There Is Also This Civil War Inside of Me: A Conversation with Zisis Ainalis

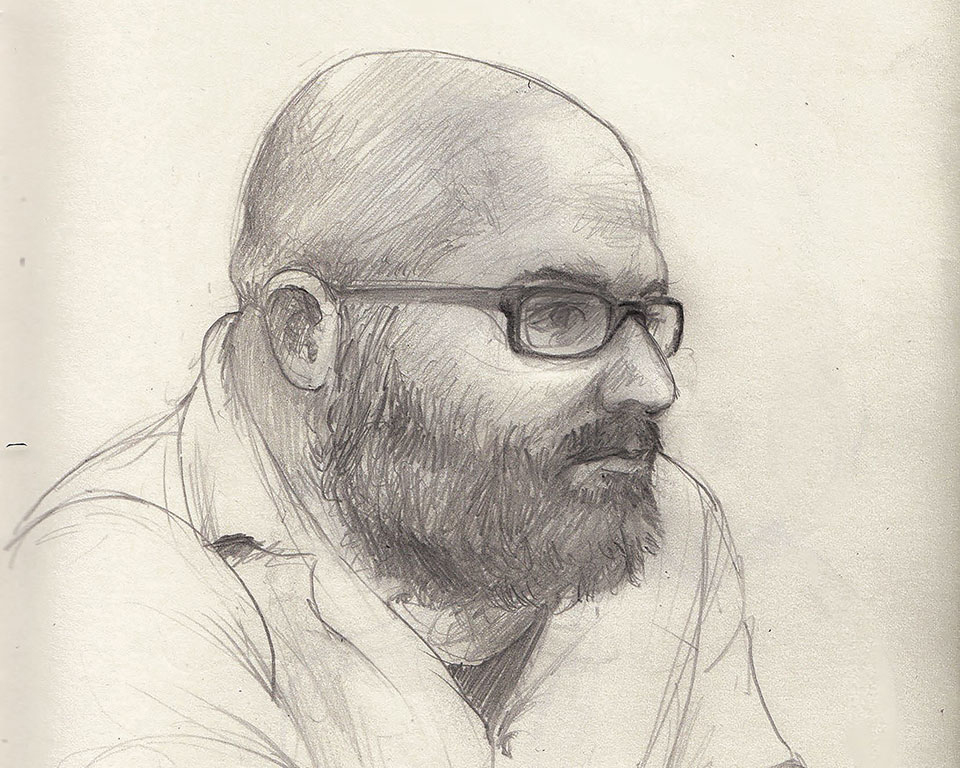

Zisis D. Ainalis was born in Athens in 1982. A poet, translator, and essayist, his work has been translated into English, French, Italian, and Portuguese. He lives and works in Mytilini (Lesbos), where he is a member of the editorial group that publishes the literary magazine North-Northeast. He has published seven books of poetry: Electrography (2006), Fragments (2008), Michalis Tatsis—Holding up the Stake with the Hands (2011), Sheba’s Silence (2011), Mythology (2013), Desert Tales (2017), and Desert Monody (2019).

Adam Goldwyn: In some ways, Desert Monody, your 2019 verse collection, seems to be a continuation of your poetic trajectory. Like Sheba’s Silence, which uses the story of Solomon as a symbol for discussing other more modern problems, this volume also reaches back to the Bible, particularly the exile from Eden and the stories of early Christian desert ascetics. But it also marks a big shift—less political, less overtly concerned with modernity than, for instance, Electrography, and, of course, also in prose. What was the genesis of this volume, and how do you see it fit with what you’ve done before?

My poetry is—it has always been—about my time, or, better, it is the reflection of a consciousness of my time.

Zisis Ainalis: The genesis of Desert Monody lies in a decisive fact of my life: the birth of my first daughter, and it treats in a more or less hidden manner but one theme—paternity. The alterations in one’s consciousness that the birth of a child brings forward, the individual and collective meaning of paternity, and the difficult psychological proceedings that follow—these are the subjects that I wanted to treat. I think that this is a topic somehow neglected in modern literature.

Zisis Ainalis: The genesis of Desert Monody lies in a decisive fact of my life: the birth of my first daughter, and it treats in a more or less hidden manner but one theme—paternity. The alterations in one’s consciousness that the birth of a child brings forward, the individual and collective meaning of paternity, and the difficult psychological proceedings that follow—these are the subjects that I wanted to treat. I think that this is a topic somehow neglected in modern literature.

From this point of view, I dare say that this volume is radically different from my previous works precisely because of its subject, hitherto unknown in my poetry. However, poetically there is a link connecting all my works between them. I like to think of my volumes of poetry as a kind of autobiography in process. But my poetry is not about me, if that makes any sense. My poetry is—it has always been—about my time, or, better, it is the reflection of a consciousness of my time. Thus, the political dimension of my work. Generally speaking, more and more, I head toward a rehabilitation of the meaning.

Goldwyn: Let’s talk about the political dimension of your work. In one of the poems that will accompany this interview, you speak of “this civil war inside of me.” How do you see your politics in your poetry, and do you see yourself in the tradition of Greek political poets like Yiannis Ritsos, the left-wing Resistance fighter during World War II, or George Seferis, who was such a vocal opponent of the junta? What is the role of poetry in politics?

Ainalis: This is a rather complex question that I can’t possibly answer here. However, I believe that, in a sense, all art is political, in an Aristotelian meaning of the word (and I remember here Arendt’s exquisite remarks on polis and society). As far as I am concerned, I have a strong propensity for history. History and literature are inextricably connected in my mind. I think that the political element in my poetry comes either from the presence of history in my work or the way that I treat the present through the spectacles of the past. Take Cavafy, for example. His poems aren’t overtly political. On a first reading they seem to be mainly historical. However, his use of history is what gives his poems a political dimension. But I don’t want to be misunderstood: I am not talking here about some kind of nostalgia of the past. I am talking more about a way of attempting to comprehend the present through the experiences—literary as well—of humanity’s past. And as long as there is a public realm in humanity’s institutionalized life, this will always be a political procedure.

Nevertheless, the role of poetry in modern-day politics is nonexistent, in the sense that poetry, of course, doesn’t affect—despite the ludicrous political ambitions of some poets—the political agenda. However, that doesn’t mean that poetry shouldn’t have or doesn’t have a political perspective, usually wider than the day-to-day politics. As a reader, I like this kind of political reflection, which we can find in much of the literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Can you possibly think of more intriguing political texts than the epilogue of Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Dostoyevsky’s Demons? Thoreau’s Journals contain a great amount of political reflection. Kafka, T. S. Eliot, and Camus are essentially political authors. You see, I am not talking necessarily about politically engaged authors. Still, I am heavily influenced by the political literature of the Greek postwar generation. The works of Alexandrou, Tsirkas, Hatzis, Alexandropoulos, Katsaros, Anagnostakis, Livaditis, and Leontaris accompanied me throughout my adult life.

Goldwyn: In small font at the end of Desert Monody, you write that the volume was composed in Patras, Paris, and Chios. Reading in between the lines here, what is missing is Athens, the center of Greek literature and politics. Can we see any general trends in Greek poetry between islanders, expatriates, and Athenians? And can you, having been each of them at different parts of your life, speak to how these locations influence your poetry?

Ainalis: I have always been a stranger no matter where I was living. I was born and raised in Athens, but I haven’t lived there since 2000. Athens is always a part of myself and a part of my poetry as well, in a sense. As is Paris. Two great metropolises of modern Europe. However, this feeling of strangeness, of not belonging somewhere, is following me wherever I’ve lived. I have been living all my adult life as an expatriate, regardless of whether I was living somewhere in Greece or not. But this is probably a personal feeling or even the malaise of modern human beings: the “uprootedness,” as Simone Weil put it some three generations ago.

To answer the question, I don’t feel that there are some general trends in Greek poetry between islanders, expatriates, and Athenians. I think that globalization absorbs a great deal of the local differences. The Greek poets of my age, people in their forties, could have been active all over Greece—or abroad. And they are. You can find poetic circles in many Greek cities: Thessaloniki, Drama, Larissa, Patras, etc., as well as poets living permanently abroad. The strictly speaking “local tradition” seems to influence modern Greek poets less than, let’s say, modern English poetry. This is also why whenever modern Greek poetry is translated into English (or into any other language, for that matter), it reaches comparatively easily—in contrast with the Greek poetry of past generations—an international audience.

So, the locations in the end of the volume have a more or less symbolic value. They are the landmarks of a trajectory, if you will. At the same time, they underline this feeling of not belonging somewhere. And, as I have lived in Mytilini (Lesbos) for the last five years, and before that in Chios, they are also, partly, a kind of ideological declaration: the fact that I consciously and deliberately decided to renounce life in big cities, like Paris, in favor of life in a small town, away from the center to the borderline of Europe.

I consciously and deliberately decided to renounce life in big cities, like Paris, in favor of life in a small town, away from the center to the borderline of Europe.

Goldwyn: You say that modern Greek poetry moves internationally with greater ease now than in generations past; that may be great for an international audience, but is something uniquely Greek lost in that? There is a price to translation and globalization, which is the erasure or alteration—perhaps some would even call it the deformation—of the local. In thinking about it now, that is as much a political question as a poetic one.

Ainalis: Whether we like it or not, we live in a globalized world—at least for the time being (because this may change sooner than we think). And our problems or concerns are global as well. Me, for instance, I feel that I can easily communicate with the literature of Japan or China. This would be inconceivable for a Greek author two generations ago. Certainly, there is a price to pay in globalization. Many local traditions, mentalities, ways of living all over the world have been trampled down violently during the last thirty years. Crucial social or communal knowledge is lost forever. Social and communal memory is being eradicated systematically, and this has been going on for decades now. And the heavy price that our generation will pay, indeed, will be the price of lost social or communal practices and knowledge, the loss of social memory. Soon enough we will be called to live in a lobotomized, constant present with absolutely no connection to the past (not even the events of our own past), with absolutely no openings to the future.

But, regarding literature, the question is somewhat different, because literature is a living organism with its own kind of memory and its own consciousness. The Latin word literatura originates etymologically from litera (the letter of the alphabet). And as long as there are some people out there capable of reading, they will always have access to the realm of literature, where nothing ever really dies. Of course, “oral literature” (what a contradiction in terms indeed!) is an altogether different question. But old literary works, written works, continue to live in the cognizance of younger authors. And thus, to answer to your question with an invocation taken from George R. R. Martins’s Song of Ice and Fire: “What is dead may never die, but rises again harder and stronger.”

Literature is a living organism with its own kind of memory and its own consciousness.

Mixed Media, 2018.

Goldwyn: If, as you note, “uprootedness” is a modern malaise, is a “rooting” or a “rerooting” possible? And, since it’s a poetry interview, is there a difference in the poetry of rootedness and the poetry of uprootedness?

Ainalis: As I said, when I talk about the past I am not talking about it out of nostalgia. No, I don’t think that a “rooting” or a “rerooting” is possible. One can’t “root” oneself if one doesn’t already have roots. Certainly, one can attempt it for the generations to come, but one can’t do it for oneself, mainly because this should be a collective and not an individualistic procedure. So, in my mind, the greatest modern poetry is a poetry of “uprootedness” in the sense that modern poetry is precisely the result of the poets’ vain attempt to fill the void of “not-belonging.”

Goldwyn: Speaking of loss and roots, I want to talk about Europe: France and Greece. You’ve lived in both, of course, and there has been a long tradition of francophilia in Greek letters. You yourself have translated much French poetry into Greek, particularly the prose poems of Baudelaire. Desert Monody represents your third effort at prose poetry (if I’m not mistaken), so could you tell us a little about what you got from translating Baudelaire, what prose poetry can do that poetry in verse can’t, and why you chose prose poetry for this volume?

Ainalis: I have often said that I strongly believe in the concept of “translatability” that Walter Benjamin develops in “The Task of the Translator.” In a sense, the role and the responsibility of a translator lies essentially in the understanding of the writer’s/poet’s era and, consequently, in the understanding of the writer’s or poet’s psyche. So every time that we translate someone else’s poetry and we understand—or we think that we understand—the essence of their poetry, the essence of this poet’s work, this alien essence becomes part of us, we carry it henceforth with us toward a new consciousness. But was this alien essence really alien in the first place, or had we already the psychological and sentimental predisposition to interpellate it?

I mean that already the choice to translate a certain poet states something (of course, I don’t speak here about translations made for a mere livelihood). Since my first poetry book, Electrography (2006), I was looking for various ways to incorporate narrative and dialogue (or monologue) in my poetry. I respect the historicity of literary genres and forms, but I prefer to see literature as a whole. I wanted—I still want—to combine the structural characteristics of the three great literary genres (poetry, narrative, drama) in a cohesive whole. Prose poetry is a great means of attempting exactly that.

April 2020

“There is also this civil war inside of me”

by Zisis Ainalis

for Christos Martinis

There is also this civil war inside of me

From which there is no retreat

From Mourgkana to Kassidiares a straight march

I signed off and surrendered my weapons

Fascists machine-gunned me on the barricades

Who gives a fuck about Leadership?

Ah, but there is a collaborator I’m hiding in my guts

Who will iron him out?

Who will soothe the child?

Who will drown the grief?

I am a sick bird

crawling

My wings are broken

Who stays awake by my bedside?

Who is washing my wounds?

Who stands a vertical crack in the wailing of memory?

And who shoos the birds

In the cold and scares them off?

There is also this civil war inside of me

Which constantly divides me.

Among the dark crossings and the mountain passes

My soul stands in the high places

(Alone in the cold

Beneath the dense pine forests

Swollen rivers)

Crawling like a snail piercing the darkness

In the motionless night,

Dragging its foot,

The horror, destitute, journeys on,

Devouring flesh.

Previously unpublished

Translated by Adam J. Goldwyn

Mixed Media, 2019.

Untitled

by Zisis Ainalis

Sometimes you stop in the white expanse. The hills are dusted with the sands of time and the moon is broken. Ruined desire stretches toward the horizon, the sad remains of a vanquished army, corpses countless worms jackals dogs—Hermanubis and St. Christopher howling beneath the ring of a bitten full moon that branches ominously toward the firmament. And then your magic stops time and cuts it with a vertical stroke. An oasis—maybe an optical illusion, you can’t tell—appears from nowhere. Lofty trees pure water green grass birds hidden secrets. On its lips millenarian words, and it hungrily breathes an old God. I turn around to see you. Desire is born again, the heavens open and the vision reigns. Man up and wait. I take hold of your hand and walk forward.

Opening poem from Desert Monody

Translated by Adam J. Goldwyn