The Tragic, the Absurd in Sadaa al-Daas’s “Zoo Syndrome”

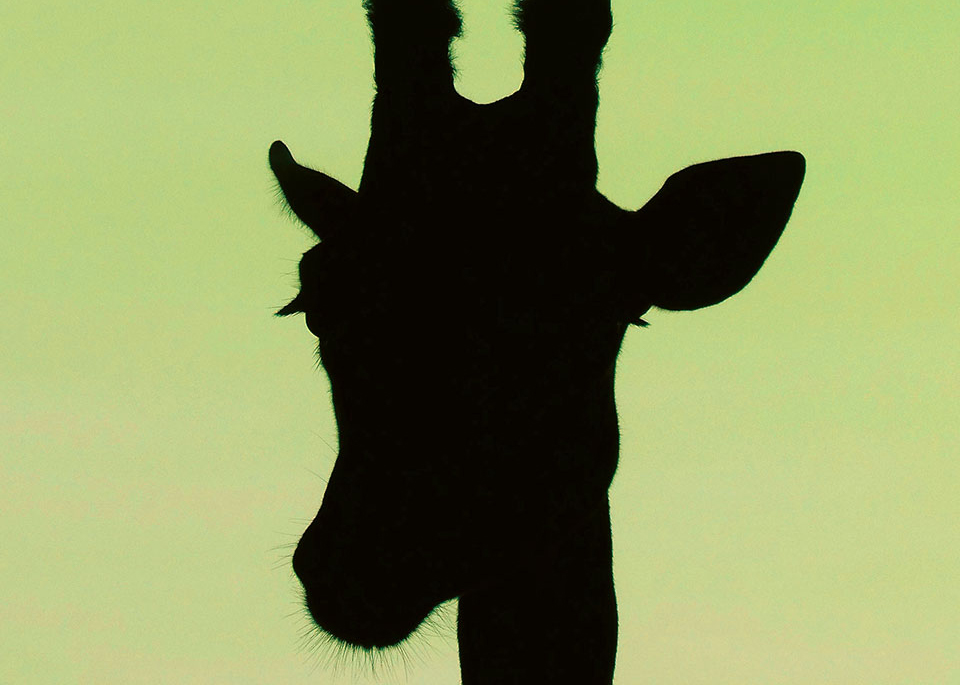

ONE MORNING, WHILE READING his newspaper, the narrator of Sadaa al-Daas’s “Zoo Syndrome” looks up to find his wife changed into a prancing doe. His neighbor is a lamb (pretending to be a lion). His boss is a bootlicking anteater. His coworkers are ravenous rats. And the world’s political actors are lions and tigers. Having accepted his Kafkaesque existence within a giant zoo replete with tragicomic symbolism, he recalls how these metamorphoses first came about.

Like many of her other works, al-Daas’s “Zoo Syndrome” allegorizes global apathy and individual powerlessness in the face of ongoing disaster. As it collapses the literal and the metaphorical, the story reveals the artificiality of separation between the real and the absurd. Was the world any less farcical before the onset of the Zoo Syndrome? The zoo simply makes clearer the narrator’s frustrations in the human world.

Yet even as he accepts his new reality, al-Daas’s narrator seems to insist on seeing his experience as a temporary encounter with the allegorical, hoping perhaps to find meaning in the absurd. His language betrays a yearning for the human beneath the animal—people present as, or take the form of, this or that animal, but they are people still (he hopes). His surroundings are disguised, but he still knows what lies beneath. Still, in the seamless onset of the zoo syndrome and in the narrator’s readiness to go about his life (even as he questions his sanity), we see an existential resignation to an animalistic world order. The workers he meets bray or cluck or bark. His wife quickly becomes his doe. The extent of his power lies in meaningless online posts, and the tragedy of his situation is, above all, his inability to resist it despite having seen the world more clearly than before.

In his account, the comic family dynamics of the anthropomorphized giraffe and rhinoceros having lunch, or of the dog-policemen hounding a cat for a permit, verge on the grotesque in their startlingly accurate portrayals of everyday helplessness. In my English afterlife of the story, I tried to straddle the tragic and the absurd. As I think about the process of capturing the slippages between the text’s moods, I think about the spaces of translation.

The first draft came about during a cold Amman winter, at an uncomfortable granite kitchen counter, against a backdrop of consistently somber and serious news coverage in Arabic (English-language media, or so that space reminded me, took up the hour with banter that left little room for the unpleasantness of war coverage). A few months later, I returned to the work during a warm Montreal spring. Reading the English lines brought back memories of the Arabic ones, which in turn spoke back to me in a different, competing English.

My space was my co-translator. The Amman drafts, I think, reflected a closeness—linguistic, cultural, emotional—to the imagined setting of the text that made it harder for me to fully indulge in its restraining of the absurd to greater effect. These drafts were done too close to home. But in the other home, in Montreal, the text became less rigid, challenging me to accept the narrator’s resignation and to allow the universalism of the story’s animalistic imagery to emerge unhindered or anchored to a particular geopolitical context. In the end, I drew from both afterlives and from both spaces. And I now think back to all the rooms and cities that have translated with me.

Editorial note: Read “Zoo Syndrome” from this same issue.