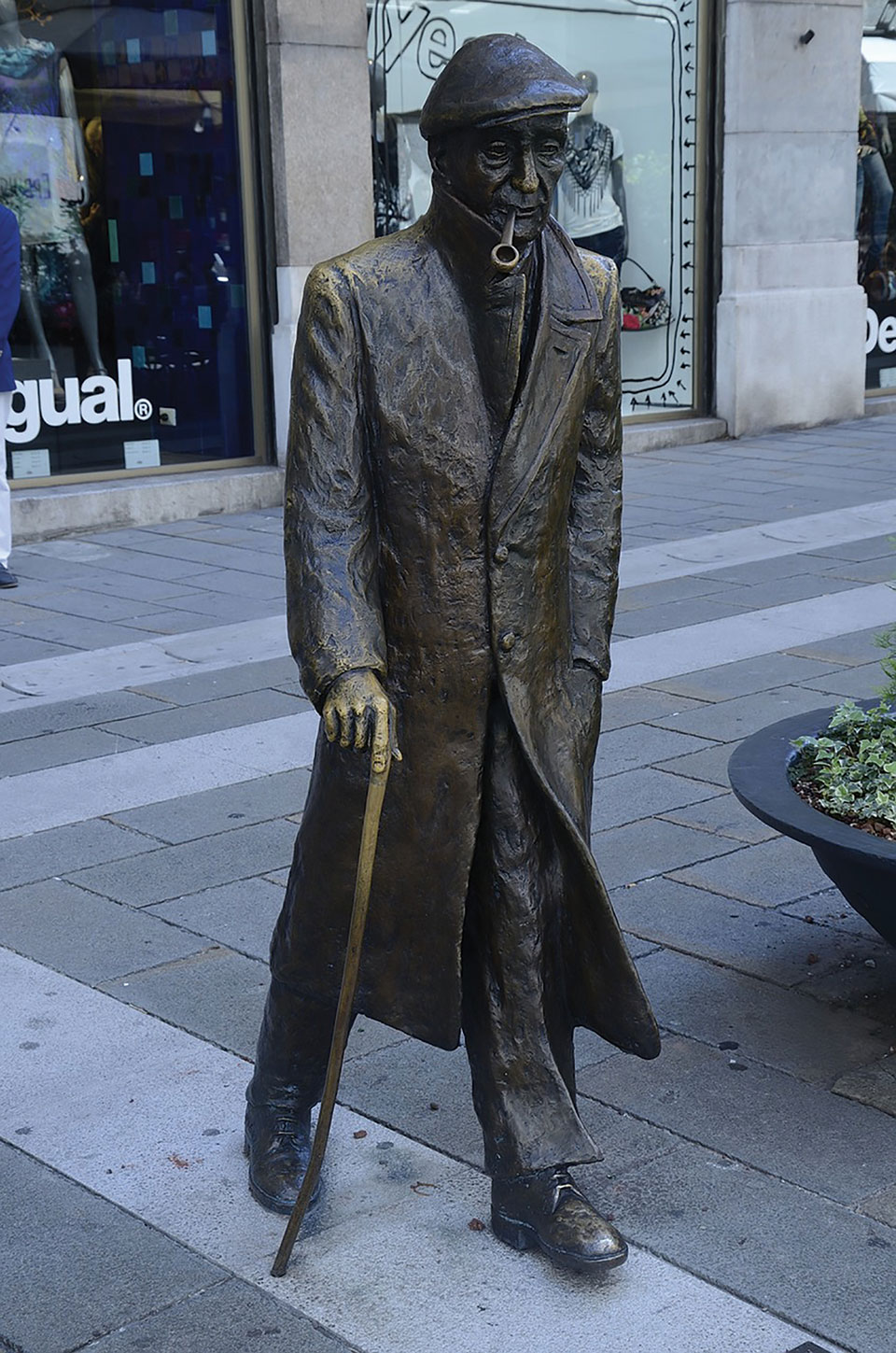

If Nino Spagnoli had seen it—the suitcase—or imagined it, he could have added it to the bronze of Saba that the town of Trieste commissioned of him in 2004. Cane in hand, coat billowing in the wind, the Poet seems to be at peace as he walks the streets. Add the case to the cane: now he’s urged to leave “the dark cave” by an early departure, at dawn.

The bronze statue is simple and spare, as suits Spagnoli’s quiet fashion. Three of his creatures stroll around town: Saba, Svevo, and Joyce, following the early two thousands trend that abhors pedestals and asks heroes to alight from their mounts. At ground level, in the street, together with urban pedestrians, things among things, folks among folks, the contrapasso makes them—at least their effigies—lovable and amenable to being hugged by visitors for a souvenir snapshot. Elsewhere—with the same sad irony—other lonely statues placed at ground level (a trend, as we said) mutely gather villagers’ jokes. Sciascia hastily walks away in Racalmuto, a few steps from the bar; Germi sits on a bench of Sciacca, forever atoning for having there seduced and abandoned young Stefania Sandrelli. And so forth.

The Italy evoked by Saba’s suitcase is extinct. The morality—“moral fact,” as Mario Mafai puts it—of the men who have made the suitcase is now archaeology. Objects built to last, bought once and for good, alien to all concept of low cost. Skills of laborious craftsmen exchanged for daily bread. It’s a luxury, this thick leather case, if compared to the cardboard luggage reserved to the lower class. Not the trunks of the Vate, progressively numbered by the size and initialized in gold leaf—but the suitcase of the Poet/merchant who loved old books “like pimps love beautiful women: in order to sell them,” to grant himself and family at least some viable income.

Among piles of excess merchandise, in the back of the shop where only a few privileged were admitted, my suitcase was found by the quick eye of an aficionado hunting rare editions; volumes from Trieste’s, Gorizia’s, Vienna’s, and Berlin’s estate sales that during forty years made the Libreria Antiquaria Umberto Saba the most coveted joint for collectors and bibliophiles, bibliomanes and Mitteleuropa’s scholars.

I have made a strange pact with the friend who thirty years ago gave me this suitcase: I have promised I’d never reveal his name. I will not. The suitcase was there and he saw it. The only one to understand what it was, he asked Carletto Cerne about it, now managing the library alone.

“Yes, it comes from Saba’s home . . . he had just arrived from Gorizia, his last journey. That day, I filled it with books and papers I needed to bring to the store, and now here it is. Take it, please. I’m happy for you to have it, and you know what? I’ll fill it with the volumes you have bought and I’ll send it to your hotel. Those books! . . . Spadolini fancied bringing them to Florence! But I had put them aside for you, and I have kept my promise. They are fresh from a Viennese estate. They still smell of Weimar.”

Trieste, Gorizia, Vienna, Florence, Rome. Umberto Saba, Lina, Linuccia, Carlo Levi, Carlo Cerne, Spadolini. Is that true? Perhaps not entirely. But we are talking about a poet’s suitcase. Open it, and moonlight, wishes, dreams fly away. Music. And illusions.

Translation from the Italian