Dancing Wisdom and Embodied Knowledge in African Diaspora Traditions: In Conversation with Yvonne Daniel

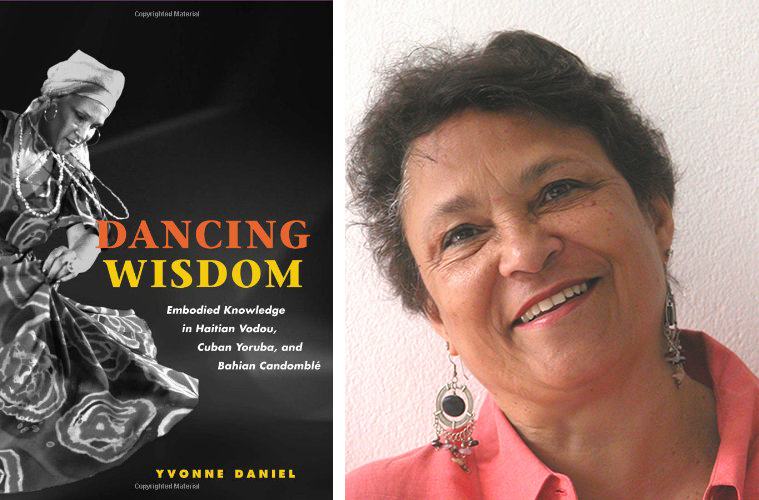

In her landmark interdisciplinary study of African diaspora religious systems through dance performances, Yvonne Daniel considers three religious systems that rely heavily on dance behavior—Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba (commonly called Santería), and Bahian Candomblé. Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomblé offers the rare opportunity to see into the world of mystical spiritual belief as articulated and manifested in ritual dance.

I came across Yvonne’s work while researching a documentary film on the subject and interviewed her during the course of research.

Vikram Zutshi: What is the premise of embodied wisdom? How did you find your way to this field?

Yvonne Daniel: The premise of my book, Dancing Wisdom, is that within the dancing body there is wisdom to be gained. From library investigations, years of field research across the Caribbean and in Afro-Latin mainland territories, as well as from personal dance experiences, I have derived great understanding of what African descendants in the Americas have passed on through generations, especially those in ritual communities of Cuba, Brazil, and Haiti. My book is an effort to introduce African history and sacred customs to an audience that, until recently, has mainly heard of African religious traditions as superstitious beliefs or maligned behaviors. I use the results of “observant participation” in African diaspora dance and music traditions to show the commonalities and distinctions within related ritual communities but more so to reveal the importance of African spirituality in the Americas and the beauty of African diaspora dance/music traditions. I found my way into the field of dance anthropology through its main foremother, Katherine Dunham, an African American dancer-choreographer-anthropologist-activist who, in the late 1930s to the mid-1960s, also examined Caribbean dance/music practices for both aesthetic and cultural knowledge, which she made visible in stage and film performances.

Both public and private ceremonial practices reach for healing and health, bonding and goodwill, and deepening connections to nature and a spiritual universe.

Zutshi: What are the commonalities in the dance traditions of Africa, Brazil, Cuba, and Haiti, and how do they relate to Yoruba and Vodun/Vodou cosmologies?

Daniel: The major commonalities within the dance/music traditions I study are:

(a) A conviction that dance/music ceremonies bring ancestral and spiritual wisdom to the present or to contemporary communities;

(b) The dancing body is the vehicle of transcendence; human voices in chants and songs and ancient rhythmic sequences played primarily with human hands from within a battery of drums and other percussion instruments both initiate a codified dance vocabulary with the dancing body that is passed on through succeeding generations and across geographic space;

(c) The ritual family and the ritual space are at the core of set liturgical orders; in repetitive celebrations, family needs and relationships produce an annual series of dance/music ceremonies—some public, some private;

(d) Both public and private ceremonial practices reach for healing and health, bonding and goodwill, and deepening connections to nature and a spiritual universe;

(e) And most importantly, none of the ceremonial practices I have witnessed or participated in, since I began in 1970 or so, have ever involved sexual or vulgar dimensions—that is a major commonality, although disputed in many newspaper and social media reports over the years. The dance/music ceremonies find their origins in both Central and West Africa (e.g., Angola, the Congos, Cameroon, Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, etc.), where several distinct belief systems (some called Kongo, Mbundu, Orisa, Vodun, etc.) combined through marriage or conquest over time but mainly were associated with lands and the peoples on them that were guarded by family spirits. Additionally, some individuals were sometimes called to worship particular spirits.[1]

In the diaspora, African belief systems were transformed but continued as Vodou in Haiti, including Rada and Petwo or Congo rites and Candomblé in Brazil, including Angola, Jeje, and Ketu/Nago rites. In Cuba, the varied rites are separated as distinct belief systems or religions called Palo, Arará, Lukumí (or Santería or Yoruba), and Carabalí (or Abakuá). (In Dancing Wisdom, I used “Yoruba” in my title because that is what was in use at the time of my original fieldwork and that was what the dance/music was called, instead of Lukumí or Santería. Also, I limited my study to “Bahia,” not all of Brazil, since Brazil is tremendously large and I only concentrated on Bahia city in Salvador da Bahia state.)

Zutshi: What are your thoughts on spirit possession and mediumship in African diaspora culture, including dance? How does the body become a vessel for extradimensional entities?

Daniel: You can find some spirit possession, trance, and mediumship in most of the diaspora belief systems discussed here; however, I think these words are too closely aligned with pejorative descriptions and shallow understandings of African-descendant cultures. The ritual performers in my studies also use these terms, but I am convinced that they have been inundated with anthropologists and other research specialists since the colonial era and now often repeat what they have heard or read about themselves. Since I look primarily at dancing bodies, I use their other terms, “manifesting spirit,” “transformation,” or “transcendence” into an altered state. Regardless of which term is used, they all suggest the presence of a spiritual essence or being that uses the human body or the dancing worshipper to communicate to others. The process of accomplishing this is a learned experience or bodily experience within ritual instruction, culminating in formal initiation. Such instructions are omitted when the divine spirits are insistent and will not wait for initiation. This is considered unadvisable by knowledgeable ritual leaders. (Chapter 2 of Dancing Wisdom is dedicated to the approximation of this dance feat or the complexities of this process through dance analysis, body figures, and a series of charts.)

Regardless of which term is used, they all suggest the presence of a spiritual essence or being that uses the human body or the dancing worshipper to communicate to others.

Zutshi: To what degree does Catholicism clash and/or merge with African religion and culture?

Daniel: Catholicism came to the Americas first with Spanish colonials but also with Africans from the Kongo Kingdom in what was called Angola or West Central Africa. Many Central African groups were exposed and converted to Catholicism since the fifteenth century, and these were the first and most numerous enslaved peoples to come to the Americas up through the seventeenth century. So, already and for most of four centuries (until the official end of slavery in 1888), there was a meshing of Catholicism and African religious practices as the transatlantic trade in Africans evolved. (For details, see note 1.) The parallel structure of the Catholic saints and African divinities (called Lwas, Orixás, Orichas, etc.) has impacted religious practices in the diaspora as a way of publicly or outwardly giving reverence to African divinities, especially when Africans were prohibited from their own worship practices. Some Catholic practices are pronounced in African diaspora practices, as in the Catholic lithographs on Haitian Vodou altars or in the requirements of a Catholic mass or presence of a Catholic priest at certain Lukumí or Candomblé ceremonies.

Still, the Catholic and African belief systems remain distinct; only the African systems are based in a dance/music liturgy, spirit manifestation, and divining systems. In African practices, individuals are transformed into ritual family members through affiliation and service over time and through accumulation of plant and animal, music and dance, history and spiritual knowledges. All culminate in initiation so that ritual members can receive or give counsel from the manifested divinities within dancing human bodies. Ritual members maintain strong connections to nature and the world of plants and animals; their practice is more a way of living rather than sets of religious dos and don’ts.

Zutshi: How are the body, mind, and self conceived in Yoruba, Candomblé, and Vodou cosmologies? How do these differ with Western psychoanalytic theory?

Daniel: There have been several researchers who have used psychoanalysis as the base for examining Vodou and Lukumí (often called Santería in these texts) in hospital, medical, and legal settings, but I am an anthropologist who examines people, cultures, and societies—not individuals and psychological issues generally. I have had to deal with a measure of psychology as my field consultants spoke in psychological terms about their dance experiences. I have regarded these discussions of emotions, the self, and its “transformations” within dance and movement analyses. I do find Maya Deren’s psychological perspective and intimate experiences in Haiti “familiar,” as these are like my own dancing experiences in Haiti, Cuba, and Bahia, Brazil.

Your basic question here, however, is how do these systems differ. I would say that the differences are subtle but important. To most viewers or visitors to public or private ceremonies, many diaspora ceremonies probably appear similar, if not the same, with the main difference in languages used: Haitian Creole, Spanish, or Portuguese with varied archaic forms of Kikongo, Yoruba, and other African languages in the vocal music, especially. While the Lwas, Orixás, and Orichas are generally considered part of the ritual family, most of the Haitian lwas are perceived as family spirits, and most of the Brazilian Orixás and Cuban Orichas are perceived as cosmological spirits. While all the systems are connected intimately with nature, the Kongo, Congo, and Angola rites connect more directly to nature, to simple ritual structures, and unadorned material items. On the other hand, the Yoruba, Ketu, and Nago rites are unabashedly complex, with a preference for hierarchy and elaboration. They all differ from European and North American beliefs in that they view almost everything in terms of the extended spiritual family, with the individual able to construct and manage her/his relationships to the divinities through sacrifices, food offerings, and dance/music ceremonies.

April 2017

Yvonne Daniel is professor of dance and Afro-American studies at Smith College in Massachusetts and the author of Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomblé, a landmark interdisciplinary study of African diaspora religious systems through their dance performances.

Yvonne Daniel is professor of dance and Afro-American studies at Smith College in Massachusetts and the author of Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomblé, a landmark interdisciplinary study of African diaspora religious systems through their dance performances.

Footnotes

[1] For documented history, see John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800; Linda M. Heywood, ed., Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora; and James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World 1441–1770.